"Softening in labor market conditions" will hit millions of workers and their families hard

The Fed raised rates another 75 basis points this week in its aggressive effort to curb inflation. Worryingly, it sees the strength of workers as standing in the way of its goal.

The press conference was tough, and they will get much harder very soon.

In only four months, the Fed has raised its interest rate by 2 1/4 percentage points, including two back-to-back 75 basis point moves. The cost of borrowing for consumers, like mortgage rates, has jumped even more. The Fed will keep going.

The Fed’s ‘whatever it takes’ attitude toward fighting inflation generally has had support. That won’t be the case at its September meeting. The slowing in economic activity is evident and spreading. The next shoe to drop is the labor market. That’s the one that matters most to regular people. That’s the one that hurts more than inflation. And it’s the cost of fighting inflation that’s the hardest for the Fed to justify.

Why is the labor market a problem?

Good for workers is bad for the Fed.

Despite these developments [recent indicators of spending and production have softened], the labor market has remained extremely tight, with the unemployment rate near a 50-year low, job vacancies near historical highs, and wage growth elevated. Over the past three months, employment rose by an average of 375,000 jobs per month, down from the average pace seen earlier in the year but still robust. Improvements in labor market conditions have been widespread, including for workers at the lower end of the wage distribution as well as for African Americans and Hispanics. Labor demand is very strong, while labor supply remains subdued with the labor force participation rate little changed since January. Overall, the continued strength of the labor market suggests that underlying aggregate demand remains solid.

Note, “tight” is bad, as is “demand” now.

Fedspeak translation: Low unemployment and high wage growth, especially among marginalized workers, many jobs to apply to, workers being able to move to better jobs, more full-time work, people enjoying retirement, etc. are key contributors to businesses raising prices more rapidly (high inflation) than in the past.

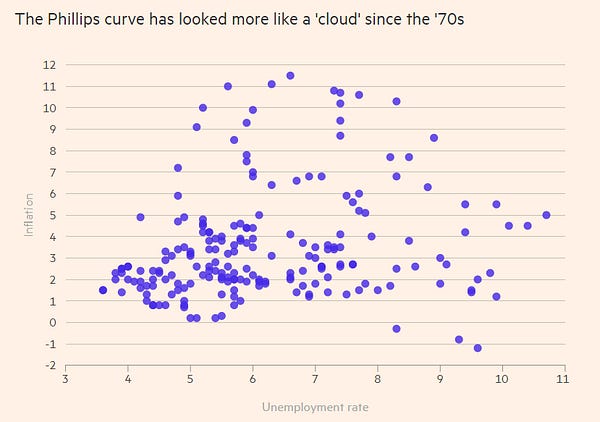

Evidence? That’s the Phillips Curve, which suggests a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment, talking. And it’s not up to the task now.

Fedspeak isn’t up to the task either. More clarity is necessary: Why do we need softening in labor markets? What does that even mean? Why isn’t slowing growth in spending and investment enough? What about fiscal unwinding or pent-up Covid demand and geographic mobility easing? How much of the current inflation is due to low unemployment? What are the mechanisms? Why use wages and not personal income when thinking about inflation during the past year and a half? What institutions or norms today would cause a wage-price spiral? What are the other reasons businesses are raising prices?

No, inflation is not “the bedrock of the economy”

But it got worse at the presser. Twice Powell dodged Steve Leisman’s question about how a recession would affect the Fed’s actions, pivoting instead to inflation:

STEVE LIESMAN. Steve Liesman, CNBC. Thanks for taking my question, Mr. Chairman. Earlier this week, the president said we are not going to be in a recession. So I have two questions off of that. Do you share the President's confidence in not being in a recession, and second, how would or would not a recession change policy? Is it a bright line, sir, where contraction of the economy would be a turning point in policy? Was there some amount of contraction of the economy the Committee would be willing to abide in its effort to reduce inflation?

CHAIR POWELL. So, as I mentioned, we think it's necessary to have growth slowdown. And growth is going to be slowing down this year for a couple of reasons. One of which is that you're coming off of the very high growth of the reopening year of 2021. You're also seeing tighter monetary policy. And you should see some slowing. We actually think we need a period of growth below potential, in order to create some slack so that the supply side can catch up. We also think that there will be, in all likelihood, some softening in labor market conditions. And those are things that we expect, and we think that they're probably necessary if we were to have-- to get inflation. If we were to be able to get inflation back down on the path to 2 percent and ultimately get there

STEVE LIESMAN. The question was whether you see a recession coming and how you might or might not change policy.

CHAIR POWELL. So, we're going to be-- again, we're going to be focused on getting inflation back down. And we-- as I've said on other occasions, price stability is really the bedrock of the economy. And nothing works in the economy without price stability. We can't have a strong labor market without price stability for an extended period of time. We all want to get back to the kind of labor market we had before the pandemic where differences between racial and gender differences and that kind of thing were at historic minimums, where participation was high, where inflation was low. We want to get back to that. But that's not happening. That's not going to happen without restoring price stability. So, that's something we see as something that we simply must do. And we think that we don't see it as a trade off with the employment mandate. We see it as a way to facilitate the sustained achievement of the employment mandate in the longer term.

