Racism skews our beliefs about what's possible

Racial economic injustices of the past and present do not have to be our future. But that's what tools like potential output assume, so it's time for new tools.

“Fears of a Too Hot Economy Ignore Racial Inequality,” my recent piece for Bloomberg Opinion discusses how “potential output”—an abstract concept that inflation hawks have wielded against economic policies—takes systemic racism in the labor market as immutable. It’s not. I lay out the problem here and suggest three ways to improve our tools and thus improve the economic advice we give.

To be honest, I had never thought about the racial assumptions in estimates of potential output, despite using it throughout my career in macroeconomics. I knew the tool had flaws, as I wrote about in an earlier post. Then Gbenga Ajilore asked me in disbelief about a post he’d seen on its racial assumptions. It took someone outside of macroeconomics, someone who is a Black man economist, to wake me up and get me to dig into the methodology. I am so happy he did. It’s unacceptable.

First, a definition of the concept:

What is “potential output,” and why is it central to the debate over fiscal policy? Simply put, it is an estimate of how much gross domestic product the U.S. can produce given how much people want to work, the capital that businesses have and how effective these inputs are at making stuff, namely, productivity. The conventional thinking is that producing more than potential will “overheat” the economy, leading to much higher inflation.

Olivier Blanchard, a top academic macroeconomist who served as the Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund, has used estimates of potential output from the Congressional Budget Office to argue recently against Biden’s rescue package. He claims that the latest legislation would push GDP past its potential and reminds us how that had been disastrous in the past:

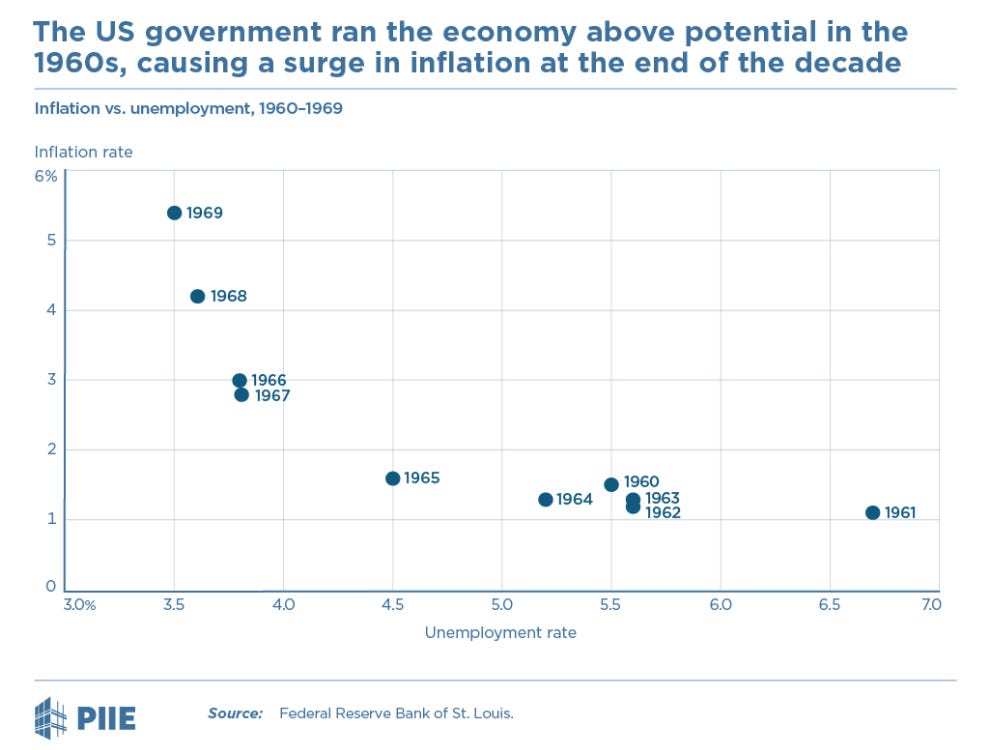

A relevant comparison here is what happened in the 1960s, shown in the figure below...From 1961 to 1967, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations ran the economy above potential, leading to a steady decrease in the unemployment rate down to less than 4 percent … In 1967, however, inflation expectations started adjusting, and by 1969, inflation had increased to close to 6 percent and was then seen as a major issue. Fiscal and monetary policies tightened, leading to a recession from the end of 1969 to the end of 1970.

Correlation is not causation. Couldn’t other factors be at play? Regardless, one result of the stagflation of the late 1970s was a firm belief among economists that unemployment too low, an economy operating past its potential output, would lead to inflation and then only a severe recession could bring it back under control.

