The Labor Market Is Strong

In March 2023, the U.S. labor market continued its rock solid push forward, with 303,000 more jobs and the unemployment rate back down to 3.8%. Are there cracks below the surface? Not really.

Those who want to trash today’s labor market will have a hard time doing so if they stick to the facts. In today’s post, I debunk some of the usual suspects from the haters on the right and left. Here are the main takeaways:

Recent gains in part-time work are good and necessary.

Immigrants have been key to resolving labor shortages and boosting growth.

Official statistical agencies give us the best read on people’s lives.

We came into the pandemic with long-standing problems. The reality is that the strong recovery chipped away at some of those problems, like wage inequality.

Finally, keep politics out of it. The labor market recovery began under then-President Trump and continues under President Biden. It’s not about them. It’s about workers.

Part-time jobs are not necessarily bad jobs.

As I discuss in my latest Bloomberg Opinion piece this week and on Bloomberg Surveillance today, the rise in part-time work is part of ‘rebalancing’ the economy and providing many workers with the necessary flexibility. Not everyone wants to or can work full time due to being in school, caregiving, a lack of affordable childcare, or health limitations.

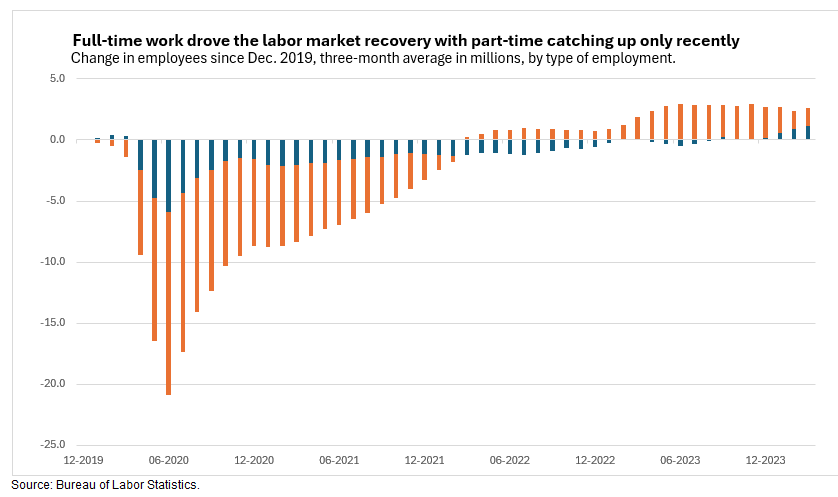

Until recently, the recovery in the massive number of jobs lost during the Covid recession had been largely full-time jobs (orange bars), not part-time jobs (blue bars). Full-time jobs coming back first was unprecedented relative to prior recessions. And the extra jobs now, relative to before the pandemic, remain mostly full-time.

The recent increase in part-time work could be a sign of trouble in the labor market, depending on why people work part-time. Currently, it doesn’t appear to be a problem. Only 2.7% of all workers are part-time because they can’t find a full-time position or economic conditions are bad. While the fraction has edged up, it is still near all-time lows. That’s good.1

Yes, even if part-time work looks good relative to past experience, that doesn’t mean it's as good as possible. Some part-time workers face barriers to working full-time.

Even though the vast majority of workers taking part time jobs are doing so “voluntarily” as measured by standard government classifications, that does not necessarily reflect such constraints as a lack of available childcare that preclude seeking full-time employment. Also, part-time work is not uniform across the labor force. More than 20% of women ages 16 and over worked part time in 2023, twice the rate of men. And of those women, 91% worked part time for non-economic reasons. The most common reason for prime-age adults to choose to work part-time is “family or personal obligations,” which would include caring for an elderly family member. “Issues with childcare” is another typical reason among women.

Even if many prefer the flexibility of part-time work, we can improve part-time jobs. My Bloomberg piece discusses ideas for employers and state and federal government officials. For example, job sharing, in which two or more workers share a job, generally a full-time job, usually leads to higher-quality jobs. Research shows they help women with caregiving responsibilities stay on their career path. Government programs that decouple health insurance and other benefits from employers are another way to ensure part-time workers have those benefits. Another is making childcare accessible and affordable to everyone. The strong labor market pushed up wages the most at the bottom, including part-time, service sector jobs.

