The Fed will not pivot

The Fed will hike another 25 basis points this week, and Powell will signal that's likely the last rate hike, and the Fed will not cut rates this year. Believe him.

Markets and the Fed both expect a hike this week and then a pause in June. They disagree on what happens after that. Markets expect the Fed to cut rates multiple times this year—referred to as a pivot—while the Fed says emphatically that it will hold rates high and not cut this year. I believe the Fed. You should too.

Here are three reasons why:

No one wants to be Arthur Burns.

Current Fed officials experienced the 1970s and early 1980s firsthand.

Inflation is persistent and won’t slow fast enough to declare victory this year.

These reasons might strike some as simplistic and out of step with the data-driven Fed. Of course, the data are still at work but don’t underestimate the pull of history and psychology in central banking.

No one wants to be Arthur Burns.

Know the history. Arthur Burns, who served as Fed Chair from 1970 to 1978, is widely regarded in mainstream circles as the worst Chair in living memory.1 Powell does not want that same legacy, and the obvious way to avoid it is to avoid Burn’s mistakes.

Ben Bernanke, a former Fed Chair and respected scholar of monetary policy, lays out the ‘sins’ of Burns in his book, 21st Century Monetary Policy. Here is a key passage on the disastrous effects of the pivots from Burns:

In an effort to contain the rise in inflation, the Fed did begin a sequence of rate increases in 1973, but these were largely reversed when the economy fell into recession. This stop-and-go pattern—tightening policy when inflation surged but then easing as soon as unemployment began to rise—proved ineffectual and allowed inflation and inflation expectations to ratchet up.

Anyone, including myself, who 'grew up' as a student of New Keynesian money/macro knows this story. We are taught that monetary policy can do good in the world, but not if you do it as Burns did. Again, to avoid Burn's legacy, one must avoid his apparent mistakes, including pivoting when unemployment rises.

