What to expect when you're expecting inflation?

New research from Jeremy Rudd, a senior adviser at the Fed, made a stir last week. Inflation expectations might sound like a snoozer. Nope, they're a big deal. His paper is too.

Last week, Fed Chair Jay Powell spoke after the Federal Open Market Committee meeting. He had a lot to say about inflation and about inflation expectation:

“Our framework for monetary policy emphasizes the importance of having well-anchored inflation expectations, both to foster price stability and to enhance our ability to promote our broad-based and inclusive maximum-employment goal. Indicators of longer-term inflation expectations appear broadly consistent with our longer-run inflation goal of 2 percent.”

Uh, expectations? What’s that about? The Fed’s dual mandate is price stability and maximum employment here now not in the future. For the past twenty years, inflation—that is, the increase in consumer prices year after year—has been pretty stable around 2%. The Fed want to keep that going. It’s half of the job Congress gave them.

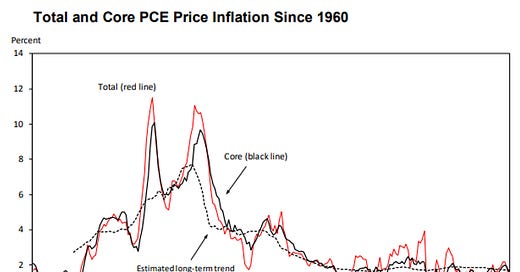

Source: Jeremy Rudd (2021). Note “core” is the prices excluding food and energy. PCE is Personal Consumption Expenditure prices, which is the series that the Fed targets.

To keep a good thing going, it is helpful to know what are the key drivers. Mainstream academic macroeconomists and central bankers latched onto the idea decades ago that inflation expectations were key. So the story goes, how much consumers and businesses expect prices to rise is how much they will rise in reality1. Their expectations about the future change their behavior now. For examples, if they expect prices to increase then demand higher wages which, in turn, requires businesses to raise prices, and so on and so on. Eventually the spiraling prices seep into the macroeconomy more broadly. The Fed must raise rate which leads to layoffs. We got a full on shitshow [technical macro term] in the economy. Very bad.

But, what’s that you say? How could expectations set that off? Wait, you have no idea how much inflation will be next year or the year after? Don’t worry, the Fed is more than happy to help. It believes that if it tell us that inflation will be 2%, you will listen and expect the same. Voila inflation expectations are stable at 2%. Stable prices in the dual mandate, check mark. But is that really why inflation hasn’t changed much?

Have you ever listened to a Fed press conference? Have you ever thought hard about the likely rate of inflation next year and five years ahead? If you aren’t a macroeconomist or a Fed watcher, I doubt it. As a PhD student in macro, I learned all that theory and I now watch every Fed press conference. I know why inflation expectations are considered useful in our models, and I know in my daily life I worry more about my paycheck than my grocery bill. Of course, I don’t want to pay more at the grocery, but also I know that those prices are basically beyond my control. My wages aren’t much better. I can’t think it and get it. Most of you can’t either.

And yet, the idea that the Fed can’t think 2% and get it is heresy in macroeconomics. Stable prices come from stable expectations, we said so. But reality don’t care. In fact, since the Great Recession, the Fed consistently fell short of its 2% target.

Reality Bites

In January 2014—over seven years ago—Alan Detmeister, Jean-Philippe Laforte, and Jeremy Rudd wrote a memo to the FOMC, delivering some bad news about inflation:

The observed evolution of the empirical inflation process over time, the difficulty we [the staff] often have in explaining historical inflation developments in terms of fundamentals, and the lack of a consensus theoretical or empirical model of inflation all contribute to making our understanding of inflation dynamics—and our ability to reliably predict inflation—extremely imperfect.

Fedspeak translation: We don’t know what’s driving inflation. You don’t either. The memo also discusses why inflation expectations aren’t likely a good explanation.

