Sahm-thing more on the Sahm rule

The rise in the unemployment rate has raised concerns about the possibility of a recession, but the story is not as simple as the usual rules of thumb.

The economic narrative and what the Fed should do are in a near-daily tug-of-war. Signs of cooling in the labor market are of particular concern, and the Sahm rule, the recession indicator based on changes in the unemployment rate I developed, is getting attention. Today’s post shares a new analysis of what might be happening ‘under the hood’ of the Sahm rule.

High-level takeaways:

A recession is not imminent, even though the Sahm rule is close to triggering.

The Sahm rule is likely overstating the labor market's weakening due to unusual shifts in labor supply caused by the pandemic and immigration.

The risk of a substantial weakening or a recession in the next several months is elevated, adding to the case for the Fed to begin cutting rates.

My Fox Business interview is a good summary. The other guest, Michael Kantrowitz at Piper Sandler, also makes excellent points on his and other recession indicators.

Monitoring the labor market is always important. The unusual features of the pandemic-driven cycle challenge the standard relationships, like the Sahm rule, though we should be wary of completely disregarding them.

A gradual rise in unemployment is no reason to relax.

It’s tempting to see the slow rise in the unemployment rate during the past year as setting it apart from earlier recessions:

“It’s ahistorical what we’re observing,” Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee told reporters last week. “You don’t see gradual increases in the unemployment rate [like this]. … It looks so different than a normal business cycle deterioration that it doesn’t feel like the beginning of a recession.”

The rise in the unemployment rate has indeed been gradual. The three-month average (orange line) was 4% in June 2024, relative to the three-month low of 3.5% in April 2023—a 1/2 percentage point increase in 14 months.

Contrary to Goolsbee, that slow rise is not unusual with the beginning of a recession and is not a reason to downplay the risks of a recession. The unemployment rate tends to increase gradually in the lead-up to and early months of the recession. Then, it picks up steam and often peaks after the official recession ends. This is the dynamic behind the Sahm rule as a recession indicator.

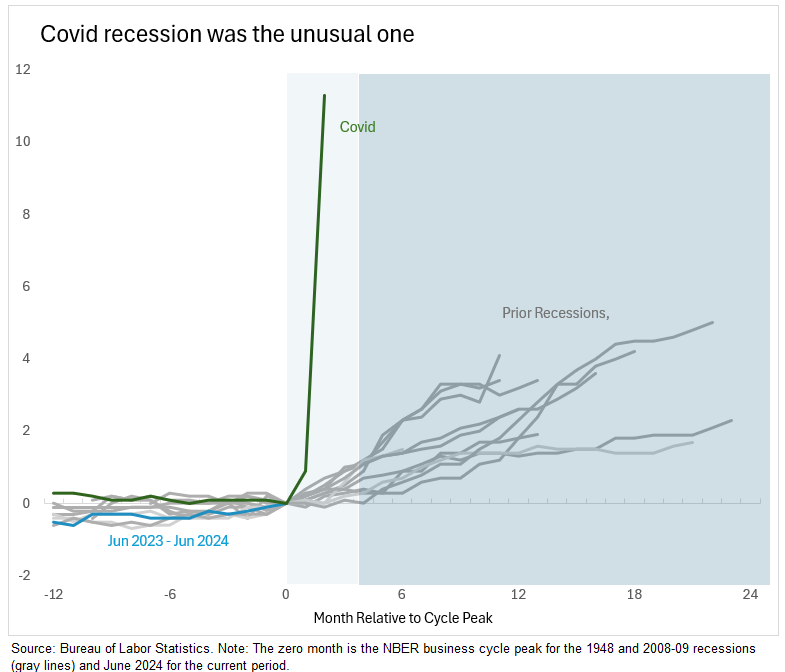

The gray lines in the chart below show the change in the unemployment rate in the 1948 to 2008-09 recessions. The changes are relative to the month the recession began (the NBER business cycle peak) or the zero month. The white area is the 12 months before the recession began, the light-blue area is the first three months after it began, and the darker blue area is four months to two years after it began.

