The Child Tax Credit will transform our economy

Sending money to nearly all families every month, regardless of whether the parents work, is a fundamental change in how we support our children. It will affect all Americans and economic activity.

Congress continues to debate legislation that will invest in our infrastructure and our people.1 These policies would begin a long-overdue transformation of our economy. It’s essential to make every dollar count, and I take Senator Joe Manchin at his word:

“I’m open to supporting a final bill that helps move our country forward,” he said at an afternoon press conference. “But I’m equally open to voting against a bill that hurts our country.”

I agree. Policymakers must use this opportunity to move our country forward. As an economic policy adviser, it’s my job to explain the potential effects—good and bad—of policies and suggest the best ways to make forward progress.

‘Cash for Kids’ with the Child Tax Credit

Extending the new Child Tax Credit (or Cash for Kids) is the policy with the highest potential benefits for the country. Even so, it has potential costs beyond its price tag, and policymakers need to hear about those risks too.

Research, pilot studies, experiences in other countries, and data show that the effect of cash transfers on families and children is likely to be positive. See my recent post:

I urge Congress to center its efforts on children. It would be the ‘biggest bang for the buck,’ supporting families now and investing in our next generation. Done well, it would lift long-run economic growth, benefiting all Americans. It’s a moral imperative too. The richest country in the world should not have children living in poverty. Finally, it’s about dignity. Helping families is empowering them.

Given its size and breadth, the effects of the Child Tax Credit will go beyond the families and children who receive them. People who do not receive the credit, businesses, and communities are also likely to experience the feedback loops.

Effects on the overall economy

In a recent report for the Jain Family Institute, Stephen Nuñez, Sidhya Balakrishnan, and I discuss cutting-edge research on the long-term macroeconomic effects of the Child Tax Credit (and guaranteed income programs). The Manchin metric of “moving our country forward” requires us to think through the effects on everyone and the overall economy.

Here is a 15-minute talk on the findings and critical considerations from this research:

Disagreement is healthy

We do not draw firm conclusions on what the macroeconomic effects would likely be. The research is not as clear-cut as the microeconomic studies of the effects on recipients. The predicted effect on long-run GDP—one of many overall measures we should consider—ranges from positive to negative.

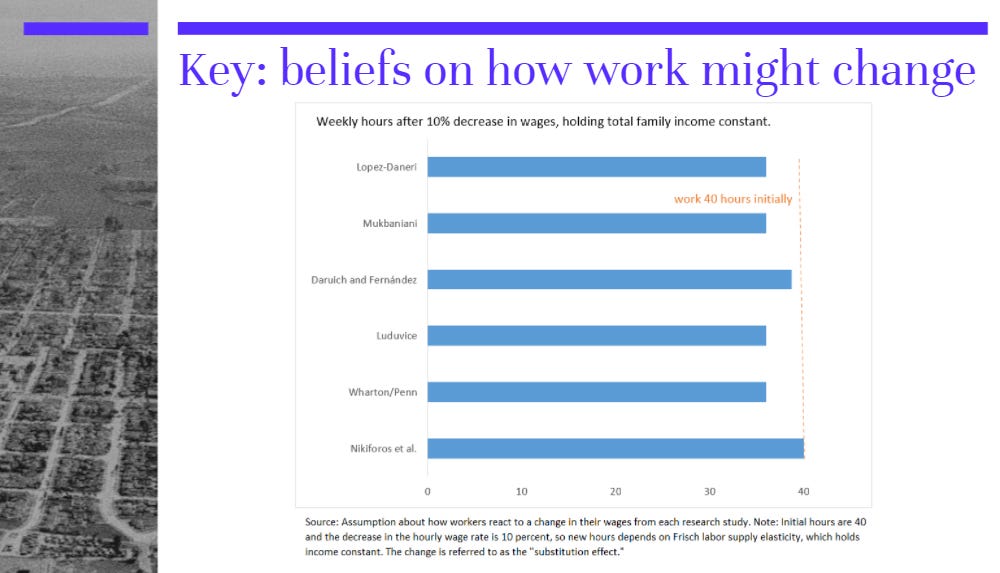

Our report focuses on why the researchers come to such different conclusions. Without a doubt, the most crucial question is how much a guaranteed source of monthly income would change how much parents work, and over time how changes in after-tax wages might change how much everyone works. A wonky assumption called the “Frisch Labor Supply Elasticity” is at the core of all these models, and there’s no consensus on its value, as we show here.

The potential effects on savings and business investment could also feed through to overall economic activity. Once again, studies vary.

Divergent opinions are not a reason to dismiss the macroeconomic research. Before Congress enacts the policy, it should consider feedback loops and possible unintended consequences. It is also an opportunity to pair the Child Tax Credit with other policies that could counteract potential weaknesses in the program.

No single policy can move our country forward. We need a set of policies to invest in our people in which the sum is greater than the parts.

Many effects to consider with the Child Tax Credit

My colleagues at the Jain Family Institute have written several other reports and issue briefs on the guaranteed income that are relevant to the policy debates about the Child Tax Credit. Here is one finding, quantifying the tradeoffs between poverty reductions and budget cost. Do not add a work requirement!2

Wrapping up

As members of Congress deliberate on extending the Child Tax credit and making several other investments in our people, they must consider the potential long-term consequences of the program on the economy. The existing macroeconomic research on cash transfer programs is not clear-cut. Still, it provides insights on the central pathways by which the Child Tax Credit could affect the larger economy. Our report unpacks why the models disagree, so policymakers can assess the assumptions in the studies and consider the feedback loops the program might cause.

Please consider financially supporting my Substack with a paid subscription. You will help me to write regularly about economics here, and you will receive some paid-subscriber-only posts.

I am adamant that the White House must better explain to the public why these two large packages are important. Play offense and listen to the people. Let’s start with names. Investments in people or ‘kids, care, climate’ legislation would be an improvement. I refuse to call the plan ‘Build Back Better’ or the reconciliation bill. No wonder it’s gotten political using Biden’s campaign slogan. Half the country is shouting, “Let’s go, Brandon.” Most people have no idea what’s in the package. Let whoever came up with Coronavirus, Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act name this bill. Explain it. Sell it—words matter.

Many arguments exist against a work requirement (or a phase-in of the credit by income). First, as the analysis shows, the poverty reduction is much smaller. Second, it dramatically increases the administrative burden on the program. Finally, it would lead to fewer families receiving the monthly cash transfers when unemployment rises, at a time when families need the most support.

It s important that the positive effect of the investment not be undermined by failing to pay for it with taxes. If it adds to the structural deficit, we will just be shifting from one kind of investment (what is financed through the capital markets) to the investment in CTC. It might still be worth doing, but deficit financing would make it marginal.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. Your footnote is an important one “ I am adamant that the White House must better explain to the public why these two large packages are important. Play offense and listen to the people. Let’s start with names.” I would like to see the same. It was a big part of discussion in class today.