Inflation due to Covid and war in Ukraine shows us the limits of monetary policy

Yesterday, Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard gave a speech, "What Can We Learn from the Pandemic and the War about Supply Shocks, Inflation, and Monetary Policy?" It starts an important conversation.

In today’s post, I discuss the speech by Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard on what the pandemic and the war in Ukraine are teaching us about persistent, supply-driven inflation and the challenges for monetary policy. I reproduce much of the text, charts, and footnotes. See the full version on the Fed’s website here.

Source: Getty Images.

Lessons now will inform future economic policy.

From the start of her speech, Brainard centers on what Covid and Putin have taught us about the vulnerabilities and rigidities in the economy's supply side. And how that raises important questions about monetary policy.

Policymakers and researchers have begun reassessing certain features of the economy and monetary policy in light of recent experience. After several decades in which supply was highly elastic and inflation was low and relatively stable, a series of supply shocks associated with the pandemic and Russia's war against Ukraine have contributed to high inflation, in combination with a very rapid recovery in demand. The experience with the pandemic and the war highlights the challenges for monetary policy in responding to a protracted series of adverse supply shocks. In addition, to the extent that the lower elasticity of supply we have seen recently could become more common due to challenges such as demographics, deglobalization, and climate change, it could herald a shift to an environment characterized by more volatile inflation compared with the preceding few decades.1

Brainard rightly sees an urgency to this conversation. We are struggling with two tragic events that led to massive global disruptions to supply. The list of other possible, near-inevitable ones is long. We must build new tools and new thinking.

Covid and Putin are the roots of all evil now.

In her speech, Brainard says "pandemic" thirty times; mentions of “war” and “Ukraine” are numerous too. It’s heartening to finally see a high-ranking Fed official so forcefully identify the primary causes of high inflation today.

Inflation in the United States and many countries around the world is very high (figure 1). While both demand and supply are contributing to high inflation, it is the relative inelasticity of supply in key sectors that most clearly distinguishes the pandemic- and war-affected period of the past three years from the preceding 30 years of the Great Moderation.2 Interestingly, inflation is broadly higher throughout much of the global economy, and even jurisdictions that began raising rates forcefully in 2021 have not stemmed the global inflationary tide.3

The American Rescue Plan and low interest rates in 2021 are not the roots of all evil.

It is November 2022. The pandemic and the war in Ukraine remain with us, threatening lives and livelihoods worldwide. It is extremely frustrating for macroeconomists to keep their narrow focus on those two policies last year. Yes, they contributed to the strong recovery in demand. That’s good, even if it came with temporarily high inflation! It’s a rebound in jobs, consumer spending, and investment tragically missing from the recovery from the Great Recession.