On average, the unemployment rate peaked three percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. However, three months in, the average rise was only 0.5 percentage point, and the average increase in the three months prior was 0.1 percentage point.

The darker blue line shows the change in the unemployment rate in the past year, with June 2024 as the zero month. The current rise is not particularly gradual relative to past recessions. If the unemployment rate continues to rise and triggers the Sahm rule at 0.50 percentage point or more, it would align with other early-stage recessions.

It’s a fast, not slow, increase in the unemployment rate that would be unusual early in a recession. Regarding speed and magnitude, the Covid recession (green line) was ‘off the charts.’

The Covid recession is not the comparison now, but we should not forget how massive and disruptive the pandemic was for the economy. It is four years later, but echoes remain, making it more difficult to interpret the economy.

The rise in the unemployment rate is not as ominous as it would normally seem.

The gradual pace of the current rise in the unemployment rate is not unusual, but some underlying drivers are making the current reading of the Sahm rule look overly ominous. The Sahm rule was 0.43 in June 2024, close to the historical trigger of 0.50 in past recessions. One more increase in the unemployment rate in July to 4.2% would trigger the rule, suggesting that we are in the early months of a recession.

That would almost certainly be wrong. A recession is a “significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy,” it’s hard to see the signs broadly now. As Ernie Tedeschi shows, the economic indicators that the NBER uses to make that determination, such as consumer spending, personal income, and payroll employment, are growing at or above trend, not near contracting.

What is the Sahm rule using the unemployment rate missing now? Dramatic shifts in the labor force, including the plunge in participation early in the pandemic and then the jump in immigration in recent years, are likely affecting the change in the unemployment rate in a way that would not be typical in prior business cycles.1

The Sahm rule uses the change in the unemployment rate to identify a recession. At the same time, there are changes ‘under the hood’ in the composition of the unemployed that are similar across recessions. However, the recent shift in the composition is not typical for a recession or, at least, not for an imminent recession.

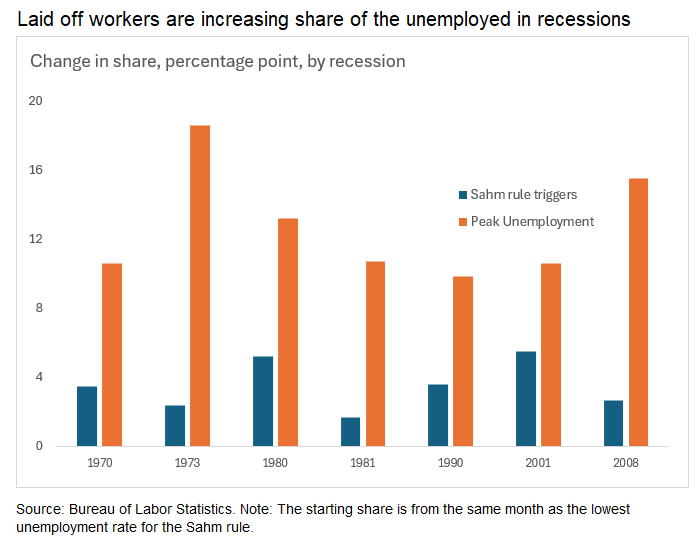

Let’s consider three main groups of unemployed people: 1) those who were laid off, 2) those who left their jobs, or 3) those who entered the labor force. In past recessions, the share of unemployed persons laid off had risen by 3.5 percentage points on average when the unemployment rate rose by 1/2 percentage point, and the Sahm rule triggered (blue bars); it continued to rise considerably until the unemployment rate peaked (orange bars).2

Currently, the share of laid-off workers among the unemployed (yellow bar) is only two percentage points higher than a year ago. While that’s below the average when the Sahm rule triggered in past recessions, it is not a striking outlier regarding cyclical weakening, especially considering the Sahm rule is below the trigger.

