The dark side of a data-driven Fed

Data are central to Fed policymaking, and that's a good thing. However, data are imperfect and do not speak for themselves, so sometimes they lead us astray.

Today’s post is mainly for paid subscribers. First, for everyone, I discuss the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow. Behind the paywall, I talk about inflation expectations from the Michigan Survey.

A key mantra at the Fed is that its policy decisions are data-driven, as they should be. The Fed makes a serious effort to ground its analysis, forecasts, and decisions in data. Even so, data differ in quality, often send contradictory messages, and can be hard to interpret. More often than not it’s how we use the data that can get us in trouble.

GDPNow is in the spotlight now

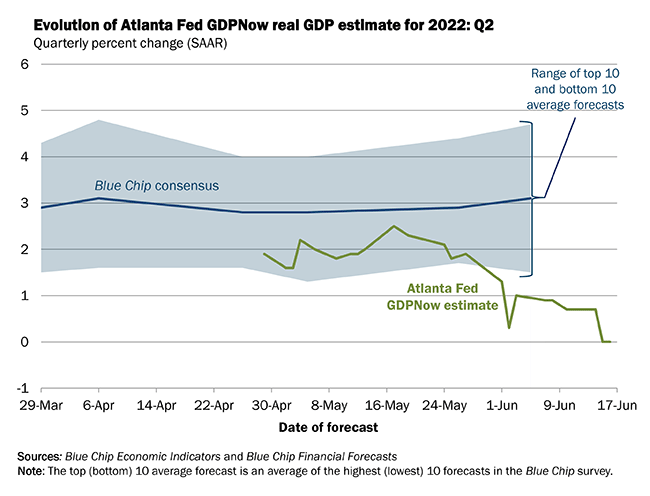

We have an enormous amount of data about the economy. And nowcasting models are an approach to summarizing them. The basic idea is to put a bunch of macroeconomic data in a statistical model and see what it pushes out. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow is one example. And it’s gotten a lot of attention recently.

Its current forecast for no GDP growth in the second quarter is gloomy. It’s much worse than professional forecasters. Plus, after a decline in GDP in the first quarter, their forecast would get us uncomfortably close to the recession rule of thumb of a two-quarters decrease in GDP.

GDPNow was in a recent Wall Street Journal piece, “Recession probabilities soar as inflation worsens:”

One closely watched model—the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow tracker—estimates that gross domestic product is on track to remain unchanged at an annual rate over the three months through June 30.

I do not worry about the Fed getting too worked up over GDPNow, though they are watching it. The recent solid growth in consumer and business fixed investment should outweigh GDPNow. That said, GDPNow is a useful exercise and could be right.

It’s mainly the (change in) the change in inventories that is driving their forecast. Inventories were one of two factors behind the decline in the first quarter GDP.

Inventories may be a big drag on GDP growth again. And GDPNow incorporates monthly data so far; however, data on inventories are hard to parse. I looked at some available data and didn’t see red flags.

My concern is that GDPNow is cherry-picked out and given media coverage because it fits the recession narrative. Dig into the forecast details on its webpage, and you might think twice about it. See their FAQs. The Fed knows how to use this one.

Below the paywall, I talk about inflation expectations from the Michigan Survey and why they should not have played a leading role in the Fed’s 75-basis-point increase this month. My discussion draws on my work with the Michigan Survey at the Fed and my research with it.

In mid-June, Jay Powell pointed to inflation expectation as one reason the Fed raised its policy rate by 75 basis points, the largest increase in nearly thirty years.

… inflation has again surprised to the upside, some indicators of inflation expectations have risen, and projections for inflation this year have been revised up notably. In response to these developments, the Committee decided that a larger increase in the target range was warranted at today’s meeting.

On the Friday before the FOMC meeting, the Michigan Survey published its preliminary estimate of inflation expectations for June. Over the next five to ten years, the median expectation for inflation increased from 3.0% to 3.3%, a frighteningly large increase for the Fed. Not to me; I was more frightened that it was part of their justification for an aggressive hike. The upside surprise in the CPI would have been a sufficient explanation. (Though 50 basis points would have been a better increase.)

