Macro tip #1: Learn from your mistakes

Economists are often asked to predict the future, but no one can. The present is even hard to explain. Good macro isn't the numbers; it's the story. Getting that right takes trial and error.

In grad school, I learned macroeconomic theory, cutting-edge research, and statistical tools. At the Board, I learned how to apply them (or not) to the real world, so I could give the best advice possible to policymakers. In a series of posts, I will share some good practices for thinking about the economy. They’re tips everyone can apply.

Learn from your mistakes

Macroeconomists—even those who aren’t professional forecasters—make predictions all the time. Something happens in the world like a crash in house prices or a global pandemic. Then we use our tools to say what might happen next. Likewise, when Congress and the Fed contemplate new policies, we’re on the scene, telling them what the effects might be on the economy. What’s out track record? Not so good.

Scene: in 2008, me as a newbie in my section chief’s office at the Board.

Me: Do we get fired for making bad forecasts?

Him: No, but you get in trouble for covering them up.

Some might see that as a ‘get-out-of-jail-for-free card.’ It’s not. I worked at the Fed for a decade on the staff’s macro forecast. Starting in 2008, I made countless forecasts. Some were spot on. Some were wildly wrong. Regardless of whether the topline numbers in the data release matched my forecast, I poured over over every detail in the data. (The inflation team even more so.)

Why? Getting the numbers right is not the important part. It’s getting the story right. Policymakers need to understand the whys and the what’s next. Stories have a beginning, middle, and end. When the data roll, we are, at best, in the middle, and it’s the end or at least the next chapter that we need to tell. We need to explain the other possible paths too.

It’s impossible to get the story right on the first try. Even if you’re right, the world might change. Repeatedly, Covid-19 and people’s responses to it have surprised us all. Those surprises have implications for the economy, so macroeconomists have had to do a lot of re-writes. The first step is admitting when your story was wrong. Own it, and then fix your story. Try, try, again.

One of my BIG misses this year was on payroll employment in April 2021:

Step 1: Write it down.

Tell a story, give a number—before the data come out. Here was mine:

Step 2: Look the data straight in the face.

Admit when you were wrong. Data speak, you listen.

Do not brag if you are right. Why? It could have been luck, it might be revised away, and everyone already knows (see Step 1). No victory laps.

Step 3: Figure out how you went wrong.

Update your story and numbers.

I go to a meeting of labor market experts after every jobs report. It was dismal that month. While I was wildly too optimistic, basically all forecasters whiffed a lot.

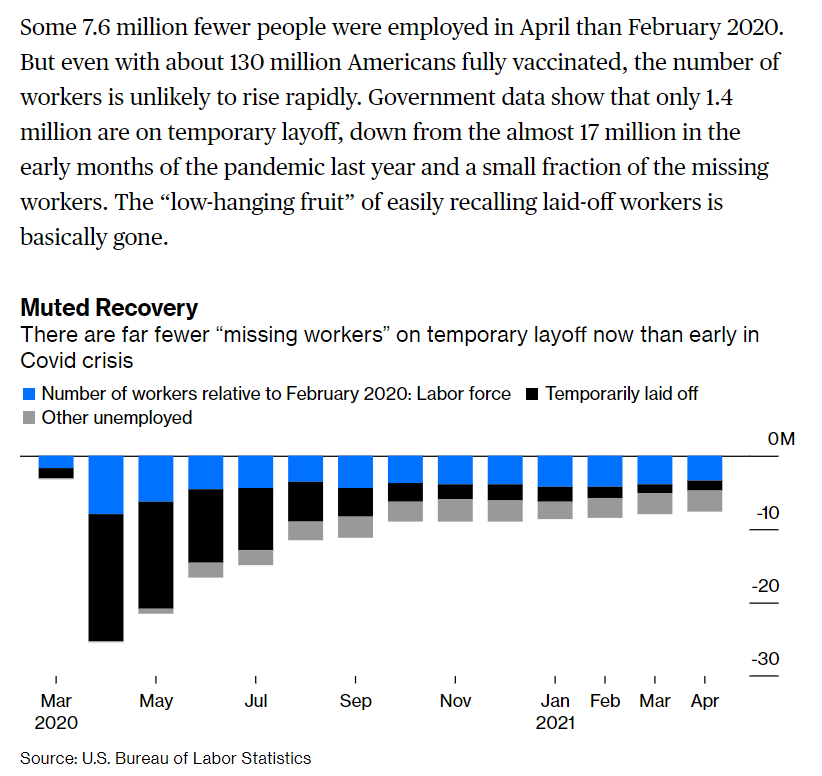

No time for a pity party. At that month’s meeting Jed Kolko talked about how many fewer people remained on temporary layoff in 2021 relative to the start of the recession. I dug into the data more and wow, that’s what I had missed.

Then I wrote a Bloomberg article on it. Share what you learn with the world!

In that piece, I also applied what I had learned to my advice to policy makers:

I also offered evidence-based solutions that would work. (Read my piece.)

That’s how good macro is done. Rinse and repeat. Do your very best.

Finally, above all else, be humble.

Here’s Dave Stockton in 2009, Division Director of Research and Statistics:

Mr. Chairman, In looking at the myriad ways in which we were surprised by the incoming data and forced by evolving economic and financial circumstances to revise our forecast, I began to think that maybe my wife was on to something when she recently gave me a T-shirt that reads “Mind of an Athlete–Body of a Genius.” Well, as you know from reading the Greenbook [report with the Board staff forecast], we did mark down substantially our forecast this round.

Dave Stockton is one of the best macroeconomists I have ever met. During the worst of the crisis, he told staff, “Put your head down and do your work. The FOMC needs your best work.” He also told some jokes as above, because as he put it, “If you are not laughing you are crying.” It’s hard to forecast when you’re crying. I know.

I learned from the very best. Happy to share their macro wisdom with you.

Please consider a paid subscription. Your financial support will help me continue to write here regularly for the public. This week I will start my paid-subscriber only posts too. First, one will be on the new inflation and consumer spending data coming out Friday.

It seems the most important thing about learning is distinguishing mistakes in exogenous (especially policy, especially Fed policy) variables from mis-specification of the model.