Burden of proof is on the inflation hawks now

Reality shows a "soft landing" in 2023 in the United States taking shape. We avoid a recession, we keep the job-full recovery, and inflation moves back down. Hawks, it's time to join us in reality.

Getty Images.

This week was very good.

Day after day this week, week after week for months, the developments in the world, the economic data, and guidance from the Fed raised the likelihood of a “soft landing” next year. Among those experts grounded in reality, the profound pessimism from early this year is shifting to cautious optimism, moving us toward our ultimate goal: plentiful jobs with good pay and low inflation. Keep fighting.

Finally, going into 2023, we are on track for a more stable world where we live more safely with the pandemic, have an energy supply and trade less dependent on dictators. And Putin is out of Ukraine forever.

What’s the case for a soft landing in the U.S. economy?

Inflation is moving down; more relief is on the horizon.

This week the data on Personal Consumption Expenditure Prices (PCE) inflation was lower than expected.1 Excluding food and energy, referred to as core inflation, was only 2.6% at an annualized rate in October, far below its peak of 7.5% in June.

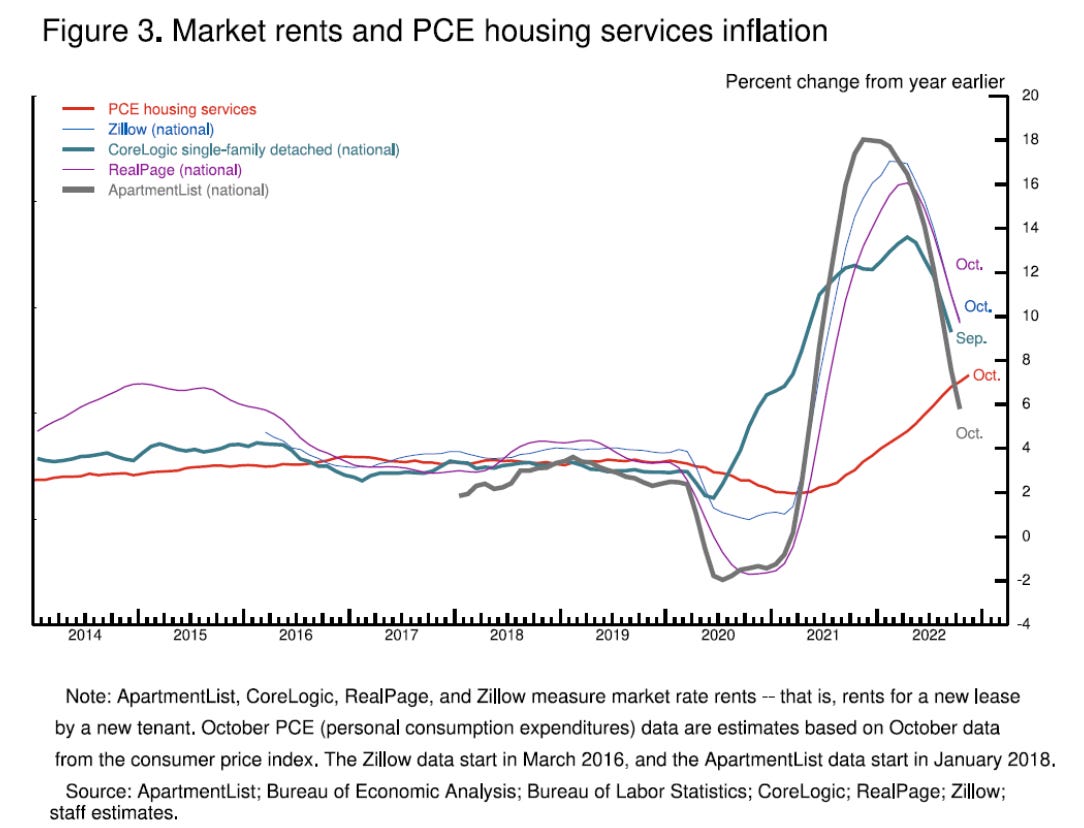

Inflation remains a wild ride. Even so, encouragingly, inflation is moving down. The average rate of PCE core inflation from July to October was 3.9% versus 5.0% in the first half of this year. That step down owes largely to disruptions due to Covid easing, pent-up demand subsiding, and the end of fiscal stimulus. The full effect of the Fed’s interest rate increases is next year. In addition, the most recent, large declines in rental prices will show up next year in the official measures of housing costs, pushing inflation down considerably. Good!

In addition, for months, producer price inflation has decreased, and import prices and transport costs are falling. These developments will show up in consumer inflation. I am frustrated that after the mounting good news that I am still reading gloomy takes. Even from people like Matthew Klein, with whom I agree more than 85% of the time. Not today, not at all:

I want to believe that there is still a path to “immaculate disinflation”, with job market churn fading in the context of rising employment and rising living standards for all. But it is getting harder to see how it happens. Tolerating persistent inflation of 4-5% may be a bitter pill for many policymakers, but may be better than many of the alternatives. At least right now most people still have jobs and real consumer spending is still rising on trend.

Disinflation isn’t “immaculate.” We don’t need heaven; we need 2% inflation.

