Price-price spirals take us for a spin

Macroeconomists fiercely debate the causes of inflation now and how policymakers should respond. Profits as a driver of inflation is an especially contentious claim.

Last week we learned that consumer price inflation, while still somewhat elevated, is coming down. At the same time, unemployment is holding steady at its fifty-year low. The sources of inflation during the past few years and its path going forward are debatable, as are the best policy responses. In a recent interview, I was asked how much profits are contributing to inflation. “It’s complicated,” was my reply.

When inflation picked up in 2021, some economists turned to the Phillips Curve—with its tradeoff between unemployment and inflation— to argue that we “needed” a recession to bring inflation down. Others like myself countered that disruptions in supply chains, labor shortages, and the war in Ukraine had to resolve before inflation would come down. Finally, a group of economists led by Isabella Weber, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, said that profit-seeking was the key contributor. Reality likely reflects all three hypotheses, and the degree is crucial for policy advice. If the first group is correct, the Fed can go it alone. If Weber and I are, Congress and other policymakers outside the Fed must act up too.

Today’s post sketches out the basic arguments behind a price-price spiral, or, as Weber calls it, sellers’ inflation. For a thorough discussion of the concept, see Weber and Wasner (2023) and Weber and coauthors (2022). Lindsay Owens, Executive Director at Groundwork Collaborative, and her colleagues are also very active in the profit discussions. Also, watch Owen’s excellent interview with Jon Stewart.

What is the price-price spiral?

It’s a bit complicated. Only in the past few years did the role of profits for inflation get broader interest, and its proponents have brought varying terminology. But that’s not to say the ideas are new. Isabella Weber is one whose research predates the pandemic. Here’s how she describes the sellers’ inflation:

We argue that the US COVID-19 inflation is predominantly a sellers’ inflation that derives from microeconomic origins, namely the ability of firms with market power to hike prices. Such firms are price makers, but they only engage in price hikes if they expect their competitors to do the same. This requires an implicit agreement which can be coordinated by sector-wide cost shocks and supply bottlenecks. ... Rising prices in systemically significant upstream sectors due to commodity market dynamics or bottlenecks create windfall profits and provide an impulse for further price hikes.

Note how the interaction between the bargaining power of firms and a crisis like the pandemic presents an opportunity to raise prices aggressively. Outside of a crisis, firms cannot exploit this advantage. This excellent podcast with Weber offers an accessible discussion of the role of profits in inflation. I highly recommend it.

More agnostic as to why, then-Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard, in October 2022, drew attention to the fact that profit margins had increased notably, reflecting the fact that consumer price inflation was much higher than producer inflation, even as the latter was elevated due to disruptions from Covid and the war in Ukraine:

Since the pandemic, significant supply and demand imbalances have coincided with large increases in retail trade margins in several sectors. In some sectors, the increase in the retail trade margin exceeds the contemporaneous increase in wages paid to the workers engaged in retail trade, although this is not true in food and apparel. The return of retail margins to more normal levels could meaningfully help reduce inflationary pressures in some consumer goods, considering that gross retail margins are about 30 percent of total sales dollars overall.

Importantly, Brainard highlighted a path to lower inflation that did not consist entirely of the Fed stomping demand. While it is too early to tell how important this (or any) channel is for inflation, recent disinflation is encouraging and consistent, with profit margins narrowing and easing the pressure on inflation.

What’s the real-world evidence for it?

Reality played a role in bringing attention to price-price spirals. It might not fit neatly in our ‘standard models’ and was initially attacked as “very stupid.” But the evidence is piling up that it should receive serious consideration. Inflation reached its highest level in forty years, as well as an all-time high in profit margins:

Even so, one could look at these margins—as some Fed officials other than Brainard have—and say it simply reflects too much demand, and demand should be reduced with higher interest rates. That’s the indirect way that profit margins narrow. But that logic gives firms a pass and ignores the special circumstances of the Covid crisis that could go beyond simple supply and demand. And again, as Weber notes in her research, crises are central to opening the door to sellers’ inflation. The pandemic and war in Ukraine did, and Sam Rines, managing director at Corbu, offers an example:

Pepsi found [after the invasion of Ukraine] that even though they had about 4% of their revenue exposure to Russia, they could push price everywhere else and make up for that volume without any problem …

[Why don’t others compete on price to get more market share?] Because they can raise price right alongside of them and have those have those larger margins. I mean, it's one of those things with Pepsi, right? Pepsi, Coca-Cola. You shouldn't have Pepsi being able to push price, in theory, right? It should be Pepsi and Coca-Cola battle it out and you have very minimal price increases and they don't have the ability to really play catch up with inflation. And that's simply not the case right now. They're just willing to take it…

A lot of companies had these one-off or very, very rare excuses to raise prices and begin to find how much the consumer would take.

While not a slam dunk, what firms say in earnings calls and do in the real world is consistent with a price-price spiral and strategically using the crisis to profit. Strong demand is part of the story, but it’s hard to deny that there isn’t more to it. The market power of firms and incentives to enrich shareholders interacted with imbalances caused by Covid, and the war led to profits driving inflation. And it’s not a few isolated cases. Earnings calls have been filled with CEOs telling shareholders about opportunistic price increases. Groundwork Collaborative has helpfully compiled those calls, and the practices are widespread.

What does it all mean for us today?

Price-price spirals turn conventional policy advice about inflation on its head. The Fed should not go it alone; it should calm down some because it can’t fix profit-driven inflation. At the same time, it could needlessly weaken the economy and cause a recession. Fiscal policymakers have a crucial role in the fight against inflation.