Then in June 2014, Jeremy Rudd spoke at an FOMC meeting, where he answered questions about a (still-not-public) memo by Deb Lindner, a very senior inflation expert at the time. Rudd’s exchange with Jim Bullard, Federal Reserve Bank President of St. Louis an absolute gem:

(We all knew Jeremy is witty, though I doubt Bullard laughed at that one.) The staff made clear to the FOMC, you cannot just think 2% and get it. Do something.

Years later Fed officials finally threw in the towel and admitted they would not get 2% inflation without trying harder. They did not jettison inflation expectations, and frankly the staff never did either, but they did rethink their approach to achieving their dual mandate.

Lots of outside academics weighed in too. Way back in 2019, current-day hawks, Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard, argued that 2% inflation target was too low. They wanted 4%. Here’s a summary:

“At a time when inflation has for years remained slightly below the Federal Reserve's target rate of 2 percent, a debate has broken out among macroeconomists over whether to raise inflation, and the target, further—for example, to 3 or 4 percent—by adopting an easier policy stance …

The debate has drawn some distinguished experts into the fray. On one side, for example, are Olivier Blanchard, Jordi Gali, Adam Posen, and Lawrence Summers, who favor an inflation target of 3 or 4 percent, which would require the Fed to lower its policy interest rate in the near term.

Be careful what you wish for and welcome to 2021.

In the end, the Fed settled on “average inflation targeting” and kept the target at 2%. It may not sound like much of a change, but the average requires data not forecasts, and, importantly, you must wait a little longer to get the data. The Fed more or less said that would wait to see inflation settle in at 2% before they begin to raise rates. Good. One bad side effect from raising rates too soon is stunting the recovery of jobs. Maximum employment is the other side of the mandate.

I don’t know how the Fed landed on the new framework. The transcripts from the FOMC meetings are released after six years. It would be a real service to make everything related to the framework review public immediately.

Fast forward to last Friday, and along came, Jeremy Rudd’s FEDS Working Paper on Friday, “Why Do We Think That Inflation Expectations Matter for Inflation? (And Should We?).” It went ‘viral’ #EconTwitter and Bloomberg covered it.

Nothing in Rudd’s paper surprised me both in substance and in tone. I worked with Jeremy for over a decade. He’s a traditionally-trained, mainstream macroeconomist and an iconoclast. Great combo, and yes, those exist at the Fed. In fact, divergent views among the staff even encouraged now. (Believe me not everyone is so encouraging. Ahem.) Groupthink is dangerous and it goes well beyond inflation expectations. Macro must do better. The Fed is trying.

A Call to Action

Rudd’s paper is a call to action. It’s a plea for us to really understand inflation.

He does not offer up the Holy Grail, “What the hell is driving inflation?” Instead, he carefully argues that mainstream macroeconomists and central bankers don’t know the answer, though most think they do. Moreover, our blithe ignorance could bite us in the butt when doing monetary policy, harming all Americans.

Using theory and empirics—every PhD in macro should read it carefully—Rudd argues that the centrality of inflation expectations in macroeconomics rests on very shaky grounds. We all know that building a house on sand is a bad idea. Rudd essentially argues that the Eccles Building, the mothership of the Federal Reserve System, is built on sand.

Rudd’s paper is neither hawkish nor dovish. Though some hawks seem hellbent on interpreting it that way. (Read footnote 2, please.2 That ain’t for the doves.) He’s also not critiquing the Fed’s new average inflation target. Note well, the new target—with '“average” inflation, current and past—is less dependent to measures of expectations or FOMC forecasts than in the past. That said, Fed officials are still leaning too hard on measures of inflation expectations to argue that inflation will come back down and to justify not raising interest rates now. Rudd’s saying, don’t lean on inflation expectations. And stop talking about them. No one likes to talk about inflation. Stick to studying actual inflation and the supply and the demand factors in the real world that are pushing it around right now.

I applaud Rudd for pointing out the dangers of monetary policy decisions that rely on inflation expectations. Fed officials are awful at forecasting. (See my post on the dot plot last week), and people ignore them. We all are awful forecasters, especially during times of crisis.