The rise in unemployment in some states reveals how immigrants are helping address labor shortages.

What starts as a seemingly ‘bad news’ story of some states seeing a rise in unemployment actually has a ‘good news’ story at its core.

First, why is it important to look at the states when talking about the US economy? No one lives in “the economy.” Life is local. Life is at our kitchen table and in our community. The macroeconomic data ‘roll up’ the local conditions to give a representative view of the United States. It’s important, though no one person lives it.

Even policymakers tasked with decisions for the country should keep an eye on local conditions. Often, a local economy truly is only local, but sometimes, it tells us where the national economy is or is headed before the macroeconomic data.

What do we see now locally? The unemployment rate has increased notably in several states.2 Specifically, as of February 2024, the unemployment rate in 21 states had risen by 1/2 percentage point or more. The average increase was 0.7 percentage point, and these states had been, on average, 6 months above 0.5 percentage point. In contrast, the national unemployment rate had increased by 0.30 percentage point signaling no recession according to the Sahm rule. It is highly unusual to have such a large, lengthy, and widespread discrepancy between the state and national unemployment data.3

As I argue in a Bloomberg Opinion piece, a rising unemployment rate can be good.

Although this may appear dire, the increase in unemployment rates stem partly from the strength of the economy the past few years, strength that has attracted much needed immigration to meet the demands of a hot labor market. According to the Congressional Budget Office, net immigration totaled 2.6 million in 2022 and 3.3 million in 2023, rising from an average of 900,000 a year from 2010 to 2019.

As immigrants enter the economy, especially in large numbers, it can take them time to find work — likely even longer than US-born new entrants to the labor force. Moreover, immigrants have higher labor force participation rates overall than US-born individuals. The immigration process itself can create delays in legal employment, especially for humanitarian parolees and asylum seekers. More generally, an increase in the labor force has been long understood to be a “good” reason for why the unemployment rate temporarily rises as new workers find jobs.

Several analysts have attributed some of the upward drift in the US unemployment rate since mid-2023 to an increased labor force. It often takes time for new entrants to find jobs. A rapid increase in the labor force temporarily pushing up unemployment is the main reason I gave last year for why the Sahm rule might ‘break.’ That means that US unemployment would rise to 4% or slightly above for some time, but as the new entrants find jobs, it moves back down. So, the Sahm rule would trigger but with no actual recession.

Several states have seen a notable rise in their unemployment rate without a US recession. So what’s going on? Rather than gloom and doom, it appears to be a sign of immigration. A key insight is that immigrants are not spread evenly across the country. Typically, they move to areas with large immigrant populations. And that’s exactly what we see. The top three states by immigrants as a fraction of the state population have seen large increases in the unemployment rate.

And, consistent with the adjustment story, the unemployment rate is moving back down. Also, this is about immigrants. The rise in immigration appears to be pushing up unemployment rates, but that does not mean that immigrants are taking jobs from US-born people. In fact, the national unemployment rate of foreign-born people, not US-born ones, has risen most during the past few years.

The big ‘good news’ story of immigration is that immigrants are helping to solve the labor shortages. They are filling jobs that employers have struggled to fill. Early in the recovery, the news was covered with headlines about labor shortages and how they were causing higher inflation via higher wage costs. We don’t see those headlines now. Early in the pandemic, millions of workers left the labor market, especially US-born, many of whom retired or had caregiving responsibilities. The recovery in the US-born labor force was notably slower than the foreign-born. Immigrants were key.

From the lens of the labor market, immigration has been very good.

Statistical agencies are essential and credible.