The Fed is not swallowing a “bitter pill” of a higher inflation target. The Fed will bring PCE inflation back to 2% come hell or high water. I don’t think it will have to burn us to a crisp or drown us, but the Fed will if inflation stalls out above 2%. Olivier Blanchard and others are wrong. The Fed should not raise the target to 3% or 4%. I know the Fed; I know the FOMC. The Fed will NOT raise the target. I agree with former New York Fed President Bill Dudley here:

Moving to a higher target before the Fed gets inflation back to 2% would undercut the central bank’s credibility. Moving the goal posts would be interpreted as a failure, making it more difficult to anchor expectations around the new objective. After all, if the Fed is willing to change the target once, why believe it won’t change it again?

The Fed is knowingly risking a severe global recession, is making it more costly to fight for democracy in Ukraine, causing a hunger crisis in the Global South, and destabilizing financial markets all in the name of its credibility as an inflation fighter. The Fed is NOT backing down. (Unless Congress tells them to, as I argue here.)

Very good news: Fed is losing its ‘war on workers.’

Jobs: on Friday, we learned that we added 263,000 jobs, on net, in November. That’s somewhat above the consensus forecast and the pre-Covid average. The gains were widespread, welcome, the very good news. And as I have argued for months, the best way to solve labor shortages is with more labor, not fewer customers. Keep going.

During 2022 so far, we have averaged almost 400,000 more jobs per month, and that’s on top of the 500,000 average monthly jobs in 2021. That’s a job-full recovery!

Earlier in the week, the Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) confirmed easing in the labor market; job openings and quit rates are down some. The historic highs came with very high wage growth and the most difficulties for businesses.

Jobs openings and quits are way above the pre-Covid levels. A job posting coming down is much better than a pink slip going out. Workers still have the upper hand. It’s long past time to give workers living wages and promising career paths. Share buybacks and millions in bonuses can wait.

Wages: Ongoing, solid wage growth, particularly with higher inflation this year, is a godsend, not a ‘dashing of hopes.’ The link between wage growth and inflation was unclear before Covid, and nothing in aggregate data suggests it exists now. Just because macroeconomic theory says they move together does not mean they do.

Expert economists on inflation know that solid wage growth does not doom us to high persistently high inflation. Research from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in November 2022 investigates the possibility of a wage-price spiral. (Note, inflation is moving down, so you would need some a spiral to reverse that dynamic.) It is unlikely.

How often have wage-price spirals occurred, and what has happened in their aftermath? We investigate this by creating a database of past wage-price spirals among a wide set of advanced economies going back to the 1960s. We define a wage-price spiral as an episode where at least three out of four consecutive quarters saw accelerating consumer prices and rising nominal wages. Perhaps surprisingly, only a small minority of such episodes were followed by sustained acceleration in wages and prices. Instead, inflation and nominal wage growth tended to stabilize, leaving real wage growth broadly unchanged. A decomposition of wage dynamics using a wage Phillips curve suggests that nominal wage growth normally stabilizes at levels that are consistent with observed inflation and labor market tightness. When focusing on episodes that mimic the recent pattern of falling real wages and tightening labor markets, declining inflation and nominal wage growth increases tended to follow – thus allowing real wages to catch up. We conclude that an acceleration of nominal wages should not necessarily be seen as a sign that a wage-price spiral is taking hold.

The IMF is a well-respected, non-partisan institution full of economists with deep expertise in economic conditions. They’re not radical left-wing economists. They’re not freaking out, nor should we.

Again, there is no consensus (not even close) in cutting-edge, peer-reviewed empirical research finding a solid link between wage growth and inflation. Sure, our theoretical models say the connection is tight. That’s not good enough. If you are going to advise central bankers to tank the global economy, you must bring an ironclad case.

The burden of proof is on the hawks. I see no proof. None.

The Fed is slowing down.

What also made me optimistic this week? Fed Chair Jay Powell said very clearly this week; THE FED IS SLOWING DOWN.

Every 75 basis point hike in the fed funds rate this year had shaved percentage points off my soft-landing scenarios. No more. The Fed is finally leaving the 1970s and joining us in 2022. They are slowing down. That’s crucial for a soft landing.

I knew this was coming. Vice Chair Lael Brainard signaled a slowdown in October at the National Association of Business Economics annual meeting. Then this week, Brainard made a convincing case that inflation now is mainly due to Covid and Putin. Most importantly, she argued that the standard thinking on monetary policies in times of high inflation, like Volcker’s approach, is not applicable now.

Next to Powell, Brainard is the most critical voice at the Fed. She is a thought leader and someone whose counsel Powell relies on. So, not surprisingly, Powell confirmed this week the slowing Brainard made a case is the Fed’s plan.

Let’s dig in more. The Fed is data-driven and will get inflation back down to 2%. It studied the subatomic particles of inflation when everyone else ignored it pre-Covid under the false belief that the Fed controls inflation. Ricardo Trezzi2, a former inflation forecaster at the Fed, has a model similar to the Fed’s primary model of inflation. Good news this week:

As in CPI space, our Common-Idiocratic and Covid (CI-C) model estimates that net of Covid and idiosyncratic shocks, the strength of the data is softening. The model estimates that the 3m/3m (a.r.) of common component is the lowest in the last 17 months (see figure 4 below). We still have a long way to normalization because the level of the common component remains well above pre Covid but something is changing in the data and it seems the Fed is putting more weight than usual on the short-term signals.

