The "sufficiently restrictive" Fed. Part 1: The labor market

Fed officials will eventually decide that they have raised interest rates enough. How they make that call is of great importance, and the Fed should share its thinking.

The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time. In determining the extent of future increases in the target range, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.

~ FOMC Statement on February 1, 2023.

What does “sufficiently restrictive” mean? The Fed’s definition will influence how many workers have jobs and how long inflation remains high.1 It’s not enough for Fed officials to tell us what the so-called terminal rate—the peak federal funds rate—might be. Tell us why. Define “sufficiently restrictive” in plain English.

Today’s post on the labor market is the first in a three-part series. that unpacks the FOMC’s guidance on “sufficiently restrictive” interest rates. (The other two posts are on inflation and profits.) It’s an essential exercise. My knowledge of how Fed staff interprets data and forecasts gives me an advantage, but even I am baffled by some of their current messaging. If others are baffled too, that’s a problem. Now more than ever, the Fed needs a robust external debate. Fed officials will decide interest rates, but they would benefit from a wide range of opinions. These decisions are too important to limit to only internal debate, which runs the risk of groupthink.

What does the labor market look like when it’s no longer “extremely tight?”

Despite the slowdown in growth, the labor market remains extremely tight, with the unemployment rate at a 50-year low, job vacancies still very high, and wage growth elevated. Job gains have been robust, with employment rising by an average of 247,000 jobs per month over the last three months. Although the pace of job gains has slowed over the course of the past year and nominal wage growth has shown some signs of easing, the labor market continues to be out of balance. Labor demand substantially exceeds the supply of available workers, and the labor force participation rate has changed little from a year ago.

~ FOMC Statement on February 1, 2023.

Conditions in the labor market are central to the Fed’s thinking on “sufficiently restrictive.” What’s less clear is what it’s looking for and the logic behind its thinking. That’s a problem, given the high stakes for workers and businesses.

The Fed has told us the variables it focuses on: the unemployment rate, vacancies, job gains, wage growth, and labor force participation. But the Fed should be more specific, especially given the unusually large mixed signals from the labor market and the lingering disruptions from the pandemic. Moreover, the Fed must defend its assessment of an “extremely tight” labor market and explain why that’s not changed even as the labor market normalizes. Let’s unpack the FOMC statement above.

“Despite the slowdown in growth, the labor market remains extremely tight…”

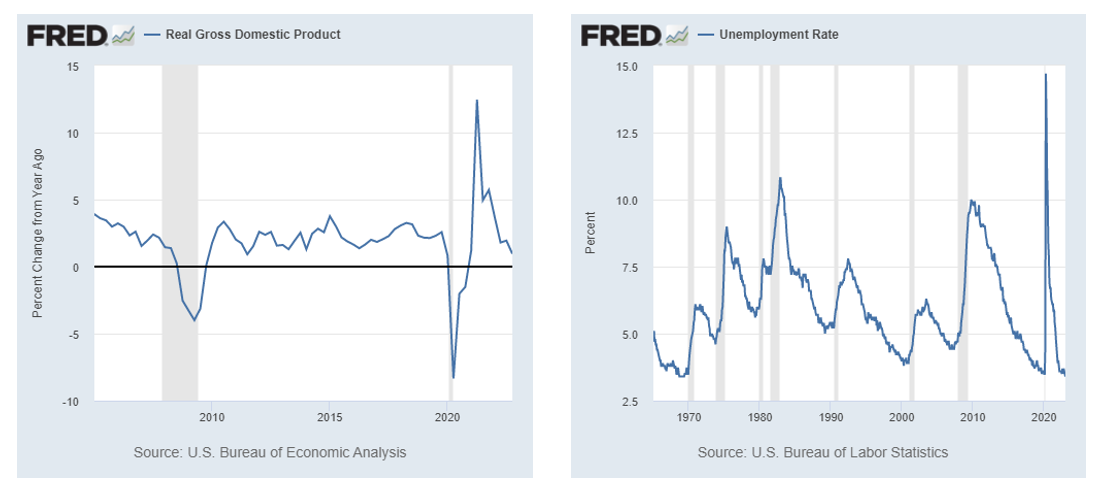

There is considerable tension and importance in those words. The degree of “tightness” (or its opposite: “slack”) describes how close an economy is to operating at its sustainable capacity. Exceeding capacity will push up inflation, and falling below capacity will push inflation down. The standard metrics—GDP (output) and unemployment (the labor market)—are not sending the same signal right now. Real GDP growth has slowed to below trend, suggesting slack, and unemployment is at a fifty-year low, suggesting tightness—two very different pictures.

Slack in output (not the Fed's words) with an extremely tight labor market (the Fed's words) is unusual, and that suggests that something may be amiss in the Fed’s assessment of the labor market.2 And that tension, depending on how it's resolved, could lead to incorrect guidance on inflation risks and what the economy needs to look like for the Fed's rate increases to be sufficiently restrictive.