Price controls.

Early in 2022, Weber kicked off the contentious debate about price controls as a way to fight high inflation. Here’s part of her piece in the Guardian:

Today, there is once more a choice between tolerating the ongoing explosion of profits that drives up prices or tailored controls on carefully selected prices. Price controls would buy time to deal with bottlenecks that will continue as long as the pandemic prevails. Strategic price controls could also contribute to the monetary stability needed to mobilize public investments towards economic resilience, climate change mitigation and carbon-neutrality. The cost of waiting for inflation to go away is high.

What sounds like a radical idea was later adopted in (not-so-radical) Germany to deal with the crisis levels of natural gas prices due to the war in Ukraine. Weber served on the official committee which proposed a ‘Gas Brake’ to the government. There were price caps for households up to the amount related to their prior year’s consumption. Above that, gas use was charged at the market rate. In addition, there was a financial incentive to consume less gas. It was a modern-day version of price caps with a mix of carrots and sticks to contain usage.

Taxing extraordinary profits.

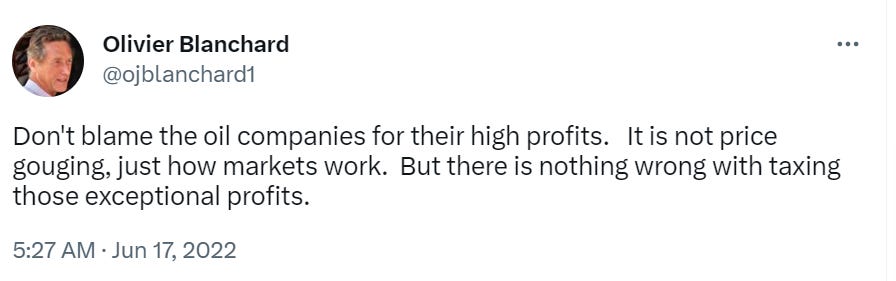

A somewhat more conventional, though also contentious, approach to reining in inflation during crises is a tax on extraordinary profits, also known as windfall taxes. It shifts extra profits from shareholders to taxpayers during a crisis, such as the profits to energy firms due to the war in Ukraine or shipping companies due to the global pandemic. Olivier Blanchard raised the idea last summer.

A concern with the approach among many economists is that the tax could create disincentives for firms to invest in the supply of their goods or services in the future, so while it might limit current price inflation—no reason to raise prices aggressively and risk losing customers, if the profits don’t go shareholders—it risks creating future inflation due to reduced supply. However, the extraordinary tax can be designed to limit those disincentives. Above all, the taxes must be temporary and tied to the crisis, not business as usual. Practically, only countries where the firm is located can pursue this policy. Germany has no natural gas producers, so it was not an option, though they did tax other domestic energy producers profiting from high energy prices. As with price controls, the record is mixed with the design.

Reduce supply imbalances.

Finally, a way to address the high profits and the related inflation is to lessen the crisis that gave rise to them. Supply-side disruptions drove up firms’ costs and limited the supply, giving them a reason to raise prices. But some also used it as an opportunity to raise prices even further. Again, without weighing in how much of a role extra demand plays, Congress and the White House can take steps to help raise supply and ease price pressures. Here is a White House action to reduce high oil prices, which is similar to a plan that Skanda Amarnath and colleagues at Employ America advanced:

the Administration intends to repurchase crude oil for the SPR when prices are at or below about $67-$72 per barrel, adding to global demand when prices are around that range. As part of its commitment to ensure replenishment of the SPR, the DOE is finalizing a rule that will allow it to enter fixed price contracts through a competitive bid process for product delivered at a future date. This repurchase approach will protect taxpayers and help create certainty around future demand for crude oil. That will encourage firms to invest in production right now, helping to improve U.S. energy security and bring down energy prices that have been driven up by Putin’s war in Ukraine.

As in this example, it’s important to recognize the role of Congress and the White House in fighting inflation, especially in times of crisis. The Fed cannot drill oil, produce cars and semiconductors, or bring back workers; Congress and the White House can and are doing so. In addition to the contracts with oil producers, increased legal immigration and energy and semiconductor investments in the Inflation Reduction Act and Chips Act fight current and future inflation.

In closing.

The debate over the causes of inflation is an important one.

Misdiagnosing the problem leads to bad medicine. And bad medicine is harmful now and in the future. There is mounting evidence that the price-price spiral is real, especially during a crisis, and it’s time for us to grapple seriously and professionally with that reality. We don’t know the answers about the recent high inflation, and while it might never be settled, it’s worth our best efforts to understand.

We need more macro economists like you that support isabella weber calling out sellers inflation. With that being said, inflation is a complicated dilemma with many factors (including the fed rate hikes) being involved. It's also important to recognize the importance of congress and yes they certainly are capable of doing more but with DC being so divided and a 2024 presidential election coming up I don't see it happening. Inflation is on the way down but we've got work to do still. The labor market has been resilient as I've said before, the Phillips curve is no more and there is no need to attack the middle class just to get down inflation. They deserve better.

Great post. I was thinking about Jeffery Sachs' idea that the economy is controlled by W.H.O.M. WHOM rules America, so to speak .Wallstreet, Health care companies Oil companies and the Military Industrial Complex. Maybe WHOM kick started inflation ,a WHOM- price spiral. Also the wage -price spiral no longer happens because we shipped so much production to Asia and destroyed unions in the private sector.