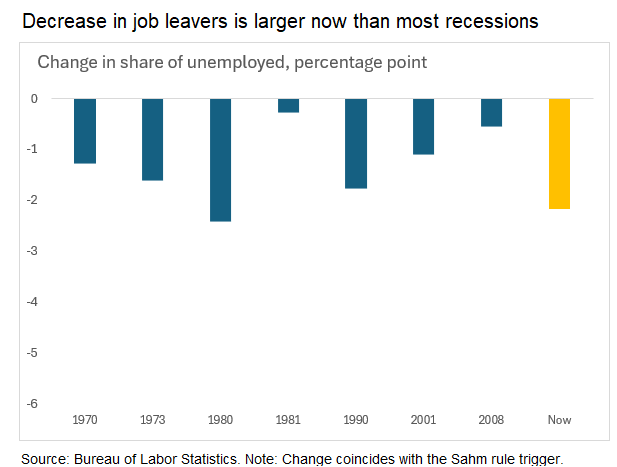

The share of job leavers among the unemployed decreases with recessions (below) since weakening labor demand discourages workers from voluntarily leaving jobs without a new one lined up. However, the share of job leavers among the unemployed in the past year dropped almost twice the average in past recessions. The swing likely owes to weakening demand now and extraordinarily strong demand during the labor shortages in recent years.

The recent changes in the shares of laid-off workers and job leavers among the unemployed broadly resemble those seen in the early stages of past recessions. That is not the case for the third group: entrants to the labor force. In past recessions, the share of entrants—those without work history or those returning to the labor force—fell. The weakening in the labor market discourages them from looking for work. Currently, the entrant’s share is unchanged. That would be consistent with increased labor supply from immigrants pushing up unemployment and not a sign of weakening demand as is typical in a recession.

That divergence in the behavior of entrants is sufficient reason to be cautious when interpreting the Sahm rule. Even so, it is not a reason to discount the signal entirely. The rise in laid-off workers and the decline in job leavers are consistent with the weakening of the labor market. One could view the current Sahm rule reading of 0.4 as something closer to 0.3 in normal times.3 Following what’s happening below the surface is best.

“No imminent recession” isn’t good enough.

The Sahm rule is a recession indicator, not a recession forecast. Applied to historical data, as it was available in real-time, it has been triggered early in every recession since 1970. It had only two false positives since 1959—when the rule hit 0.50 or more, but the economy was not a recession.

If we look back to the two historical false positives, they were soon followed by a recession. The Sahm rule triggered in December 1959, but the recession began in April 1960. Similarly, it triggered in October 1969, and the recession began in December 1969. Those two were wrong on the timing but right on a recession.

On the other hand, this might not turn into anything. Some close calls for the Sahm rule have turned out fine. Such as 0.47 in November 1967 (blue line). It turned back down, and there was no recession. Notice that revisions (red line) to the seasonal patterns in the unemployment rate since then washed much of that peak in 1967. (The revisions also softened the Sahm rule last fall.)

Two other such close calls have occurred in the real-time Sahm rule since 1970: November 1976 at 0.50 (which, when unrounded, does not trigger) and July 2003 at 0.47. It is still possible that it does not trigger in the coming months. That would be consistent with hiring catching up with the new supply of workers and the unemployment rate flattening out as we move further from the time of labor shortages.

In closing.

The Sahm rule is a number. The change in the unemployment rate is more than a number; it’s the changing circumstances of millions of people, and the changes are especially complicated now, as Jeanne Whalen describes:

Americans’ once-in-a-generation job market has come to an end.

The red-hot hiring and rock-bottom unemployment that helped millions of workers find new gigs, boost their wages and reinvent their careers are giving way to more prosaic times. While the market is still healthy by many measures, signs of difficulty are creeping in …. And while the risk of getting laid off is still low, hiring has fallen beneath its pre-Covid level.

Many economists see a job market that has come back into balance, though some worry that conditions could continue worsening.

“The labor market cooled back to a strong place. This is a good labor market. But it’s not clear if the cooling is done,” said Claudia Sahm, chief economist at New Century Advisors, an investment firm. … “It’s a good time to have a job. It’s a harder time to find one.”