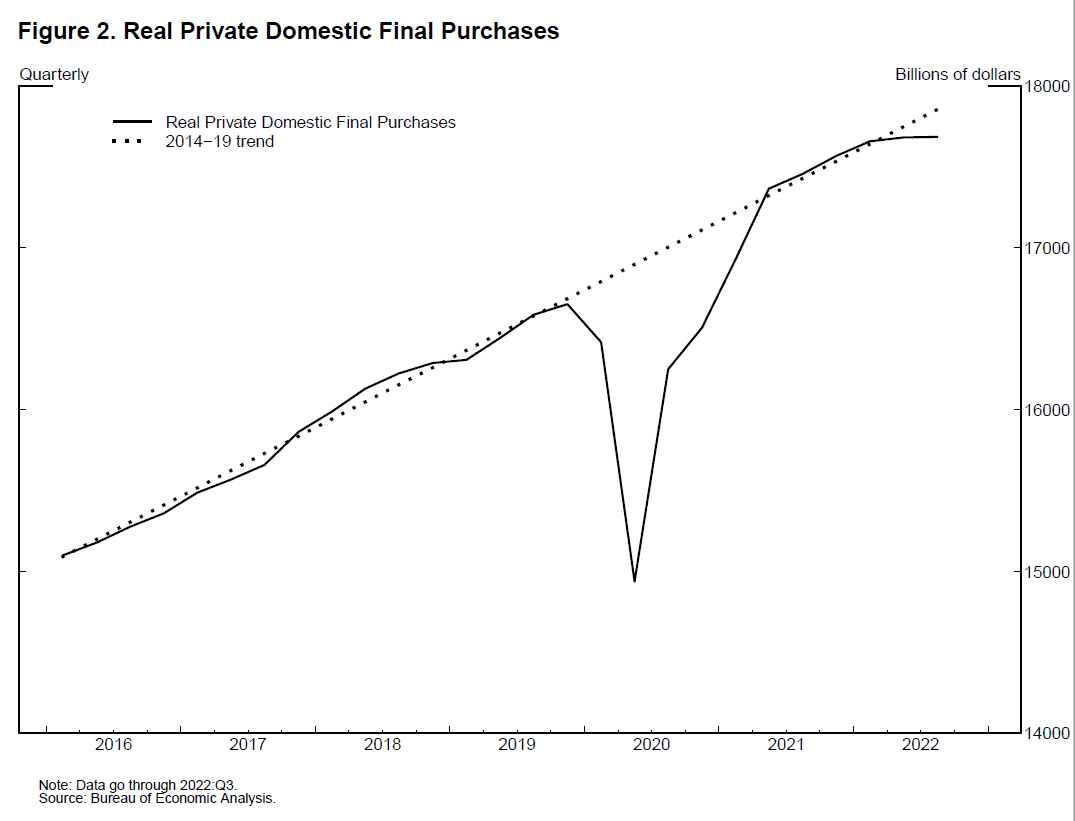

In the United States, as a result of significant fiscal and monetary support, the level of private domestic final purchases recovered extremely rapidly in 2020 and 2021 to levels consistent with the pre-pandemic trend before moving below trend in 2022 (figure 2).

In addition, as she does, we must recognize that these economic policies, especially the fiscal relief and pent-up demand, interacted with a Covid-caused abrupt shift to goods away from services, which were often restricted or unsafe due to the pandemic. And that put immense strain on supply.

Although demand came in near the pre-pandemic trend on an aggregate level, the pandemic induced a shift in composition that concentrated large increases in demand in certain sectors where the supply response was constrained. The shift in consumption from services to goods was so pronounced that—despite plunging at the onset of the pandemic in March 2020—real spending on goods had already risen nearly 4 percent above its pre-pandemic trend by June of that year. While a very slow rotation back toward pre-pandemic patterns of consumption has been under way for over a year, it remains incomplete more than two and a half years after the initial shutdown … (figure 3).

It’s been a wild ride, and it’s not over yet.

The month-to-month inflation readings have swung up and down. What else has? Our lives. Covid and its never-ending variants, Putin in Ukraine. That's hard on everyone.

The supply shocks to goods, labor, and commodities have been accompanied by unusually high volatility in monthly inflation readings since the beginning of the pandemic. Since March 2020, the standard deviation of month-over-month core inflation has been 0.22 percentage point—a level of variation not seen in a 31-month period since the 1970s and more than double the standard deviation in monthly core inflation from 1990 to 2019. ... The first burst occurred around reopening in the spring of 2021, and the second occurred amid the effects of the Delta and Omicron COVID-19 variants in the autumn of 2021 (figure 4).4

We were not prepared for major, long-lasting disruptions.

The main lesson from the past three years is that our economy is not resilient to such unexpected events. But it does not have to be that way. Imagine if we had previously invested in diversified supply chains; had universal health care, paid leave, and childcare; relied more on green energy, and had more competitive industries.

The evidence suggests that high concentrations of demand in sectors such as appliances, housing, and motor vehicles—where supply was constrained by the effects of the pandemic—played an important role initially in generating inflationary pressures. Acute constraints on shipping and on the supply of nonsubstitutable intermediate inputs like semiconductors were compounded by acute constraints on labor supply associated with the effects of the Delta and Omicron variants and later compounded further by sharp commodities supply shocks associated with Russia's war on Ukraine.

Old thinking on monetary policy was not up to the task.

As Brainard explains below, the standard thinking on monetary policy was not to react or to “look through” supply disruptions. Why? Because the tools of monetary policy (interest rates) do not fix supply problems. Hurricanes are a classic example of a disruption to supply. We expect FEMA, not the Fed, to step in. Expecting monetary policy alone to fix the current mess of supply-driven inflation is wrong.

The standard monetary policy prescription is to "look through" supply shocks, such as commodities price shocks or shutdowns of ports or semiconductor plants, that are not assessed to leave a lasting imprint on potential output.5In contrast, if supply shocks durably lower potential output such that the economy is operating above potential, monetary policy tightening is necessary to bring demand into alignment with the economy's reduced productive capacity. Importantly, and separately from the implications for potential output, monetary policy should respond strongly if supply shocks risk de-anchoring inflation expectations.6

Here is a crucial, only clear, in hindsight argument. Old thinking is not enough in the real world. One could point to countless examples in the past, but it’s glaringly obvious now. Kudos to Brainard here for saying it so clearly.

