Why can't we shake the gloom? It's more than inflation or higher prices.

What should be good news for people seems to be falling flat even relative to prior times with high inflation.

Today’s post expands on my Bloomberg opinion piece about the unusually large degree of pessimism about the economy.1 After exploring several possibilities like inflation, partisanship, and negative news bias, I argue it’s Covid and its aftermath. Given the feedback to my piece, I will come back to my arguments about why inflation can’t explain all the gloom and explain them more thoroughly.

Setting the stage: a heated argument has been swirling among prominent economists (sharing macro charts) and regular people (sharing their daily lives) about how gloomy people should be about the economy, particularly inflation.

Here is an example from Justin Wolfers:

I am sympathetic to both sides. And being the way I am, I want to know why there is such a disagreement. So, I dug into consumer sentiment from the University of Michigan, a monthly survey of households.2

Sentiment is out of whack; what’s that telling us?

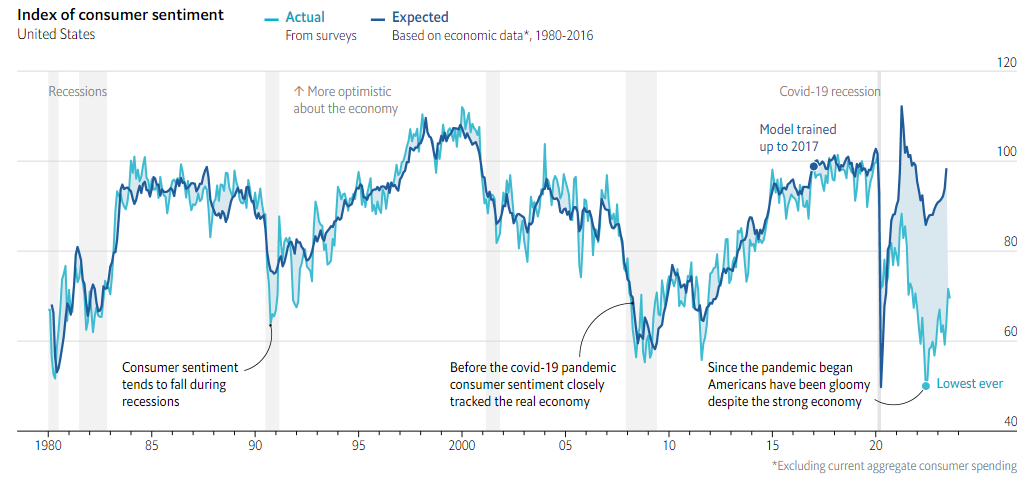

Consumer sentiment lines up with the tension between economists and regular people about the economy. See this chart on sentiment from The Economist.

The top blue line predicts consumer sentiment based on the historical relationship between sentiment and economic conditions, including inflation. The bottom teal line is the actual sentiment from the survey. The light blue area between the two is the difference between expected and actual sentiment. It’s huge and persistent relative to the past. That shaded area is what I am trying to explain. If inflation is why people are extra gloomy, why is that more than in the past? People hated the even higher inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s. Also, note that actual and predicted sentiment have improved as inflation decreased, but we are not making up the ground lost early in the pandemic.

I did the same exercise, adding other variables, like past inflation (to capture the price level). I also used the quarterly data back to the early 1960s, which includes more high inflation periods than the monthly model back to 1978. They all showed a sizeable gap in recent years.

Let’s back up and explain what this measure of sentiment is. It is constructed from the following five questions, which cover the current and future questions on personal finances and overall economic conditions:

The sentiment index combines the responses of the adults in the survey who have been chosen to be representative of all adults in the United States. Responses to all five questions reflect more pessimism than before the pandemic, especially ones about the change in personal finances during the past year and the current buying conditions for durables. Overall, sentiment is far more pessimistic than economic conditions would predict.

Usually, sentiment is closely associated with growth in consumer spending, and it can be even more valuable in predicting recessions, particularly in their early stages. But that’s not the case now. Sentiment is not following its historical patterns, and its correlation with consumer spending is much lower.3

There is no sign of an inflation mentality.

Knowing that inflation has always been a predictor of gloom, the question is, could the negative effects of inflation be worse now than before? It’s plausible. We moved from decades of low inflation to high inflation within a year. Inflation almost hit 10% last year, and many people have no prior experience with inflation above 2%

One way to get a persistent, level downshift in sentiment would be for people to switch their outlook from a low-inflation world to a high-inflation one. People hate inflation, so such a switch would usher in persistently more pessimism.