Writing off GDP and focusing solely on the labor market to determine when the Fed has done enough is problematic and could easily lead to the Fed doing too much. How does demand (GDP) slow notably while the labor market remains hot? It seems unlikely. Remember those lags in monetary policy: if the Fed is waiting for the unemployment rate to rise notably, it will likely wait too long to ease up. It's risky to peg interest rate policy to the labor market alone.

Job gains have been robust, with employment rising by an average of 247,000 jobs per month over the last three months.

“Robust” in Fedspeak is well above average. (Yes, the Fed has a hierarchy of adjectives.) But 247,000 jobs per month (through December) is close to the average of nearly 200,000 in the five years before the pandemic.3 Somewhat above average is “solid,” not robust. And solid is not what one would pair with “extremely tight.”

Most importantly, when we have a labor shortage, we want more jobs filled. New jobs reduce the mismatch in the supply and demand for workers. As I’ve written before, the best way to solve a labor shortage is with more workers, not fewer customers. The Fed can only drive customers away with interest rate hikes, but the Fed raising rates is not the only path to restoring balance in the labor market and bringing inflation down.

To be fair to the Fed, there are ways that one can look at payroll gains and say that they are inflationary. People spend paychecks, so more paychecks could bring more customers and limit the price sensitivity of consumers. But that’s not about a tight labor market; that’s about income and demand. If that’s its thinking, then say it.

“ … with the unemployment rate at a 50-year low, job vacancies still very high, and wage growth elevated.”

Turn back the clock to the last FOMC meeting before Covid in January 2020. The unemployment rate was 3.5%, and the three-month average of payroll gains was 217,000. The FOMC statement described payrolls as “solid” and the labor market as “strong,” not “extremely tight.” There are differences between now and then, like lower overall labor force participation, substantially more job openings, an elevated quits rate, and higher wage growth. But do these differences, especially as the indicators improve, justify calling the labor market “extremely tight” versus “strong”?

Again, the Fed’s characterization of the labor market is glossing over key features of the economy now, specifically imbalances from the pandemic. Less than two months after the FOMC met in January 2020, we shut the U.S. economy down, and other countries worldwide did too. The lesson of the past three years is that shutting it all down is extremely disruptive. It’s not hard to lay off millions of workers within weeks, but it is hard to hire them back later, especially after you've shut down the borders and over a million Americans died from Covid, and even more, have long Covid. The labor market is not extremely tight, it’s healing, and that takes time.

The number of imbalances caused by Covid and the war in Ukraine is numerous:

The imbalance due to disruptions in the labor market differs from the Fed’s characterization of imbalance: “the labor market continues to be out of balance. Labor demand substantially exceeds the supply of available workers.” This one is about sectors and adjustments that complicate assessments of the overall labor market.

Wage growth shows the sectoral imbalances and how they are slowly unwinding. In the summer of 2021, labor shortages were acute, and at the same time, wage gains, especially for low-wage service workers, spiked and remained elevated until the fourth quarter of last year. Wage growth in those sectors is now close to its pre-Covid pace.

For the overall economy, wage growth was 4.1% in the fourth quarter, coming down near the range of 3% to 3.5% that the Fed views as not being inflationary. Indeed, inflation in core services, excluding housing, remains elevated, but labor cost growth in that sector is slowing considerably, which sets a path toward lower inflation even if it’s not as fast as we would like. Slow rebalancing is not limited to services. As Chair Powell said at the last press conference about the recent goods disinflation:

So we, of course, expected goods inflation to start coming down by the end of 2021 and it didn't come down all through '22. And now it's coming down, and it's come down pretty fast.

It’s not surprising that inflation in the service sector is taking longer to come down. It wasn’t until last year that we saw a clear shift back to services from goods, and we are still working through pent-up demand for services like vacations that people missed out on during the pandemic. The sectoral imbalances should clearly indicate that diagnosing the labor market is problematic if we focus on aggregates. And patience is called for. Extreme disruption should not be mistaken for extreme tightness.

The Fed’s Phillips Curve

The only metric of the labor market that has shown no improvement—as defined by the Fed—is the unemployment rate, which is now 3.4%. In their most recent forecast in December, the median forecast of the Fed officials said that under “appropriate” monetary policy, the unemployment would be 4.6% in the fourth quarter of this year and remain there throughout 2024.4 That would be more than a one percentage point increase this year. It would be unprecedented (though not impossible) to have the unemployment rate rise that much in one year and then hold at that level. In the past, when unemployment starts rising, even half that amount, it keeps going. Each percentage point is 1.7 million unemployed workers. Getting this wrong is a big deal.

If the Fed will not rest until unemployment is over 4%, then it should say so. And then we should discuss it. I am not going to rehash my deep concerns with using the Phillips Curve and guesses at the natural rate of unemployment.