The survey says … what?

We got the final Michigan Survey results for June last week; it was 3.1%, a notably smaller increase than the preliminary. That’s not a frightening read. It is within the range over recent decades. And it’s well below the 1970s and 1980s.

And I am not the only one who noticed the head fake from the Michigan Survey.

I disagree with the “only 600 respondents” criticisms. The 600 people who answer the monthly survey are ‘special’ because they are selected to be representative of the U.S. adult population. The Michigan Survey started after World War II. It’s well done. Of course, no survey is perfect, and response rates have fallen significantly over time.

However, the preliminary results for June that informed the 75 basis point hike are from about 400 respondents, who are not representative. Only the final sample is. A non-representative survey (small or large) shouldn’t play a central role in policymaking. Again, it was in line with the CPI, so I am not saying it’s wrong, and there was no way to forecast the revision. Even so, its outsized role is risky.

Know thy data: inflation expectations edition

Above all, understand the data. That’s the first step to avoiding a head fake or overreliance on a data series. Here are the questions that respondents are asked:

Then unlike other questions, some responses “three types of adjustments that are made to these response distributions: imputations for missing information, corrections for the misinterpretation of response codes, and the truncation of outliers.” See this 56-page report for more detail. Getting the median is fun too.

If you are an economist, you probably love these survey questions. The median inflation expectation (in percentage points) is exactly what you need to plug into your theoretical models. But, in reality, these are complicated questions.

While working on research with the survey, I had a chance to listen to the survey tapes. The inflation expectations were by far the most challenging sequence. The vast majority answered, but you could tell some people struggled even with the idea of a percent and others with the inflation concept. I have often thought if Fed officials and macroeconomists listened to the tapes, they might be more cautious with the data too.

Inflation expectations loom large at the Fed

Ok, you might ask yourself why are such small moves in inflation expectations such a big deal. They play a central role in models of monetary policy. As a result, their stability referred to as anchored, is considered extremely important and a direct outcome of Fed policy. I have my concerns with the standard model. See my FEDS Note on “Limited Attention and Inflation Expectations.” I have even bigger concerns about basing big policy moves on hard-to-measure concepts.

And I am not alone in my skepticism; see my earlier post on Jeremy Rudd’s, an economist at the Fed, critique of inflation expectations.

No signs of inflation mentality now

The big fear right now is that an inflation mentality could set in. If people think prices will continue to rise, they might go to their bosses and demand a raise. If they get one, the boss will pass some along to consumers with higher prices. That’s the making of a wage-price spiral. Likewise, people might buy something before prices increase. The extra demand would then put upward pressure on prices. In either case, expecting high inflation can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. It occurred in the 1970s and is the last thing the Fed wants right now. That’s why the jump in the inflation expectation caused so much consternation.

Other questions in the Michigan Survey that I’ve been following are less worrying:

About the big things people buy for their homes -- such as furniture, a refrigerator, stove, television, and things like that. Generally speaking, do you think now is a good time or a bad time for people to buy major household items?

Why do you say so?

People are clear that now is not, and higher prices are the most cited reason.

And encouragingly, few consumers think it’s a good time to buy in advance or borrow in advance, a contrast from the 1970s. We do not have an inflation mentality.

Of course, things could worsen. That’s a risk as long as inflation stays elevated. But now is not the time to sound the alarm bells.

Wrapping up

A data-driven Fed is a good Fed. The lesson of my post is not to ditch the Michigan Survey. It is a valuable pulse on consumers. The lesson is not to ignore its preliminary results. It is helpful to get an early read. The lesson is to be very careful, especially when doing something big. Using data well is hard, and it pays off.

Thank you for financially supporting my Substack. Please send me feedback or suggestions for topics to cover. And of course, it would be great if you recommended my work to others.

Excellent post, especially the deep background in the 56-page procedure report. As a matter of curiosity, have they tested their 25/75 dispersion measure with subsequent data since 1996? Thanks for your work!

Great article and drill down into the Michigan Sentiment and its revision. Small number of respondents having a potential big sway on public policy. Thanks for the insights.