But how do we know how low unemployment can go? Basically we guess and lean hard on history to predict the future. Alex Williams at Employee America calls attention (the post Gbenga mentioned) to racial assumptions in the CBO’s estimate of the natural rate of unemployment, a key component of potential output:

So, CBO assumes unemployment rates in different age and racial groups in 2005 are the lowest we can attain without sparking inflation. Why 2005? The Black unemployment rate then was 10%. How can 1 in 10 Black workers without a job be an economy at its full potential? And before you point to “structural factors” as a cause of racial disparities, remember that Black unemployment was 6% in 2019—well below its level in 2005—and that was a time with low inflation.

The flaws in estimating potential output and the natural rate of unemployment go back to the very beginning. In some ways it started out well. Art Okun, while on staff at Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers, developed the measure. He was part of a movement by the CEA led Walter Heller to shifted the economic goal posts from debt sustainability to full employment. That’s good and an ongoing fight.

Ah, but full employment was inextricably linked to inflation even then. That’s an economist ‘innovation’ that now is ‘doctrine.’ In contrast, the goal of the Employment Act of 1946 is “conditions under which there will be afforded useful employment for those able, willing, and seeking to work .” No one wants their paycheck eaten up by rising prices, but for millions of Black families there is no paycheck from which to eat. The 4% unemployment rate that Okun proposed as the best we can do was around 8% for Black workers. That’s better than CBO’s assumptions now but not by much.

To be relevant in the current policy debates, economists must accept the need for new tools and new thinking. Inflation is not what’s holding us back. It’s an economy riddled with racism and injustice. The Administration and Democrats in Congress are pushing policies that are designed to combat inequities in our economy—from a robust recovery for all to clean drinking water to good jobs in care work. These efforts to change the system cannot be evaluated by metrics stuck in the past.

Our thinking should be defining the potential of the economy in terms of future opportunities for all workers, not the historical barriers that some have faced. Using the current approach to potential output to evaluate government programs implicitly accepts that discrimination is embedded in the economy. An unobservable, educated guess based on embedded racism should not be used to judge programs designed to push the economy to full employment and reduce inequality.

The Federal Reserve is feeling its way toward new metrics, though it too lacks a working definition of “maximum employment,” despite it being part of its dual mandate. Even so, to hear Chair Jay Powell and a chorus of Fed officials draw attention to the million jobs lost in this crisis and the crushingly high unemployment rates, especially among Black and Brown workers is notable. The Fed has steadfastly, downplayed the risks of overheating, that is, inflation spiraling out of control. They even changed their framework in an attempt to break their long history of overreacting to inflation. Jay’s test is coming, and he’s ready. But that’s not enough.

Second, we need more timely and more detailed economic data by race, gender, and their intersection that can inform policy. Rhonda Vonshay Sharpe, founder and president of the Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race and Bloomberg Opinion contributor, explain that with existing data and standard analysis, we cannot fully grasp the suffering among minorities in this crisis and the challenges they face. Money allocated to statistical agencies to enrich their data would pay off in terms of better policies.

A reader asked why I only discuss disparities among Black and Hispanic workers in my piece. What about Asians like him? That’s a fair point, as is the exclusion of Native Americans, who live with some of the most severe economic conditions in the country. Again, with better data we could pinpoint the groups who are being left behind historically. It’s especially urgent now. We know many people of color have been hard hit in the Covid crisis, with elevated death rates and as essential workers exposed to the virus every day. We are not back on track until everyone is back on track.

Finally, we must understand that discrimination is holding back economic potential. The $180 billion for research and development in the American Jobs Plan won’t attain its maximum impact if we don’t include researchers, such as in sciences, engineering, and medicine, who are also minorities. Lisa Cook, a professor at Michigan State University, found that discrimination and racial violence in the 19th and early 20th centuries led to 60% fewer patents by Black inventors during the period. A recent survey by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation found that Black people make up 0.3% of innovators, far below their 11.3% share of the population. That lack of diversity reduces GDP and our true potential.

Systemic racism is immoral. It harms people due only to the color of their skin. And it’s an economic disaster. The concept of potential output and how far we are from it is an important, albeit abstract. However, it’s worse than useless if we define it in ways that accept discrimination at work, accept the scientific breakthroughs we never had, and accept economic lives held back as a permanent feature of American life.

