We are landing this plane, softly.

The past three years have been miserable. And we are coming out of the clouds. The soft landing is getting real. Nothing is guaranteed, but wow, we could pull this off.

We are coming out of 2023 better than most expected. I am not surprised, but this time last year was rough. I explained how we got here in my recent interview with the Financial Times. 2024 is on track to be even better.

Claudia Sahm is, perhaps to her chagrin, best known for creating the eponymous Sahm rule, a recession marker developed as part of a discussion of economic stabilisation payments to individuals. She is almost as well known for taking a contrarian view of the policy response to the coronavirus pandemic. She argued early on that the bulk of the post-pandemic inflation was driven by supply constraints that would pass, and urged policymakers not to overreact. Below she offers views on whether the inflation fight is won, productivity, consumer sentiment, the Phillips curve and much else.

Inflation was Covid and Putin, and it was transitory.

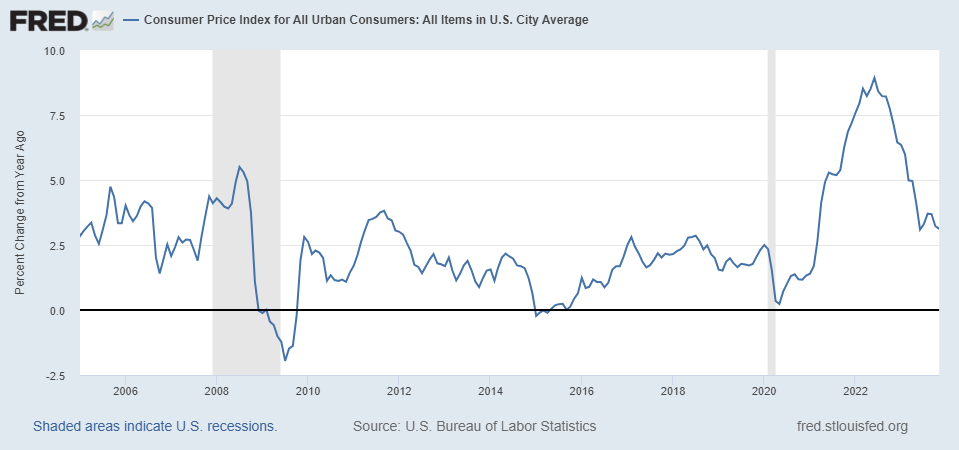

We shut a $20+ trillion U.S. economy down in March 2020 to protect us from a deadly pandemic. Millions of people lost their jobs by the week. The pandemic was global, so the economic disruptions in supply chains went far beyond our shores. Covid came in large waves throughout 2020 and 2021 before the vaccine was available. Then Putin invaded Ukraine in early 2022. Reopening the economy, getting workers and goods back, and navigating a war in Europe turned out to be harder and slower than I had expected. In 2023, we saw that inflation was indeed transitory but lasted for two years, not one. That extra year meant more hardship for many, but it is coming down without a recession. Remember that having no paycheck and no raise is worse than higher prices.

Sahm: I have not, and do not now, subscribe to the view that the inflation we have been living through since 2021 is primarily demand-driven, like Larry Summers and my friend Jason Furman did. Those folks thought we put too much money into people’s pockets and there was too much pent-up demand. If you were in that camp, you thought we needed to jack up rates and see wage growth come down.

… I look at inflation and say that’s because of disruptions from Covid and the war in Ukraine. And because those will eventually work out in some way, inflation will come down. That leads to very different policy prescriptions to fight inflation. And it leads to very different views on the things like whether the $1.9tn American Rescue Plan was a good idea; or whether waiting to raise rates was a good idea. If it’s all demand, then you’ve got to destroy demand. But I don’t think it’s all demand.

And encouragingly (and unexpectedly), Larry Summers, whose Financial Times interview was last Friday, acknowledges what others have said for some time:

I get it. In 2022, the impossible was possible, as I argued. In 2023, it happened. Forecasting is tough, and good economists follow the data. I am just happy, we all should be, that 2023 happened.