The most absurd attack on the labor market is an attack on the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Everyone working on the data—from the Commissioner to the junior staff—holds their position due to their technical expertise in measurement. They are public servants, and the agency is independent:

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is the principal fact-finding agency for the federal government in the broad field of labor economics and statistics. BLS is an independent national statistical agency that collects, processes, analyzes, and disseminates essential statistical data to the American public, the U.S. Congress, other federal agencies, state and local governments, business, and labor. BLS also serves as a statistical resource to the Department of Labor.

BLS data must satisfy a number of criteria, including relevance to current social and economic issues, timeliness in reflecting today’s rapidly changing economic conditions, accuracy and consistently high statistical quality, and impartiality in both subject matter and presentation.

Does that mean every number is perfect? No. There are 160 million workers and over 30 million businesses in the United States, so it’s hard for statistics to keep up. Yes, the pickup in immigration during the past two years is a big challenge for the labor market statistics, but the BLS is meeting the challenge to the best of its ability. (Note: immigration is not new to the US.) The BLS moves quickly to give us timely information. Jobs Day follows only weeks after the survey. That’s impressive. And, of course, reports from businesses come in late. There is nothing sinister about revisions. Moreover, the economy is dynamic, and work arrangements are more complex than when the surveys started. Finally, budgets are limited, so the BLS’s ability to improve and expand the statistics is limited, too.

We must defend data quality, so the BLS deserves our support, not hate. As I wrote last year, ‘losing trust’ in statistical agencies is the path to learning less and less about the economy.

… businesses and households seem to be losing trust in the data and have become increasingly unwilling to participate in the surveys that underlie official statistics such as unemployment and inflation that, in turn, help inform decisions made by government officials and central bankers.

Lower participation rates can mean that the data initially collected are not representative of the population, and statistical adjustments are required for estimates to accurately reflect conditions. There are limits to the adjustments, especially for smaller or hard-to-reach demographic groups — often ones we most want to study for policies — such as minorities, those with less than a high school degree or young adults. And it can make it harder to sort out disagreements across surveys.

Tropes like the “BLS is an agent of the White House,” it is “cooking the books,” or its “statistics are meaningless” feed the downward spiral in trust. Official statistics remain our best source of information about the economy, but we must protect them. Without facts we can agree on, we will be without agreement on policy.

In closing.

The labor market has been strong for over two years and shows no sign of stopping. That’s very good. We have enough bad in the world, so do not turn the good into bad. If you cannot see good in this labor market, I don’t think you know what good is.

No, it is not perfect, and we must do better for workers. However, denying the strength in this recovery and warping it into weakness is counterproductive, no matter who you want in the White House next. It’s not about who gets the credit; it’s about how we build on this success.

Some argue that workers are being forced to take multiple jobs to make ends meet. However, only 5% of the employed currently work multiple jobs, the same as the fraction in 2019. The labor market in 2019 was also strong, though inflation was lower. The hardship story does not hold up for the country as a whole.

I define an increase as the three-month average of the state unemployment rate relative to the low of the three-month averages in the prior 12 months. The Sahm rule applies that same formula to the US unemployment rate, but these are not “state-level Sahm rules.” There is no reason that a 0.5 percentage point increase in a state is a trigger in the same way as 0.5 percentage point in the Sahm rule for the US. See here.

State statistics are less precise than national ones. The US unemployment rate comes directly from the Current Population Survey. The survey is not large enough to provide the state estimates alone; modeling is required, as are additional data sources. Even then, only the non-seasonally adjusted data match the national data. For example, according to the national data, the implied increase in the national employment rate from the labor-force-weighted state increases is 0.41, notably higher than 0.27. The state data are revised over five years with more source data and new seasonals so the gap could narrow. All analyses now on the ‘state Sahm rules’ use the revised data, not the real-time data.

Today’s clearly good news is the first time I’ve heard major news outlets attribute increased immigration numbers as a net positive to filling those persistent underemployment numbers and contributing positively to job growth and low unemployment trend. Thank you for also illustrating this positive trend.

Even forgetting immigration, unemployment tends to rise a bit in a recovering job market as word gets out that there is more opportunity and folks on the sidelines jump back into the labor force. That's why u-6 and the participation rate is good to watch. Thanks for your update!