Jay Powell's Greenspan moment

The Fed is increasingly concerned about "above-trend" growth. In the mid-1990s, Greenspan grappled with it, too, and wisely held off on raising rates. That's the right move again today.

The recent economic news, with few exceptions, has been great. The eye-popping numbers like the over 300,000 new payrolls in September or almost 5% real GDP growth in the third quarter aren’t likely to repeat. Even so, the labor market and growth look solid, and inflation is coming down.

Fed Chair Jay Powell affirmed that the state of the US economy is good when he spoke at the Economic Club of New York on Thursday. It was arguably his most optimistic remarks in over two years. A November rate hike is off the table, and another hold in December is increasingly likely. Good.

Could growth be too good?

Solid growth is one red flag from the Fed, and today’s post digs into why. As an example of the concern, here is Powell last week:

… the record suggests that a sustainable return to our 2 percent inflation goal is likely to require a period of below-trend growth and some further softening in labor market conditions.

We are attentive to recent data showing the resilience of economic growth and demand for labor. Additional evidence of persistently above-trend growth, or that tightness in the labor market is no longer easing, could put further progress on inflation at risk and could warrant further tightening of monetary policy.

A multitude of Fed officials have echoed the concern about ‘too-good’ growth. And you can see that thinking in the FOMC’s projections in September. They doubled their expectations for real GDP growth this year and, in tandem, removed 1/2 percentage point in rate cuts next year. The stronger-than-expected economic data reinforces the “longer” in the Fed’s “higher for longer” strategy.

There’s a logic to it. And yes, it’s in our friend, the Phillips Curve. It’s also embedded in the Taylor rules that the Fed uses to evaluate the level of the federal funds rate.1 When growth is above trend, it’s a sign of unsustainably strong demand. Big increases in demand—assuming that supply is not keeping up—put upward pressure on inflation. And that would complicate the efforts to bring inflation down.

How much is too much growth?

The danger of the Fed raising rates on “above-trend growth” is that we don’t know what trend is, also referred to as growth in potential output or y-star. Yes, there is a star in macro for every occasion; this is the most important one. It’s the key to long-term prosperity. If trend growth is higher than the Fed thinks, it could overreact to the high GDP growth and raise rates too much. In times of economic disruption like now, it’s especially tough to say what’s trend.

The recovery from the Great Recession and the second half of the 1990s are two periods when our understanding of trend growth shifted markedly and rapidly.

After the Great Recession in 2013, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that, on average, real trend (potential output) growth from 2012 to 2019 was 2.1 percent.2 By 2019, according to the CBO, trend growth in that same period was 1.6 percent. That is a meaningful reduction. Going from 2.1 to 1.6 implies it would take roughly 45 years, not 34, to double real GDP. And that rethink of trend growth rate occurred in only six years.

The evolution in thinking after the Great Recession is also evident in the Summary of Economic Projections. In late 2011, the central tendency for long-term growth among FOMC members was 2.4 to 2.7 percent. By the end of 2019, that range had fallen to 1.8 to 2.0 percent. A swing that large within such a short period should caution against believing we know trend growth now. Of course, trying to quantify potential is a useful endeavor. Models and data back these estimates, but especially now, we should be cautious in using them to guide policymaking.

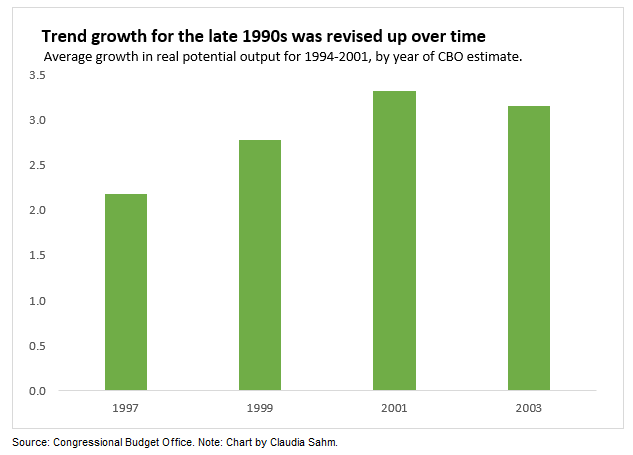

The mid-to-late 1990s were the exact opposite; we now think trend was higher than the initial estimates. Trend growth was revised up repeatedly and massively, implying that the pick-up in GDP growth was sustainable and did not risk higher inflation.

But that was not clear at the time. The Greenspan Fed was using the same logic as now in considering hiking rates since growth was above the estimates of trend. At least for the period in the mid-1990s, Greenspan decided that the economy had more room to run than the trend estimates in the hand suggested. That was a good call. Strong GDP growth continued, and inflation did not pick up.

Here is an excerpt from Ben Bernanke’s book, 21st Century Monetary Policy:

The economy [in mid-1996] was growing at a solid pace—about 3 percent in the first half—and unemployment, at 5.5 percent, had fallen modestly below the staff’s estimate of the natural rate. By the usual Phillips-curve logic, inflation should become a problem, and … argued for rate hikes beginning soon.

Greenspan, however, was not so sure and was inclined toward caution … [He] had developed a view of why wages and prices were rising only modestly, despite the expanding economy and tightening labor market. It turned on what he saw as an acceleration in the pace of technological change.

It’s part of the Greenspan lore that he held the FOMC off from hiking because he sensed a productivity pickup that was not in the aggregate data. (It is now.) Bernanke throws some cold water on the praise, among other things, arguing that the Greenspan Fed did raise rates six months later.

But I’ll take it. Giving inflation another six months without a pre-emptive strike over “above trend” GDP growth would be valuable now. To be clear, 2023 is radically different than 1996. The ‘Greenspan moment’ is about being cautious with estimates of trend growth and the early data economy.