Also, one thing I did not go through in the interview is how the Covid and Ukraine disruptions allowed businesses to raise prices more than their rising costs would typically have justified. Isabella Weber and Sam Rines’ work here is important.

Helping people helps people.

I am proud to have gone to bat for the American Rescue Plan with data, research, and common sense. It did an incredible amount of good. I know people are angry now, and some very prominent macroeconomists blame it for the high inflation. Wrong. It helped kick start the strong recovery in jobs and wages and included various social programs like the new Child Tax Credit, which had no work requirements.

I have written extensively about the Rescue Plan.

The inglorious Phillips curve.

I have made it abundantly clear on every platform that the Phillips curve was not the right tool for this time. The policy guidance from people using it would have been disastrous if followed. We did not “need” a recession to get inflation down. Inflation fell from 8.9% last year to 3.1% in November. And unemployment stayed below 4%.

That was not supposed to happen. It did. I called it, as did others who saw the Covid disruptions and the war in Ukraine. If you missed that and saw inflation as demand-driven, you end up incorrectly with the Phillips curve. Me again in the FT:

Sahm: This fundamentally goes back to a view about how much of inflation is demand versus supply. If you think it’s demand-driven inflation, you can fight that with the Fed’s tools. But how do you know how much monetary tightening to do, how much unemployment you need to get inflation down? So then you march off to the Phillips curve. There are more sophisticated versions of the Phillips curve that incorporate supply shocks. No one brought those out. The versions of the Phillips curve that were brought out in policymaking circles went back to the 1950s or 1960s — essentially just inflation versus unemployment.

The Phillips curve was used by the same people denouncing the American Rescue Plan to make statements like, “We need five years of 6 per cent unemployment.” But it goes back to why did inflation spike, demand or supply? It’s clear now who was right: it was largely supply. It was completely valid to argue in 2021 that when inflation took off, it was demand. The American Rescue Plan was big, it came after two very big fiscal relief packages and the Fed had been adamant about not raising rates. But the fact this year that inflation has notably come down and unemployment has stayed low only happens if it was mostly supply-driven.

Paul Krugman asked me last year what I would suggest if not the Phillips curve. I said we should start with common sense.

As it turns out, Larry Summers has changed his tune.

So it certainly hasn’t been a glorious period for the Phillips curve theory in any of its forms. But I’m not sure we have a satisfactory alternative theory. The theory to which many economists are gravitating to is that the Phillips curve is basically flat, inflation is set by inflation expectations, and inflation expectations are set by the people who form inflation expectations. And that’s a little bit like the theory that the planets go around the universe because of the orbital force. It’s kind of a naming theory rather than an actual theory. So I think inflation theory is in very substantial disarray, both because of the Phillips curve problems and because we don’t have a hugely convincing successor to monetarist-type theory.

Again, common sense, Larry. Also, the Phillips curve is vertical at the moment.

Landing that plane.

We have not landed the plane softly yet, but we will next year. My definition of a soft landing is 2% inflation (or within spitting distance and unemployment around 4% (preferably below). We can see the runway. And it’s clear from last week’s Fed press conference that Jay Powell can, too.

Macroeconomists will debate for decades how we pulled off the impossible. The Fed had next to nothing to do with this cycle, but what is important now is that we land this plane and get to the other side. The past three years have been traumatic, and we need time to heal.

In closing.

The soft landing is in sight. 2024 should be the year when we get back to some semblance of normal. We deserve it.

Thank you for being the only economist outside of the MMT community who knew inflation was a supply issue, proved it with facts and pushed back against those who wanted to blame it on the spending. This is greatly appreciated.

You got that right. He told Obama to side with the banks and to flip a fish (too-small stimulus package) to the public, prolonging a recession that hurt millions of Americans. It’s galling to watch Jaimie Diamond self-appoint himself as a spokesperson for income inequality. These people have no conscience.