Although these tenets of monetary policy sound relatively straightforward in theory, they are challenging to assess and implement in practice. It is difficult to assess potential output and the output gap in real time, as has been extensively documented by research.77 This is especially true in an environment of high uncertainty. The level of uncertainty around the output gap varies considerably over time, and research suggests that more muted policy reactions are warranted when uncertainty about the output gap is high.8 The unexpectedly long-lasting global pandemic and the sharp disruptions to commodities associated with Russia's war against Ukraine have contributed to substantial uncertainty (figure 5).

Fine, but what the Fed is doing now is anything but “muted.” Brainard is the Vice Chair of the Fed, and her last two speeches, the prior one about international fragilities, have laid a path for the Fed to slow down. Unfortunately, many Reserve Bank Presidents are in the news daily, calling for more aggressive rate hikes.

Listen to Lael before it is too late.

The Fed is out of touch and out of balance.

Brainard highlights a theme that Fed Chair Powell and other officials have discussed extensively this year, “risk management.” According to the Fed, that principle justifies the aggressive rate hikes this year. It does not want to repeat the mistake of the Volcker Fed, which let up too soon and then caused another, deeper recession.

In addition, a protracted series of supply shocks associated with an extended period of high inflation—as with the pandemic and the war—risks pushing the inflation expectations of households and businesses above levels consistent with the central bank's long-run inflation objective.9 It is vital for monetary policy to keep inflation expectations anchored, because inflation expectations shape the behavior of households, businesses, and workers and enter directly into the inflation process. In the presence of a protracted series of supply shocks and high inflation, it is important for monetary policy to take a risk-management posture to avoid the risk of inflation expectations drifting above target.

What the Fed is doing now, which ignores the chance of doing too much, is not risk management. Risk management balances risks. All the Fed worries about is inflation expectations moving up permanently. If the Fed hikes too aggressively and destroys more demand than necessary to bring inflation down, which is increasingly likely, that could de-anchor expectations to the downside. That’s even harder to solve.

Monetary policy must change, and that’s far away.

I will leave the rest of Brainard’s speech for you to read. I disagree with her on key parts, underscoring how far monetary policy is from a reckoning. It is mindboggling that the Fed continues to obsess over inflation expectations when there is no evidence that they are de-anchoring. Surveys show that Americans remain 'Team Transitory.' Yes, the unelected, unaccountable people at the Fed calling the shots and elite macroeconomists have de-anchored. But they’re not representative of Americans.

Listen to the people.

Fiscal policy as a solution is completely missing. We must bring fiscal into the discussion, and it’s not here or in the elite macroeconomic discourse. The current crises are a wake-up call that resilience against inflationary pressures requires fiscal policy too. The Fed is not enough. Only Congress can take key steps, such as green energy investments in the Inflation Reduction Act and the onshoring programs in the CHIPS Act, to protect against spikes in future inflation.

In closing.

Lael Brainard’s speech marks the start of a sea change in monetary policy.

In the era of supply disruptions, it’s a conversation and a direction for research that we must embark on immediately. As the Vice Chair at the Fed, Brainard has a large megaphone, and I expect her to have an even larger one in the next few years. I am grateful that she is using it forefully. We should all be grateful.

To conclude, the experience with the pandemic and the war highlights challenges for monetary policy in responding to supply shocks. A protracted series of adverse supply shocks could persistently weigh on potential output or could risk pushing inflation expectations above target in ways that call for monetary policy to tighten for risk-management reasons. More speculatively, it is possible that longer-term changes—such as those associated with labor supply, deglobalization, and climate change—could reduce the elasticity of supply and increase inflation volatility into the future.

If you enjoyed today’s post, please subscribe. In addition, a paid subscription allows me to continue writing here and pursue my policy work as a self-employed economist. I will write a post later this week on Chair Powell’s speech tomorrow, largely for paid subscribers.

I am grateful to Kurt Lewis of the Federal Reserve Board for his assistance in preparing this text and to Kenneth Eva for preparing the figures. This text updates the views that I discussed as part of a panel at the BIS Annual Meeting on June 24, 2022. These views are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Open Market Committee.