Instead, I will bring in John Roberts, a former senior staffer at the Fed and expert on FRB/US, the Fed’s workhorse forecasting model. John’s blog is excellent. Among many valuable contributions, he’s been deciphering the forecasts from Fed officials. Here’s one bit on how the Fed’s thinking about the Phillips Curve shifted in September:

In the September SEP, the unemployment rate is projected to exceed the FOMC’s estimate of its longer-run value to a notable extent: It reaches 4.4 percent by the end of next year, higher than the 4.0 percent longer-run value (throughout, I refer to the median projections from the SEP). In my previous posts, I had assumed that fluctuations in the unemployment rate had very little effect on inflation, consistent with the experience of recent decades. But in that case, there would be little benefit in terms of inflation reduction from an overshoot of the unemployment rate, as the FOMC has assumed in this projection. So this time, I modify the model to allow for a substantially larger effect of the unemployment rate on inflation—that is, a steeper Phillips curve. Along with the assumption that the unemployment rate needed to stabilize inflation is temporarily elevated, the FOMC would have a motive to allow the unemployment rate to overshoot its longer-run, as in the September SEP.

The tradeoff between inflation and unemployment may have gotten more pronounced; Roberts has a compelling post on that point. But it’s possible that it has not. We don’t know. And that is my main concern with the Phillips Curve. First, we assume there’s no relationship between unemployment and inflation, that is, a flat Phillips Curve. And then bam, the curve is steep, and we are high on it. I eagerly await the shape of the Phillips Curve that explains disinflation and the unchanged, very low unemployment rate. None of this confusion is a surprise, especially now. Research has long told us that the Phillips Curve is problematic when inflation is also affected by supply shocks, as it is now.

In closing

Millions of jobs are on the line.

The Fed must explain how the labor market fits into its assessment of “sufficiently restrictive” interest rates and why it sees the labor market as“extremely tight.” Yes, it’s complicated, given the mixed signals across indicators, the recent improvements, and ongoing disruptions from the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Knowing what the Fed is looking for is the starting point for a productive and urgent discussion.

The Fed “influences” but does not unilaterally “control” the economy. Its influence is a powerful one, but it is not all-powerful. Treating the Fed as all-powerful is a big mistake.

Though I disagree with this logic alone, there is a way to square this circle. In macroeconomic models, tightness is judged by 1) GDP minus potential output (y-star) and 2) unemployment rate minus the natural rate of unemployment (u-star). Both subtracted variables are judgmentally set with some guidance from data. The staff has lowered its estimate of potential output to reduce the slack in output and raised its estimate of the natural rate of unemployment to create more tightness. Those changes are in response to high inflation and better align output and labor market with extreme tightness. One can tell stories about lower productivity growth and labor force participation to justify these changes in potential output and the natural rate of unemployment. However, it’s still a bit of a sleight of hand and glosses over the discussion we should have about the tension between output and the labor market now.

The 517,000 payrolls in January would bring that 3-month average to 356,000, which would merit a “strong” or maybe even “robust” label. Note January could revise, and revisions have been substantial during this recovery. Also, Dan Wilson, an economist at the San Francisco Fed, estimates that 128,000 of the new jobs in January were due to unseasonably warm weather, as opposed to strong underlying demand. It will also be important to see the next few months of data to see if this is an aberration or the start of a pickup again in jobs. When the Fed meets in March, it will have the January, February, and March jobs report.

Fed officials will provide their updated forecasts at the March meeting.

I agree. The Fed is an “independent” department that should be more transparent and communicate clearly so that the public can understand its rationale. Instead, we get plain-spoken comments from the Minneapolis Fed Governor such as how he’s “going to teach Wall Street a hard lesson.” That strikes me as in productive, as well as an expression of ego.

We have a solution to the coming long-term shortage of labor:

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2022.html

The U.S., far and away, imprisons a higher percentage of its people when compared to other advanced economies. Instead of complaining about a lack of workers or qualified workers, prisoners who pose no threat to society should be treated for behavioral problems and trained for employment that best fits their aptitude. The amount of money spent to imprison people is far greater than releasing them into a system of counseling and skills training. I’ve hired and worked with former felons. Many are smart and hard-working. People on a variety of spectrums (e.g., ADD, Asperger’s, Autism) have been hired and trained to work in all levels of employment. The shortage of legitimate labor required to keep growing the economy exists in the prison system -- and we’re paying through the teeth to keep it there?

I had just shared this article on Twitter and yes I agree that the fed could be more transparent regarding rate hikes, but you also have to give the jobs market some credit for solid job growth despite the aggressive rate hikes from the federal reserve. I also agree with one of your previous articles from before in which if you want to solve this so-called shortage of workers then you solve it with labor, not rate hikes. Better pay, more benefits, and hours would go a long way towards bringing those workers back, especially since so many have left due to covid. I'm excited to read parts two and three coming up.