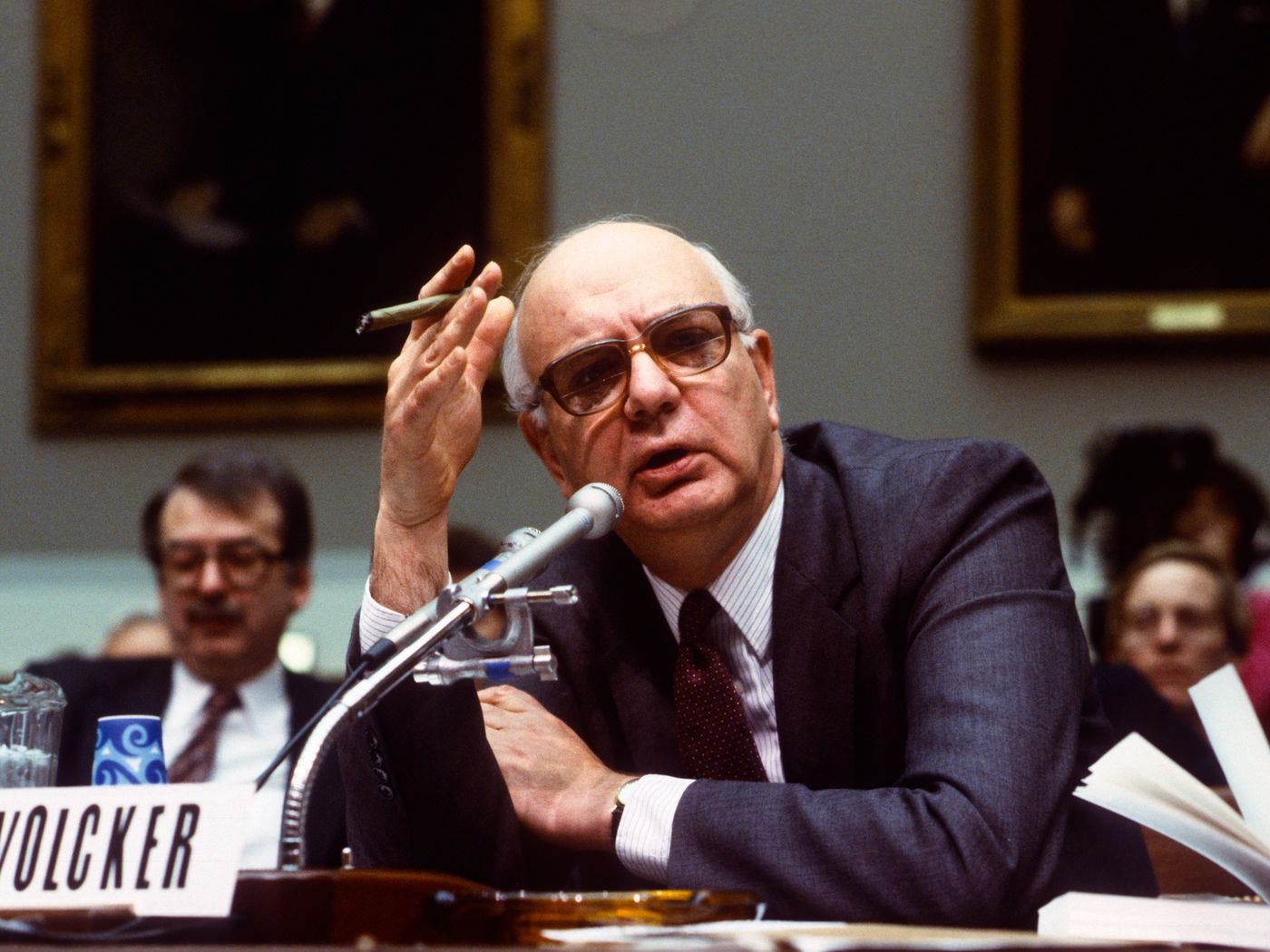

So, who does everyone want to be? Paul Volcker.

Rightly or wrongly, Volcker, who was Fed Chair from 1979 to 1987, is put on a pedestal at the Federal Reserve.2 He is viewed as one who saved us from the high inflation of the 1970s and the mistakes of Burns. And as Bernanke recounts, here is Volcker on the danger of a pivot:

In the past, at critical junctures for economic stabilization policy, we have usually been more preoccupied with the possibility of near-term weakness in economic activity or other objectives than with the implication of our actions for future inflation. …

Fiscal and monetary policies alike too often have been prematurely or excessively simulative, or insufficiently stimulative… Success will require that policy consistently and persistently oriented to that end. Vacillation and procrastination, out of fears of recession or otherwise, would run grave risks.

At the Fed, Volcker’s words are gospel. That’s the clearest warning against a pivot I could imagine. Volcker intentionally caused a severe recession to break the inflation mentality, and he did not waver until inflation came down. There are some important differences between then and now, but the aversion to a pivot is as strong today.

Furthermore, Volcker apparently had a profound impact on Powell. Powell has spoken highly of Volcker and his approach to monetary policy on several occasions. Here are a few examples from Jeanna Smialek at The New York Times:

To Jerome H. Powell, the chair of the Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker is more than a predecessor. He is one of his professional heroes.

“I knew Paul Volcker,” Mr. Powell said during congressional testimony this month [March 2022]. “I think he was one of the great public servants of the era — the greatest economic public servant of the era.”

Mr. Powell was asked this month if the Fed was prepared to do whatever it took to control inflation — even if it meant harming growth, as Mr. Volcker did.

“I hope that history will record that the answer to your question is yes,” the Fed chair replied.

Straight out of the playbook. The Fed will not pivot this year, recession or not. History looms large at the Fed and Volcker above all else.

Current Fed officials experienced the economic crisis in the 1970s and early 1980s firsthand.

Life experiences matter. It’s true for the decisions we make in our daily lives, and it’s true for the policy decisions central bankers make. Research by Ulrike Malmendier, Stefan Nagel, and Zhen Yan shows how personal experience with inflation affects central bankers’ views on the inflation-unemployment tradeoff in monetary policy:

Personal experiences of inflation strongly influence the hawkish or dovish leanings of central bankers. For all members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) since 1951, we estimate an adaptive learning rule based on their lifetime inflation data. The resulting experience-based forecasts have significant predictive power for members’ FOMC voting decisions, the hawkishness of the tone of their speeches, as well as the heterogeneity in their semi-annual inflation projections. Averaging over all FOMC members present at a meeting, inflation experiences also help to explain the federal funds target rate, over and above conventional Taylor rule components.

So, how much personal experience does the current FOMC have with high inflation before today? A considerable amount. Many were young adults during the Great Inflation of the 1970s and its aftermath in the early 1980s. Specifically, in 1982 when unemployment peaked over 10%—during the recession that Volcker engineered to bring down inflation—Chair Powell was 29 years old, the oldest among the current FOMC, New York Fed President John Williams was 20, and the other voting members ranged from ages 9 to 24.3

According to the research, that lived experience would at least to some extent increase the emphasis they place on inflation when there appears to be a tradeoff between it and unemployment. That same exposure is true for many of the older macroeconomists advising on policy. The inflation of the late 1970s and the crushing recession of the early 1980s are life, not abstract history, for them.

Regardless of whether they can remember it personally, nearly all the Fed officials and New Keynesian macroeconomists see the inflation in the 1970s as the closest comparison to today. And that’s even though back then, we did not shut the economy down due to a global pandemic, nor was there a war in Europe, nor were inflation expectations anchored. Nevertheless, that is where the minds of our central bankers and older talking heads are. And that means Arthur Burns and Paul Volcker have made a comeback.

We should not push the idea of lived experience too hard. It’s one of many factors, but research does show a relationship. The dovish sentiment is almost entirely gone from the FOMC, with inflation high and unemployment low. During the past year, more dovish Fed officials before the pandemic, such as Mary Daly and Neel Kashkari, Presidents of the San Francisco and Minneapolis Fed, respectively, have shifted their emphasis almost entirely to inflation.