Research has generated a range of estimates on the contributions from supply and demand factors. For example, Shapiro (2022) finds that demand factors are responsible for about one-third of the surge in inflation above the pre-pandemic trend, while di Giovanni and others (2022) find a number closer to two-thirds. See Adam Shapiro (2022), "How Much Do Supply and Demand Drive Inflation?" FRBSF Economic Letter 2022-15 (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, June); and Julian di Giovanni, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Alvaro Silva, and Muhammed Yildirim (2022), "Global Supply Chain Pressures, International Trade, and Inflation (PDF)," paper presented at the ECB Forum on Central Banking 2022, Sintra, Portugal, June 27–29.

The median year-to-date total policy rate hike within the group of Brazil, Hungary, New Zealand, Norway, Peru, Poland, and South Korea is 6 percentage points. All of these countries began forceful rate hikes in 2021, and the cumulative hikes have taken policy rates in some of these countries above 10 percent. Despite this, through September 2022 core inflation in these countries was 9.5 percent year-over-year, rising 3.5 percentage points since March. See Economist (2022), "Even Super-Tight Policy Is Not Bringing Down Inflation," October 28, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/10/23/even-super-tight-policy-is-not-bringing-down-inflation.

Pandemic fiscal measures played an important role in boosting demand, but the rapid deceleration of inflation over the summer of 2021 and subsequent rebound in inflation from October through the end of the year do not line up well with the fiscal demand impulse projected by most forecasters. For example, the Brookings Institution projected a smooth demand impulse from the American Rescue Plan that peaked at the end of last year. See Wendy Edelberg and Louise Sheiner (2021), "The Macroeconomic Implications of Biden's $1.9 Trillion Fiscal Package," Brookings Institution, Up Front (blog), January 28.

See, for instance, Martin Bodenstein, Christopher J. Erceg, and Luca Guerrieri (2008), "Optimal Monetary Policy with Distinct Core and Headline Inflation Rates," Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 55 (October), pp. S18–33, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304393208001050#!.

Ricardo Reis makes the case that both these factors would have prescribed tighter policy in the current environment. See Ricardo Reis (2022), "The Burst of High Inflation in 2021–22: How and Why Did We Get Here?" CEPR Discussion Paper Series DP17514 (London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, July)

See Athanasios Orphanides and Simon van Norden (2002), "The Unreliability of Output-Gap Estimates in Real Time," Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 84 (November), pp. 569–83.

For discussions of the time-varying nature of output gap uncertainty, see Travis J. Berge (2020), "Time-Varying Uncertainty of the Federal Reserve's Output Gap Estimate," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2020-012 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, February; revised April 2021); and Rochelle M. Edge and Jeremy B. Rudd (2016), "Real-Time Properties of the Federal Reserve's Output Gap," Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 98 (October), pp. 785–91. For a discussion of tempering the policy response to the output gap in response to increased uncertainty, see Athanasios Orphanides (2003), "Monetary Policy Evaluation with Noisy Information," Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 50 (April), pp. 605–31.

For two recent examples of assessing longer-term inflation expectations, see Michael T. Kiley (2022), "Anchored or Not: How Much Information Does 21st Century Data Contain on Inflation Dynamics?" Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2022-016 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March); and Danilo Cascaldi-Garcia, Francesca Loria, and David López-Salido (2022), "Is Trend Inflation at Risk of Becoming Unanchored? The Role of Inflation Expectations," FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March 31).

I realize this is against economic orthodoxy, but I find it insane that most believe the cure for “inflation” (i.e. higher prices) is for the Fed to raise prices. Raising the FFR raises the cost of funding, which forces companies to raise prices to maintain their margins. Interest expense is a real line item on any company’s income statement, and is also incorporated in higher storage costs for inventories. Huge CPG companies like PEP and Unilever reported double digit price increases in 3Q, despite declining sales volumes (i.e. demand). And an industrial production company that sells commodities on the forward or spot markets automatically raises prices for forward contracts when rates are higher, to incorporate the opportunity cost of selling on spot, pocketing the cash and buying t-bills to get a risk-free return. Rate hikes might “work” to cure inflation simply because they are regressive fiscal policy: basic income for people with net savings, tax hikes for people who are net borrowers (Claudia, you did a phenomenal job pointing out in a post I think last year how rich people get hosed by low rates and inflation, whereas poor people benefit from low rates and modest inflation). I’ve spoken w management teams who are shocked the Fed has raised this aggressively. How can four straight rate hikes be consistent with “stable prices?!”

Please acknowledge inflation shock was the sanctions. Not the Putin did it lame refrain. Russia had a legimate security concern from US arming, training UA since Victoria Nuland's coup 2014. US intent has been to destabilize Russia using Ukraine.