The Sahm rule is currently sending the right cautionary message about the labor market cooling, but the volume is too loud. The swing from labor shortages caused by the pandemic to a burst in immigration is magnifying the increase in the unemployment rate. At the same time, the demand for workers is softening. A recession is not imminent, but the risks of a recession have risen.

Here are some of my earlier posts on the Sahm rule. For more than two years, I have been thinking and writing about why the Sahm rule might not apply in this cycle.

According to

's analysis, the official unemployment rate captures the recent rise in immigrants, so the challenge in the Sahm rule is interpretation, not measurement. In contrast, he finds that employment levels in the household survey may be somewhat underestimated.The calculations use the three-month averages for the unemployment rate and the reason for unemployment. The timing convention for the changes in the composition follows the Sahm rule’s timing for the changes in the unemployment rate.

With a similar concern about the increase in labor supply from immigration, Ed Yardeni and Eric Wallerstein, in their rule, use the changes in the insured unemployment rate—the fraction of individuals eligible for unemployment benefits who are currently collecting them—instead of the national unemployment rate. Their rule is not close to triggering. One problem is that it excludes more than immigrants, such as excluding the long-term unemployed (more than 27 weeks) who are no longer eligible for benefits. Plus, the share of covered employment has moved sharply in recent years, unlike prior cycles.

Your columns are always informative. Thank you!

My sad takeaway is Michael Kantrowitz's comment that "the good news of unemployment rising is that it takes pressure off inflation." The sad note is the focus of these traditionalists is never about what we can do to maintain a near 100% employment rate (especially good-paying single jobs per person, not bad-paying multiple part-time jobs for 10-12 hour workdays to make ends meet). There's nothing wrong with inflation if people have the income gains to match inflation increases. Inflation just means that some are losers and others are gainers.

Leaving it to these pundits and the Fed where they think the Fed is the only one with the tools, inflation will never get solved, and it's usually the working class that get hit the most. Raising interest rates increases inflation since higher loan interest costs are passed on to consumers, and home buyers and credit debt holders face higher prices. The treasury bond holders (mostly people who don't need extra money) are making extra money for free, doing nothing for society, from the higher interest rates. Although most of these bond holders will re-invest their interest payments, some will spend it now, and soon the baby boomers will start to spend their interest earnings soon as they have more time to go buy a nicer car for America road trips or go on long travels to Paris or Florence. With today's higher interest rates with a high debt to GDP ratio, we now have government outlays in the month of this past June where Net Interest payments of $81B is almost higher than the combined amount of the National Defense at $67B and Medicare at $22B. The Net Interesting payment will soon be much higher than those two combination.

Lowering interest rates could help lower inflation at some level. There are a ton of other things on the fiscal side that can target and reduce inflation areas. The question should first be how can we maintain near 100% employment (good paying jobs) as our number one policy directive. One example is a federally funded Jobs Guarantee (JG) program for the local districts to decide what they need. This is just a buffer stock to help pick up when corporations cut jobs. Then when corporations start hiring again, the JG program have people with continued work experience ready to switch back into corporate work.

For inflation hot spots, do our homework! Find out where they are, learn what's causing them, and only then figure out how fiscal action can reduce those inflation spots. For example, lumber costs are high, leading to higher new home prices? Well, shall we reduce Canadian lumber tariffs? Rents are high? Should we restrict new housing permits that are for premium multi-million homes and city condos? Could we relax permit restrictions for housing project needed that are affordable for the working class? The construction firms may have new incentives to shift some of their workers from premium flats where it takes 50 workers to build an apartment for a family of three over to using the same 50 workers to build 10 apartments for the middle class. Still not enough construction workers? How about fast-tracking immigrants on the borders who have construction skills and give them those jobs. Everyone should be happy.

In summary, the question should be about how do we keep employment high as our number one job. That's more important than inflation since that can be easily managed by smarter people.