Why do trends break?

The concept of potential output sounds abstract, and the models that estimate trend growth are even more abstract. Remember, our 27 trillion dollars of GDP is the decisions made by American families, businesses, and the government. The decisions and technology can change, sometimes dramatically and with lasting consequences. That makes it hard to get trend right.

Monetary policy and macroeconomics often take a 30,000-foot view of the economy. That can be useful, but it can miss changes on the ground floor. Plus, relying on past relationships in the economy, as any macro model does, can sell us short.

Here are excerpts from some pieces I have written for Bloomberg Opinion that discuss how our country’s economic potential can expand or contract.

Place-based inequities in the US are dramatic and costly. Nationally, the unemployment rate has held near historic lows of 3.5% for more than a year. But unemployment is far higher in several parts of the US, many of them rural, such as Yuma County in Arizona (15%) or Rolette County in North Dakota (10.5%). And when a region is distressed, more job openings do not push up inflation — they create economic opportunities for workers and can boost productivity. October 12, 2023

Letting women’s labor force participation slip again could also be risky for productivity growth. The reason why is that education levels for women continue to rise, setting them up to boost productivity. However, gaps in careers, such as taking time off to provide caregiving, can lead to a loss of skills. And an inability to pursue careers that are currently less family-friendly can keep women from contributing their potential to the economy. Technology that allows for things like working from home helps but fails to apply to many jobs.

Fully integrating women into the labor market would substantially boost economic output. The labor force participation rate for prime-age men is 10 percentage points higher than it is for women. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco examined the differences in employment employment, hours worked, educational attainment, educational utilization and occupational allocation … [and] calculate that closing the current gap with women would have added $1.7 trillion, or 8%, to gross domestic product in 2019. The largest contributor — $600 billion — to the additional output was equalizing employment rates, underscoring the importance of getting more women into the workforce. ~ October 6, 2023

Declines in labor productivity are the primary channel through which higher temperatures affect the economy. Researchers with the Atlantic Council, a moderate think tank, estimated in 2021 that they cost the US economy $100 billion annually by reducing labor productivity, or around 0.3% of gross domestic product. If businesses and the economy don’t adapt, the reduction in productivity could reach 0.5% of GDP by 2030 and 1% by 2050. That’s just one of several estimates, but the negative effects of rising temperature on productivity is a common conclusion.

The topline estimates mask considerable differences between various parts of the economy. Although in the corporate sector the effects are muted, in the agriculture sector, where workers are mostly exposed to rising outdoor temperatures, productivity is significantly reduced. Moreover, the agriculture economy has shown little adaption the last 50 years to increasing temperatures, suggesting the long-term effects on productivity will likely be as large as we have seen in the short-term. ~ August 21, 2023

An even more troubling flaw is that estimates of potential output basically assume that our past must be our future. As one example, it takes systemic racism that has kept many people of color on the sidelines of the labor market as a permanent feature of the economy. Alex Williams at Employ America points out that the CBO assumes unemployment rates by age and race seen in 2005 are the lowest we can attain without sparking inflation. In other words, our potential is stuck in the past.

The first change to our thinking should be defining the potential of the economy in terms of future opportunities for all workers, not the historical barriers that some have faced. Using the current approach to potential output to evaluate government programs implicitly accepts that discrimination is embedded in the economy. An unobservable, educated guess based on embedded racism should not be used to judge programs designed to push the economy to full employment and reduce inequality. ~ April 9, 2021. (And my Substack version.)

That’s the tip of the iceberg in ways that trend growth can change. One common theme is to bring in people and communities on the sidelines. The Fed is not key. It’s all levels of government, businesses, and workers that are.

In closing.

The Fed is wrestling with the question of how good is ‘too good’ when it comes to economic growth. As with Greenspan in the mid-1990s, The answer hinges on what’s trend growth, which no one can know with any confidence.

Today’s Fed talks a lot about being “cautious.” That’s a welcome change relative to last year; it must also apply that principle to its ability to judge the economy’s trend growth. It’s not time for a victory lap with inflation still too high, and it’s not time to pour cold water on the good news of recent growth.

Sometimes, good news is good news, even for the Fed.

Bonus: Here’s my interview with Bloomberg Surveillance. We cover considerable ground on the economy and the Fed. The Greenspan moment comes up, too.

My post for paid subscribers coming this week is a deeper dive into Taylor rules and, more generally, the Fed’s “reaction function” to data on the economy. Subscribe above so you don’t miss out.

The Congressional Budget Office is a primary source for estimates of potential output growth. The Fed’s estimation approach differs some, but the resulting estimates are similar. CBO uses a bottom-up approach with labor, capital, and productivity estimates. Here is a good explainer from the St. Louis Fed on the different approaches.

This Article from The Atlantic I thought was interesting to read from a few days ago. America truly doesn't need a recession as we've come this far from inflation off its peak in July of last year. A fed induced recession would be tough and yes especially for women and just as important people of color. Hopefully Powell sticks to his word and doesn't hike in Nov and Dec.https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/10/america-recession-disinflation-fed/675700/

Another reason for the Fed to hold is to watch for (further?) signs that high rates are having an effect. While people tend to focus on the housing sector — an important transmission channel — and don’t see much distress for a whole assortment of reasons, there are other places to look that urge some caution. Examples for consumers include auto loan and credit card delinquency rates, and I’ll bet lower rated corporates are also having trouble. All corporates and commercial real estate borrowers who must refinance are facing high costs. Lastly, while SVB was an egregious example of a bank doing a really bad job of managing their asset/liability mismatch and their designation of assets held for sale vs assets held for investment, they will not be alone.