But that’s not what we find. When asked directly about inflation during the next year, people’s expectations have come down markedly as inflation has.4 Their longer-term inflation expectations have been relatively stable and are now close to pre-pandemic levels. This pattern is not what we would expect in a regime switch or an inflation mentality setting in. Even through the worst of last year, the typical person expected inflation to return to normal in the coming years. (Team Transitory.)

It may be harder to add it all up, but that’s not enough.

It’s common when economists use macroeconomic data to make a case of progress for people to cite problems like struggling with high prices of food, gasoline, or rent, as well as not having enough income to pay the higher prices. And that’s valid. Our statistics, like CPI, average hourly earnings, and consumer spending are aggregates. There are many reasons why they may not reflect people’s lives. The cost of living for lower-income households, on average, has risen the most since the pandemic began, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.5

Note, however, that the difference is modest, especially compared to the overall increase, so even if spending in high-income households looms larger in CPI calculation, it’s not understating inflation across all families by much.

High-income households experiencing lower inflation was the norm before the pandemic, too, so while it might help with the arguments about inflation, it won’t explain the extra gloom now.

In closing.

If it's not inflation, where is the extra gloom coming from? The pandemic and its aftermath fit the timing and the severity—to say nothing of the total lack of precedent—that could explain why sentiment is lower than expected. I explain in my piece.

Richard Curtin, the former director of the Surveys of Consumers at the University of Michigan, explained in his book, Consumer Expectations, how people likely form their answers. He argues that “economic expectations are an inherently social phenomenon,” so they reflect collective experiences, even non-economic ones at times. Covid-19 profoundly affected our individual lives and society overall, so it’s natural to see it clearly reflected in sentiment.

It doesn’t require everyone to still talk about or even think about Covid-19, though some do. The pandemic and our responses to it touched all our lives somehow. Concerns about high prices almost always refer back to pre-pandemic. It is a salient touch point, and one that has stuck around. Supply chains aren’t fully back to normal. Why would you expect people’s views on the economy to be? It is important to understand what ushered in the extra gloom.

If you want to play the blame game, blame Covid.

A reprint is at the Washington Post, too, and an overview of my Twitter thread).

The measure of consumer sentiment here is from the Surveys of Consumers at the University of Michigan. It is a monthly, nationally representative survey of about 600 adults. The survey began in 1946. The headline index uses five questions: change in family finances in the past year and expected during the next year; buying conditions for durables; changes in business conditions during the next year and next five years. Consumer confidence from the Conference Board and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York use different questions, and the predicted versus actual pattern may not apply to them.

It would be a mistake to ignore sentiment because consumer spending is strong in the current data. Later this month, the Bureau of Economic Analysis will revise official statistics such as GDP and consumer spending, and we may learn that expenditures were less strong than the initial estimates and move closer to the dour sentiment. I would not be surprised, though not closing the gap. One puzzle may help resolve another.

The inflation expectation questions are, “During the next 12 months [5 to 10 years], do you think that prices, in general, will go up, or go down, or stay where they are now?" and "By about what percent do you expect prices to go up, on the average, during the next 12 months [5 to 10 years]?"

Kudos to Anya Stockburger, Josh Klick, and team for their work on inflation by income data. BLS will be publishing updates regularly. See the methodology here. Creating statistics like these is painstaking work, and a statistical agency like BLS puts very high standards before any data release.

A combination of all these things. Covid came after a decade of low interest rates, relatively easy credit and low prices, steady stock market increases (the halo effect of which probably reached non-investors) and ample supply of everything. And then suddenly with Covid that changed -- not only lingering effect of that shock, but an idealization of the "before-times," plus everyone had extra cash. Expectations that everything would be great once Covid ended were not only not realized but all these new complicated problems emerged. The sudden severe interest rate increases were a shock -- a sense that the "good times are over." Prices, especially food prices, starting rising during Covid. May have been blamed on supply chain but in many cases Covid gave companies that had not had pricing power for years an opportunity to take price -- major price increases that just continued. Add in the end of student debt relief, medicaid expansion, etc etc. Just feels to many that the good times, the easy times, are over. Tend to think the strikes are a symptom, not a cause, from the folks who didn't really benefit from the "good times." Were the "good times" really any more than a big asset bubble driven by easy money for too long?

Great post. My take is that people anchor what a price was and even if it hasn’t changed in past 9 months they are still thinking what is was 2 - 3 years ago. Also with rates up if you borrow you are paying more even if the price is the same.