The trend is very promising.

The hawks are the problem now. Stand down.

Now is the time, more than ever, for a robust debate about the economic outlook.

Policymakers, families, businesses, and communities are making decisions based on the views about next year. Will inflation remain high? Will the U.S. enter a recession? Will they lose their jobs? Will they lose their customers? And so on.

People look to macroeconomists for answers. With the steady stream of more optimistic data on inflation and a path to a soft landing taking form, it is time for the hawks to explain themselves.

Yes, most professional forecasters and I expected inflation to be back down by now; I was Team Transitory. I was wrong. Why? Covid was not transitory. This time last year, we were rolling from the horror of delta into Omicron, killing millions. And only months later, Putin invaded Ukraine and sent food and energy prices skyrocketing. None of the inflation hawks in March 2021 talked about Covid variants or Putin. They still don’t. They were wrong about why inflation shot up and lasted as long as it did.

Being right for the wrong reason makes someone dangerous.

More importantly, the inflation hawks were wrong that we needed high unemployment and low wage growth to slow inflation. Larry Summer said we needed unemployment up to at least 6%, incorrectly using the Phillips Curve. He has repeated such dire predictions. Larry is still saying it. Come on, look around.

WE DO NOT NEED TO CRUSH WORKERS TO GET INFLATION DOWN. We do not. Inflation is turning, and unemployment is very low. The labor market, on most measures, is more robust and pro-worker than it was even before Covid. GOOD!

We did not and do not need a recession. We do not need the Fed to cause one.

I did not revise my inflation forecast on the wage data—no reason to. I did revise it favorably on the PCE inflation data this week. On the jobs day, I favorably revised my forecast for a soft landing even more. Solid wage growth will provide income to buffer families, especially those with little savings, when the full effect of the Fed rate hikes comes next year. Consumer spending is almost 70% of the U.S. economy; income is the biggest driver of spending, and the largest source of income is paychecks. Inflation is coming down, and workers are doing well. That is the only path to a soft landing, which is increasingly likely. That’s the best news of all!

Finally, the highest cost of the hawks is not the Fed doing too much. It’s our future. If we listen to the hawks now, we will wreck our ability to build a more resilient, productive economy. Thursday, I spoke to a group of individuals who serve on the Board of Directors of Fortune 500 companies across sectors, including energy and technology. One warned that many CEOs are listening to the doomsayers and pulling back on capital investments. We need capital investments to protect us from future inflation, fight climate change, and improve our infrastructure. What are you doing?

There’s a better way. Isabella Weber’s new research with colleagues explains why targeted efforts are required. The Fed’s tools in monetary policy are not targeted.

The world needs sound economic advice.

Wrapping up.

The past year proved the doves wrong; inflation is still high, albeit stepping down. It also proved the hawks wrong; we did not need a recession to turn inflation down.

Good macroeconomists update their outlook as we learn more about the world. Since the pandemic began, we have seen that from the Fed. Its optimism in 2021 shifted to pessimism in 2022, and as we enter 2023, it is shifting back to optimism again. Correct.

Given all we learned recently, the inflation hawks must explain why they remain so pessimistic. Put the best current arguments on the table and judge them on merit.

I have seen nothing from the hawks to sway me. Nothing. And I am looking. Being wrong about inflation crushed me this spring. I set an even higher bar to become optimistic again. This week decisively pushed me over the bar. We are not out of the woods, and I do not expect a soft landing to be here until well into next year. If it comes, I will not do a victory dance on the graves dug in the past three years. I will be profoundly relieved and grateful. We all will be.

If you enjoyed today’s post, please subscribe. In addition, a paid subscription allows me to continue writing here and pursue my policy work as a self-employed economist. I will write a post later this week on Chair Powell’s speech tomorrow, largely for paid subscribers.

Personal disposable income, after inflation, increased by 0.4% in October. Consumer spending rose 0.5%. That’s very good. That’s so important to families and small businesses.

More than any private inflation forecaster, you should follow Ricardo Trezzi. After leaving the Fed, he founded Underlying Inflation Consulting.

Hi, a question on the inflation target. Going forward inflation may get structurally higher and volatile due to factors largely beyond the Fed's control (commodity, trade, supply chains, etc.). Wouldn't keeping the 2% target induce a structural contractionary bias to monetary policy? In this sense a higher target would make sense, and maybe would not harm the CB's credibility, not to mention the positive effect on debt dynamics. In other words, one could say that the 2% target was good for the world we saw in the 90s/00s but may not be fit for the 2020s. Thanks.

What are your thoughts on inflation being sticky? The higher end of inflation is easier to tame, but the closer we get to 2, the stickier inflation becomes. We are still estimated to be ABOVE 7 percent. Progress is great, but the job isn't close to being finished.

Thanks for the awesome post! Interested to hear your thoughts.