The SEP Strikes Back

The Fed voted to hold the federal funds rate at 5.25% last week, but its Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), for which there's no vote, raised borrowing costs and upped the odds of a recession.

“Don’t underestimate the Force.” ~ Darth Vader

Forward guidance is the Force of monetary policy, and the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) is one of its primary tools. Forward guidance is an approach the Fed uses to influence borrowing costs for firms and households now by signaling what it will likely do in the future.1 It was created at the end of the Great Recession when the federal funds rate was at zero, which left little scope to push down borrowing costs and boost economic activity. So, how does it work?

Financial markets are ‘forward looking’ and want market interest rates and asset prices to reflect future federal funds rates as soon as possible; as a result, forward guidance can be a powerful way for the Fed to move markets. It is also the dream tool of macroeconomic theory, which leans hard on the role of expectations in monetary policy. The Fed uses various forward guidance tools: speeches, interviews, press conferences, and forecasts.

Today’s post—with a deeper dive for paid subscribers—is on the Summary of Economic Projections. I am critical of the SEP, but I appreciate its purpose and why it deserves improvements.

Unlike changes in the federal funds rate, the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) is a non-consensus and non-transparent tool. Each official submits their economic forecast based on their assessment of “appropriate” monetary policy. Think of it as every Fed official playing Fed Chair for the day. And one projection is the Chair’s, albeit unidentified like the rest. It is a valuable internal tool to quantify the different viewpoints of the committee, but it’s questionable how well it serves the Fed in public.

The SEP hiked.

Once again, at last week’s press conference, the Summary of Economic Projections took center stage and moved markets, even though the Fed unanimously voted, as expected, to hold the federal funds rate steady. Minus the SEP, markets would have almost certainly moved less. Instead, the SEP surprised and confused many, as witnessed by conflicting interpretations. That all-too-common occurrence is especially problematic now.

Most news coverage focuses on the median forecast across the 19 FOMC participants for the “appropriate” federal funds rate and each macroeconomic variable, like GDP or inflation.2 The so-called ‘dot’ plot with all 19 federal funds rate paths receives considerable attention in addition to the median. No one, including the FOMC, knows who’s who unless they reveal themselves. And there’s no coordination among members.

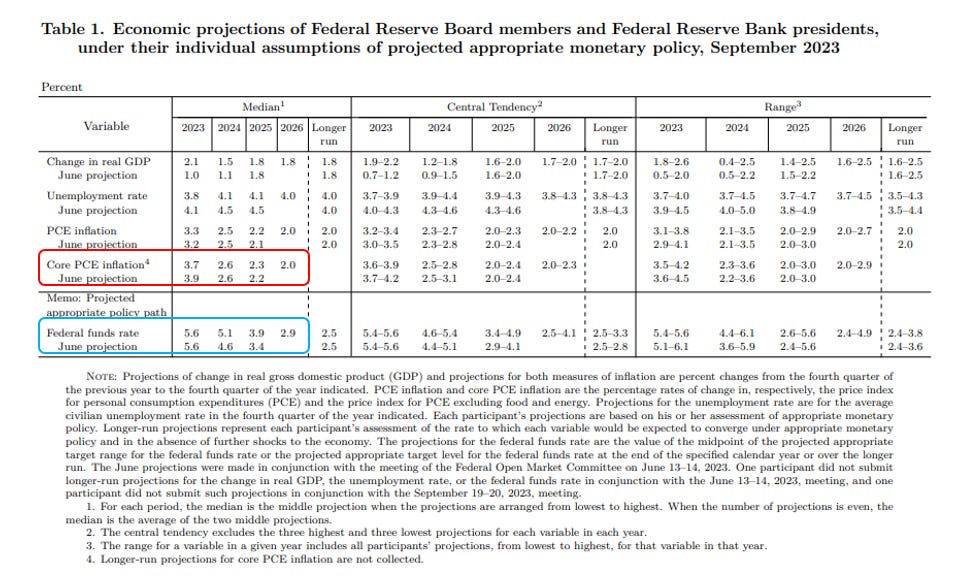

Let’s look more closely at the new SEP. The median forecast for PCE core inflation (red) and the federal funds rate (blue) are two critical pieces of information. For each variable, the first line is the new September SEP, and the second is the prior June SEP. First, the good news is that the data on core PCE inflation has come in lower than the Fed expected in June, so the median projection moved down for this year. Good. We have not seen many downward revisions to inflation in the past few years.

