The Fed is firmly in the 'whatever it takes' mode of its long-standing risk management plan

Expect Chair Powell's first Jackson Hole speech of his second term to reinforce the message in the one in his first term: risks to stable inflation expectations are an emergency at the Fed.

Today’s post was for paid subscribers only. Now it is open to everyone.

Credibility is “the quality of being trusted and believed in.” It’s doing what you say you will do and then delivering. Credibility is essential to the Fed, and it’s on the line.

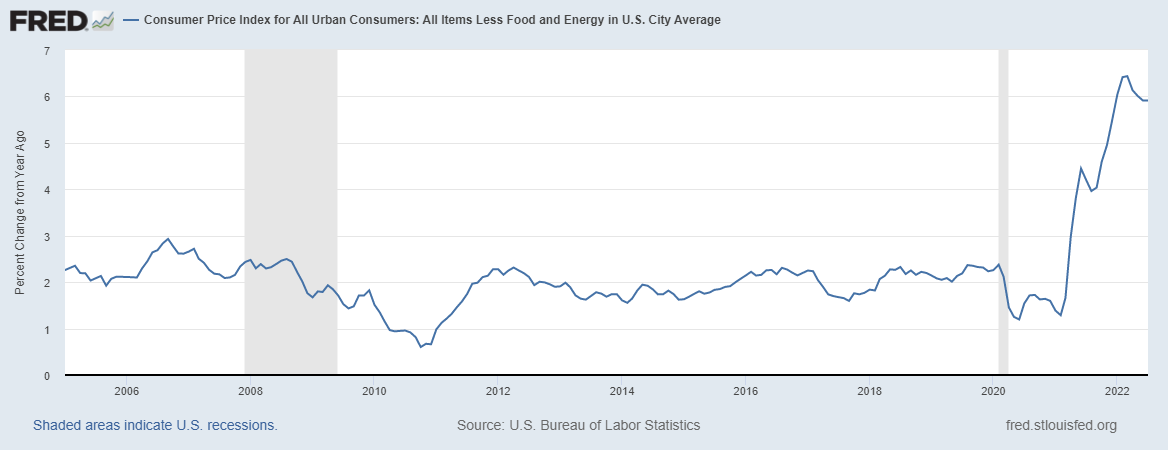

Inflation remains high and increasingly broad-based, threatening the Fed’s credibility as an inflation fighter. But, after some informed but incorrect predictions last year, it is now doing precisely what it has long said it would do in emergencies like this. A crisis is not panicking; it’s getting back to basics. Stick to the plan.

You don’t have to like it, but it should be no surprise that the Fed is being aggressive now. Now it’s time to convince everyone that it means it.

Understanding the Fed requires more than watching the data and hanging on its every word; it requires knowing the logic of its long-standing plan. I went back and read Powell’s first Jackson Hole speech, and it’s there.

The Fed’s long-standing plan

In 2018, in his first speech as Chair, “Monetary Policy in a Changing Economy,” and well before the current crisis, Powell reiterated the Fed’s long-standing risk management plan for monetary policymaking:

[When] you are uncertain about the effects of your actions, you should move conservatively.1 In other words, when unsure of the potency of a medicine, start with a somewhat smaller dose …

[but] this is not a universal truth, and … two particularly important cases [exist] in which doing too little comes with higher costs than doing too much. The first case is when attempting to avoid severely adverse events such as a financial crisis or an extended period with interest rates at the effective lower bound. “We will do whatever it takes” will likely be more effective than “We will take cautious steps toward doing whatever it takes.”

The second case is when inflation expectations threaten to become unanchored. If [inflation] expectations were to begin to drift, the reality or expectation of a weak initial response could exacerbate the problem. I am confident that the FOMC would resolutely “do whatever it takes” should inflation expectations drift materially up or down …

Translation: The Fed has two modes in times of uncertainty: cautious and aggressive. The former is standard; the latter is not. The Fed switches in only two exceptional cases: financial crises and stable inflation expectations at risk. It’s a high bar to switch and a high bar to switch back. This plan is not new.

Of course, actions speak louder than words, and during the past two and half years, the Fed has so far stuck to its word:

In the spring of 2020, the Fed went straight to aggressive with financial markets in a tailspin. The support was swift and massive and kept going until it worked. Markets stabilized quickly.

Then came a surge in inflation in 2021. The Fed's cautious approach to tightening, both in ending its asset purchases and its first increase in the federal funds rate. That aligns with uncertainties about how its actions would affect financial markets and the economy. Would it rattle markets as with the ‘taper tantrum,’ or would it overdo it as the pandemic disruptions unwound? It was cautious. Doing too much too soon got considerable weight.

One can reasonably argue (and the Fed agrees in hindsight) that the Fed remained cautious too long in its approach to inflation risks. It was slow as a committee to connect “materially” to the drift up in inflation expectations. It has now.

Since early 2022, the Fed moved decisively to the “whatever it takes” mode to bring inflation down. We hit its high bar. Persistently high inflation risks unstable inflation expectations more urgent than a recession. One can argue whether that’s overblown to some extent, but the Fed is sticking to its word. It will not blink at a recession, not with inflation high.

The big question is what’s the high bar for the Fed to be convinced that inflation expectations are no longer under threat. That’s not inflation back at 2%, but it’s also not a softish August CPI. When will it move back to being cautious and give more weight to the uncertainties around the broader effects of its policies? Powell is unlikely to go there tomorrow. It’s too much nuance for financial markets to handle.

How close is the FOMC likely to being cautious again?

Not that close. Inflation is not convincingly coming down. Last summer was the head fake that the Fed will not fall for again, nor should it. And this summer does not look all that different on the slowing. And we are twice as far from target now.

There are encouraging signs for the Fed on lower inflation in the pipeline. Its aggressive tightening since the spring is having a significant effect on interest-rate-sensitive demand. The housing market is cooling off quickly. But it’s a long and [highly] variable’ lag from home sales to overall inflation.

That’s not enough to switch back to cautious. The risks around inflation are too high; thus, the risks around inflation expectations are too high. Despite the housing data, the Fed remains in its whatever-it-takes mode; clear words from Powell tomorrow of more tightening should underscore that tomorrow.

Wrapping up

A mantra of the Fed is that it is data-driven. But that brushes over the fact that which data and to what degree depends on what mode of risk management the Fed is in. In a few exceptional cases, one of which we are in now with high inflation, the scope and importance narrows. The Fed is following the plan, as they said they would. It is keeping its word. That’s the best they can do now to defend their credibility for now.

Here Powell describes research beginning with the “Brainard principle,” that economist William Brainard in 1967, which informs the Fed’s view on monetary policymaking under uncertainty. The current version reflects decades of research and experience.

Great article. Do you think the quick recovery of TIP breakeven rates back below 3% encourage the Fed that their policies are working?