Reaching our potential is about getting the last person across the finish line. Thinking “on the margin” is a powerful lens in economics. One we must apply here too. The average worker does not tell us much about how far we are from full employment. It’s the people on the cusp of getting jobs—often come from marginalized groups, economically depressed areas, and have less education—who tell us how close we are. Getting us across the finish line as a country, means getting those people there too. Potential output as we estimate it today using our dismal past is not helping. Applying it ruthlessly to argue against policies that could serve the underserved is self defeating.

It’s time for economists to update our tools and open our minds to what’s possible, and it’s time for policy makers to engage with the economic realities of systemic racism and fight to end it. And we need better tools to do it.

I appreciate that you (and others such as Gbenga Ajilore) raise this point. I agree that it is very important to be aware of racial bias and that we should be extra careful when such bias is pointed out to us, because it may be so ingrained as to go unnoticed on casual inspection. However, at the moment I do not think that the issue you identified here constitutes or contributes to systematic racism. In short, the aggregate unemployment rate itself will always reflect the differences in unemployment rates between racial groups. The approach of disaggregating the estimate of the natural rate of unemployment at racial levels will only change the weights assigned to the different racial groups. Furthermore, precisely because of systemic racism, it is very useful to keep an eye on the disaggregated data.

I'll focus on the aspect of racism in the estimate of potential output. I have yet to grapple with your critique of potential output generally, but for this question we should take the potential output concept as given. The first question is how this actually works and compares to an approach without racial disaggregation. As I understand it, based on the CBO document you cite, first the natural rate of unemployment is estimated for each racial group separately (as their unemployment rate in 2005). Then an average weighted by population share is taken. So in 2005 the estimate for the natural rate is just the unemployment rate in that year. It would be the same if there was no racial disaggregation, where you would just take the overall unemployment rate in 2005. The difference between the two approaches comes in later years, when the weights of each racial group are updated, but not the estimate of of the natural rate for each racial group. So, if if the share of blacks and African Americans increased, while the share of whites decreased, greater weight would be put on the higher unemployment rates in 2005 of blacks and African Americans, leading to a higher estimate of the overall natural rate.

So, how large would such an effect be? I cannot find exact numbers on the change in racial composition of the labour force in the US between 2005 and now. But I can use some numbers for a back of the envelope calculation. On Wikipedia I find that the share of whites in the overall population declined by a 2.7% between 2000 and 2010. Let's suppose that 1) the rate of change was similar between 2005-2021, so 1.6 x 2.7%=4.32%. 2) To get an upper bound, let's suppose declining share corresponded to an increasing share for the black and African Americans only, who had an unemployment rate of 10% in 2005. Based on the graph whites had an unemployment rate of 5% in 2005. So the shift in weight would lead to an estimate of the natural rate of unemployment that is 0.0432 x 0.05= 0.22% higher than it would be in an approach without racial disaggregation. In general such a number will be quite small because we are multiplying two differences (change in population share and difference in employment rate) that are each in the order of a couple percent. (I do not know enough about macroeconomics to assess how large an effect a change of 0.22% in the estimate of the natural rate of unemployment would have on fiscal policy, but I would expect it is small.)

In general, the racial disaggregation approach doesn't seem racist to me, because it is only about adjusting the weights of the races. The systematic racism that causes differences in levels of employment will be present in the 2005 employment figures whether we disaggregate or not. It will also be present in the 2021 unemployment data. On the other hand, the adjustment in the population weights seems neutral to me. If the share of blacks and African Americans had increased, it would lead to a lower estimate of the natural rate of the natural rate of unemployment compared to the approach without racial disaggregation.

In fact, precisely because of the regrettable and undeniable presence of systematic racism, it seems to me to be actually useful to disaggregate unemployment data at the racial level. An important observation that you make is that the unemployment rate of blacks and African Americans was much lower in 2019 than in 2005 (from 10% to 6%). A possible interpretation of this number is that it corresponds to a decrease in the natural rate of unemployment for that racial group. This would have been hard to notice if we only focus on aggregate unemployment data. Even if we take 2019 as near the natural rate again, the difference in the aggregate between the unemployment rate in 2005 and 2019 would be small and perhaps not prompt a reassessment. It is only at the disaggregated level that we see that there is a need for updating the natural rate of unemployment for one racial group. (One hopes that this change corresponds to decreasing racism in the intervening years, but that is both speculative and very optimistic.)

The concept of "potential" was always a false and misguiding metric. When you factor in discrimination it makes the concept even worse. Hopefully it will be the reason to discard it from policy discussions once and for all.