Inflation is persistent and won’t slow fast enough to declare victory this year.

In the decade before the pandemic, the Fed faced the opposite problem: inflation that was slightly below target despite low unemployment. The unemployment rate at the end of 2019 was the same as now, despite inflation being notably lower then. The Phillips Curve at that time appeared flat; unemployment could rise or fall, and the inflation rate stayed constant. That made it difficult to rely on the Phillips Curve to forecast inflation.

In response, the Board staff turned to a suite of statistical models to explain the lowflation dynamics after the Great Recession. (See the 2017 memo to the FOMC.) These are more in the spirit of ‘let the data speak,’ as opposed to forcing the data into a structural model:

The staff’s underlying inflation assumption is informed by considering the long-term trend rate of inflation that is implied by a range of univariate and multivariate time-series models, together with the long-run level of inflation implied by Phillips curve models that condition on measures of expected inflation from surveys or financial markets …

Although the time-series models do not provide a structural characterization of trend inflation, the fact that both survey measures of longer-term expected inflation and the trend estimates from several time-series models have been relatively stable since the late 1990s provides some (admittedly circumstantial) evidence that the two phenomena are related, with inflation’s long-term trend ultimately determined by longer-term expectations.

The trend in this framework is crucial, and as with any trend, it will move slowly. But after more than two years of elevated inflation, that trend has drifted up. (See Riccardo Trezzi’s excellent analysis.) And with the historically high degree of persistence, these models will be slow to predict a decline in inflation. And, for yet another reason, the Fed will be slow to declare victory.

The problem with statistical models is that they project past relationships forward. Numerous historical relationships have broken in this cycle. And in these models, we don’t know why the dynamics are persistent. What’s the story, and to what degree would it apply now? The story matters, and it must almost certainly be a complex one.

Setting aside my concerns about statistical modeling, the Fed’s model is backward-looking and will take longer to signal ‘all clear.’ Tomorrow is May. There is insufficient time to get a string of PCE core inflation reads sufficiently low this year, even if we go into recession. The Fed will not cut until it’s clear it has beaten inflation. That won’t be apparent this year, so there will be no pivot.

In closing.

On Wednesday at the Fed’s press conference, Chair Powell will once again tell us that the Fed will not cut this year, and once again, the markets will ignore him and expect cuts. Here history and psychology are on the Fed’s side, and they are the ones who will cast the votes. I do not expect the Fed to blink in a recession. And I do not expect them to blink in financial market turmoil. And that worries me.

Addendum: Most frequent pushback on my post has been my statement, "Powell will signal that's [in May] likely the last rate hike." My reasons: 1) Fed does not like to surprise markets; it must signal something about June. 2) Failure of Silicon Valley and friends is doing some of the Fed’s work by tightening lending conditions. 3) "Likely" only means 50%+ chance, not 100%,

Chris Hughes, a founder of Facebook and now a doctoral student at Wharton, recently wrote an essay, “Rethinking Arthur Burns, the “Worst” Fed Chair in History.” It’s an interesting read and does not expect anyone at the Fed or the New Keynesian consensus to agree. And so, all the better, he wrote it.

Volcker was the President of the New York Fed and Vice Chair of the FOMC from 1975 to 1979, making him the second most powerful member of the FOMC under Burns. But he essentially gets a pass from Bernanke, “Volcker sat at the chair’s elbow and watched in frustration as inflation worsened. He argued for tighter policy but was constrained by the tradition that the vice chair votes with the chair….” There’s a lot to unpack there, but the most disconcerting is the culture of forced consensus that does not allow divergent views. That’s a culture that continues today.

The ages are from Wikipedia and may not be completely accurate. There was no birth year on Philip Jefferson’s Wikipedia page.

Another wonderful read, but as I've said many times before, Volcker is no hero especially to the middle class for his damaging recession in the 80's in his war on inflation. As Warren mosler has said, rate hikes are regressive stimulus to bondholders its a terrible way to fight inflation.

We could use better fiscal policy out of DC but we all know that isn't happening. But ultimately I agree, it will be another 25 point hike then afterwards, a pause.

Thanks Claudia. You’re of course correct. Basically, history dictates the Fed lacks proper authority and tools to mitigate inflation without hurting Americans. Many macroeconomists I follow Stephanie Kelton, Warren Moselor, Dirk Ehnts, and the like point to the OPEC oil embargo as the “main” cause for the “70s” inflation and Volker as ineffective as his actions caused double dip recession and the main historical incident to get us out occurred due to the Iran /Iraq War reversal impacts on oil production. We hoped for a pause for the past two months. June works and I agree time should produce more strong economy indicators but not move a conservative Fed to cut rates. Now if we could get the marketeers to resist price gauging and pass it off as inflation. Sadly, “the market” consists of fearful people who subscribe to hyper capitalism and individualism as history shows.

I remain optimistic. MMT has proved successful throughout the pandemic despite the nihilism of the right. The economy needs Fiscal policy to resource effectively and assess to tweak implementation. The Fed should work to do no harm.