Price stability, which the Fed defines as 2% inflation, is important. But 2% inflation is not the “bedrock of the economy.” Workers and businesses; make real contributions, not price tags. Durable good prices fell for decades until Covid blew up fragile supply chains. Why did they fall? Because workers and businesses made higher and higher quality goods. That’s the better way to fight inflation! An even better one this week:

The Fed can’t wait for that supply and innovation to come online, but it can avoid overselling the importance of low inflation. And, again, it must be clearer. Powell repeatedly said the Fed needs “compelling” evidence of inflation moving toward 2% to stop. And that’s it. If a recession happens, and it doesn’t break core inflation, then they will keep hiking. Core PCE inflation last quarter was 4.4% at an annual rate, down from its high near 6% last year. How compelling is compelling?

Finally, his “we all want to get back to the kind of labor market we had before the pandemic” is bizarre. Inequities in the labor market are as narrow as ever now. Prime-age workers are back. I bet most retirees are okay with being retired. Now, I believe that Amazon and Starbucks execs dealing with union drives and every businesses that can’t find cheap labor would like to return to the pre-Covid labor market. The Fed would certainly like to go back. But, we all are not that “we.”

A recession is worse if you live paycheck to paycheck

The very last question of the press conference broke me.

MARK HAMRICK. I can remember when you held your first news conference and you vowed to be a very plainspoken chairman and we're thinking today about the impacts of Fed policy on individuals as well. What would you say to individuals or households who may yet lose their jobs in this tightening cycle in the fight against inflation as they try to translate what Fed policy means to them in this complicated economic landscape?

CHAIR POWELL. So, I guess the first thing I would say to every household is that we know that inflation is too high. We understand how painful it is. Particularly for people who are living paycheck to paycheck and spend most of that paycheck on necessities, such as food and gas. And heating their homes. And clothing and things like that. We do understand that those people suffer the most. Middle class and better off people have some resources where they can absorb these things. But many people don't have those resources. So, it is our job, it is our institutional role, we are assigned uniquely and unconditionally the obligation of providing price stability to the American people. And we're going to use our tools to do that. As I mentioned, there will be some, in all likelihood, some softening in labor market conditions …

Yes, people living paycheck to paycheck are hurt the most by high inflation.

Even so, almost by definition, they are the ones who will be slammed by losing their paycheck. They will suffer the most from the Fed's being “unconditionally” focused on inflation. They are the ones who will suffer from the aggressive tightening, recession or not. (Note, the Fed has two obligations, not one as he says.) And the “softening in the labor market” that’s workers losing their jobs, hours, and raises. The ones at the bottom go first. Here’s research by Ariel Gelrud Shiro and Kristin F. Butcher at the Brookings Institution:

Focusing on displacements [job loss] that occurred between 1989 and 2019, we find that Black workers are 67 percent more likely to be displaced than their white peers, on average. Workers without a bachelor’s degree are also 67 percent more likely to be displaced than those with a bachelor’s degree, and workers whose parents are in the bottom half of the income distribution are 27 percent more likely to be displaced than those with parents in the top half.

No one on the FOMC will get laid off. They want “softening,” but they will not be the “softening.” Please stop citing the hardship inflation inflicts on low-wage workers without mentioning the disaster unemployment is for them. And in the spirit of equity, tell us how many dollars in purchasing power the 1% lose on their savings with the higher inflation now. Then let’s talk about who’s benefiting from 75 bps.

Wrapping

In a better world, the Fed would not have to go it alone on inflation. In a much better world, Covid and Putin would not exist. But we don’t live in those worlds. The Fed should be tightening, but not as fast. Powell should not have signaled rate increases for the rest of this year, given how much activity is slowing. Above all, the Fed must better explain what they are thinking and doing. The American people deserve straight talk and ‘forward guidance’ more than markets do. The stakes are high.

Another benefit of cutting the Fedspeak is the wake-up call to Congress, which has some tools to fight inflation and, most importantly, to ensure we don't break inflation on the backs of those with the least. Telling the Fed to stop hiking is largely a waste of time. Instead, help fight inflation and design fiscal policy for the coming recession. Workers did not cause inflation, and they should not pay for bringing it down.

Note: My post this weekend will unpack Powell’s comments on forward guidance at the press conference. That was the news from this FOMC meeting and says a lot about the fate of that tool. I promise, for Fed watchers, it’ll be worth a paid subscription.

As always, a pleasure to read, though I still have some curiosities about the effects of a windfall tax, as it has been the case in Spain or the UK? Does it have any impact on the inflation rate at all or does it actually lead to a rise in costs, because companies, witnessing the adaptation of such a tax, will then adjust their prices?

By focusing on top-line inflation, the Fed targets a lagging indicator using a tool with long and variable delays. How can they avoid getting whipsawed? And how does embedding higher corporate taxes into the price structure help inflation come down, unless those taxes reduce aggregate demand (through layoffs)?