Wrapping Up

We are living with the highest inflation in decades—though the monthly pace is stepping down and the pandemic, which is the source of many supply chain bottlenecks and labor shortages, is slowly getting under control. And at the same time, the Fed is using a new, untested inflation strategy. The world is tough, and forecasting near impossible. Now is not the time to be using broken tools.

Yes, Rudd’s style was punchy for a current Fed staffer in public.3 But he got your attention. Didn’t he? He took out a metaphorical two by four and smashed it over the head of mainstream macro. I use that style sometimes too. Really people, it’s the only way the old guard might listen. Everyone in macroeconomics and in central banks need to listen and ask ourselves tough questions about inflation.

A sea change in macro requires a change. Let’s go.

Disclaimer: This post shares my impressions of Jeremy Rudd’s paper, not his. Likewise, the views in his paper are his, not the Fed’s. All that said, I worked with Jeremy for over a decade and know his work well. He is a top inflation forecaster at the Fed and a very witty person. He’s also a good friend and mentor, who helped me get through some very rough patches at the Fed. I am thrilled that more of you are meeting him now too.

In most macro models, these expectations are referred to, “rational expectations.” The meaning is a bit different than you might think. It simply means that people have beliefs about the future that are reasonable given how they think the world works, that is, what the rules of the game are. Their expectations may not turn out to be correct, but that doesn’t mean they were irrational. “Perfect foresight” is stronger version of expectations and it means you got the crystal ball. Finally, a variety of models allow for more squishy expectation—a range from no expectations (one day at a time) or expectations that are kind of messed up, largely because people don’t put the time and energy into paying attention to everything in our ever changing world. Seems fair and I wrote a FEDS Note on that.

Footnote 2 from Rudd’s paper, “I leave aside the deeper concern that the primary role of mainstream economics in our society is to provide an apologetics for a criminally oppressive, unsustainable, and unjust social order.” See also my macromom blog posts “economics is a disgrace” and “economics truly is a disgrace.”

Several people expressed shock that the Fed allowed Rudd’s paper to be published. I was not surprised. FEDS Working Papers are the author’s view. Every one of the papers has the same disclaimer. The internal review process is to check for quality not police opinions. (NBER should add a quality check to its working papers too.) I don’t know but I suspect his last section on monetary policy was intentionally more vague than the rest of the paper. Why? Staffers are not there to tell policymakers what to do. They are are there to give them the best possible advice. It’s a fine line, and Rudd dances along it well. Finally, an oddity of the Board is that the easiest way to get your own, not the staff’s consensus views, to the Board is to publish it in public. That’s why I proposed and pushed hard for FEDS Notes. I wanted the Board to read more of the analysis by economists on the staff. The substance of most of my notes were ‘born’ many months, sometimes years before they showed up in public. So much good analysis is inside the Fed. Let’s share it with world.

This is good - I found your substack through your awesome tweet thread about Rudd's paper. I'm a total outsider (former philosopher, interested in economics but not trained) and am curious why we would be so quick to dismiss either the importance of inflation expectations in influencing price levels or the Fed's role in influencing inflation expectations.

In principle, it seems like (1) people use inflation expectations to bargain all the time. Whether or not they succeed in actually getting higher wages has more to do with labor's relative power at a given time than their inflation expectations though. And (2) it seems like the Fed could definitely influence peoples' inflation expectations through its rate targeting stance; but again, whether it succeeds in actually manifesting this influence is another story.

But more importantly, I'm not so clear on why that should matter. Surely the Fed has tons of other tools in the toolbox to manage price levels. I think the real worry is that they don't know which tools are working, and why, and whether it's actually their behavior that keeps price levels behaving like they do and not factors beyond their control.

So maybe the worry is just that it's another crack in the glass of classical theories> Either way, I'd love to see more debate about whether and when we've ever been operating at economic capacity and some discussion about reverse hysteresis and the role that public spending has to play in boosting output in the longrun. But again, total rookie here.

If you can't measure it don't talk about it, whether inflation expectations, rational expectations or animal spirits:. https://rwer.wordpress.com/2021/09/13/maybe-inflation-should-be-welcomed/