The projections raised the path of rates. It might not look like much, but the 1/2 percentage point upward revision to the federal funds rate next year and carried into 2025 is a big deal. It pushed 10-year Treasury yields to a 16-year high, and the stock market dropped. Some of these reactions unwound, but it’s a lesson in how powerful the SEP is. The SEP, a non-consensus, non-transparent tool, can move borrowing costs for people taking out a mortgage, student loan, or payday loan, carrying balances on their credit cards, or needing a loan to start a new business. The SEP may please macroeconomic theorists, but it’s disruptive to everyday people and not aligned with the Fed’s commitment to be “careful” now.

Finally, some interpreted the new Summary of Economic Projections as expecting a “Goldilocks” economy with higher growth and lower unemployment. But, the extra tightening in the SEP and the reaction it caused put the soft landing at risk.

Below the fold for paid subscribers, I go deeper into the SEP, including its implications for the real federal funds rate, which peaks *next* year under the SEP forecasts, and research on how forward guidance has shortened the lags in monetary policy. Subscribe to read more.

The rest of this post focuses on what the new SEP tells us about the Fed’s policy thinking, especially for next year, and the implications for the economy.

Cuts in the fed funds rate won’t slow the tightening.

The new SEP increased the path of the nominal and inflation-adjusted (real) federal funds rate relative to the June SEP. In both SEPs, the nominal federal funds rate (left chart) steps down each year, implying that the Fed expects to cut next year. In the June SEP, 100 basis points of cuts were expected, and now only 50 basis points.

However, nominal rates only provide part of the picture. The real fed funds rate (right chart) is more relevant for economic decisions. For example, for a business taking out a loan, the interest rate minus the rate of inflation is more important than the nominal rate on its own. Higher inflation means that the dollars to repay the loan are less valuable, which helps the borrower and hurts the lender.

Inflation is expected to fall faster than the federal funds rate in the June and September SEP, so the real rate rises next year.3 In fact, the real federal funds rate peaks next year. That was true in the June SEP and is much more pronounced in the new SEP. The step down in the federal funds rate—which would remove some of the downward pressure on the economy—is expected to be more gradual.

And why do Fed officials think they need to hold down the brakes—in nominal or real terms—longer? Why is the real rate peaking next year? It’s hard to say. The monthly percent change in core PCE prices has slowed steadily this year, which is at odds with more aggressive tightening. The Fed lowered its core PCE inflation forecast relative to three months ago to 3.7% Q4/Q4. And even that’s probably too high; it would require monthly readings to pick up substantially through the end of the year. The Fed did lower their forecast for the unemployment rate at the end of this year and put through a massive upward revision to GDP growth to better align with existing data. With an apparent slowdown in hiring and inflation coming down, it’s hard to see why the additional tightening, especially the climbing real rates, is warranted.

Some Fed officials are openly concerned about the path of the real federal funds rate, such as New York Fed President John Williams:

The need for more rate hikes is “an open question,” Williams told the Times. If the inflation rate keeps falling, the central bank may need to lower interest rates in 2024 or 2025 to ensure that real interest rates don’t rise further.

As key US inflation measures cool and the Fed maintains rates at current levels, real rates increase, which “won’t be consistent with our goals,” Williams said.

Williams has a point that raises challenging questions about the new SEP. A peak real rate next year means that by pursuing ‘higher for longer’ for the nominal rate, the Fed is pursuing ‘higher and higher’ for the real rate. That’s a clear recession risk. The higher funds path could have made sense if the SEP had a higher inflation forecast, but that would have been odd given the incoming data.

The lack of internal consistency in the SEP and the lack of consensus is a problem. With the economy already cooling, how is that appropriate policy? For example, the net gains in payroll employment are at half the pace from the start of the year. The rate of employees quitting their jobs has fallen back to the pre-pandemic level. Plus, inflation is trending down. That’s not victory, but it’s hard to understand how turning the screws harder next year makes sense. And that’s not “proceeding carefully,” Powell promised multiple times last week.

SEP may have shortened the lags in monetary policy.

Forward guidance is a relatively recent tool that appears to be powerful enough to have challenged a long-standing maxim of monetary: “long and variable lags.”

In a research note from the Kansas City Fed, Taeyoung Doh and Andrew T. Foerster argue that the forward guidance has shortened the lags in the effects of federal funds rate changes on financial conditions:

Financial markets may react to changes in forward guidance on the future path of the federal funds rate and changes in the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet even before the FOMC changes the federal funds rate, suggesting lags in policy transmission may have shortened since 2009.

If financial market conditions tighten as policymakers provide forward guidance, the proxy fund rate [which incorporates public and private borrowing rates and spreads] can rise, even if policymakers have not raised the federal funds rate. For example, Choi and others (2022) note that the proxy funds rate had already risen to about 2 percentage points in February 2022 before the FOMC increased the actual target for the federal funds rate in March from the 0–0.25 percentage point range.

The proxy funds rate (green) that includes the (forward-looking) market reactions is notably higher and moved up faster than the funds rate in this tightening episode. That feature helped the Fed “front load” and amplify the effects of monetary policy in 2022.

The researchers also find that the lag between changes in the funds rate and the peak effect on inflation is shorter with forward guidance. Even so, the lag is about one year, consistent with more effects on inflation coming from last year’s hikes. Moreover, the lags are imprecisely estimated with forward guidance since Great Recession.

Why is this finding important? If the Fed believes that the lags are shorter now, as several Fed officials, including Powell, have said publicly, it will be less patient in seeing inflation come down. The apparent recent pickup in GDP, the housing market (contested), and ongoing low unemployment could mean that the restraint from prior rate hikes is waning, and the Fed needs to do more. That view is broadly consistent with the new SEP and other comments from Fed officials. But it requires two judgments: first, the limited experience does translate to shorter lags, and the pickup in activity is real. See my post on data revisions.

In closing.

As the world changes, so must the Fed. However, given the critical mandate of the Federal Reserve, its policies and tools must change responsibly. The Summary of Economic Projections added power that the Fed needed. But it’s taken on a life of its own, and the SEP either deserves a rethink or a break.

Most disconcerting about the Summary of Economic Projections is that it’s not a consensus tool, unlike the federal funds rate and the balance sheet. Far too often, the Chair spends much of the press conference trying to wrest attention back away from the SEP. That’s futile, and after more than ten years, the Fed should understand that.

If you want to proceed carefully, you can just use careful tools.

Thank you again for being a paid subscriber. If it were not for you, I could not continue writing here. Requests are always welcome for future posts. If you have colleagues and friends who would enjoy my writing, you can give the subscription as a gift.

Quantitative easing—when the Fed buys assets like U.S. Treasury bonds and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)—is another unconventional monetary policy tool, along with forward guidance. Quantitative easing has its issues; the Fed and markets even disagree on how it works. Forward guidance is easier to see in action and, in my opinion, is more powerful. Here is a helpful explainer of unconventional policy from the St. Louis Fed.

Note that the median forecast in the SEP is for each variable, not one official across all variables. So, the median forecast for real GDP could be from a different person than the median core inflation. That makes it difficult to tell an internally consistent ‘story’ from the SEP. The full forecast for each individual, though still anonymous, is published six years later with the transcripts, but by then, everyone has moved on.

Core, not total inflation, is what the Fed uses for its calculation of the real natural rate of interest, also known as r-star. And it is used here to calculate the real federal funds rate. Regardless of using total or core inflation to deflate the nominal funds rate, the new SEP implies a higher real federal funds rate next year and in 2025.

Great post! Both timely and thoughtful. Job growth is down by half. And over the last year 77% of all new jobs were in healthcare and education. The rest of the economy is creating 70k jobs a month. It won’t take long for these real rates to turn that number negative.

Thank you for highlighting the important difference between real and nominal rates.