Tomorrow is the jobs report for August 2024. There is intense attention for any clues on the direction of the U.S. labor market, particularly with the Fed set to begin cutting rates in a few weeks and concerns about a possible recession swirling. We will rightly spend a lot of time assessing labor market conditions in the next several months, so today’s post shares some key indicators to watch.

Keep in mind that no data point or data release will be decisive. They are more likely to confuse than clarify in isolation. Plus, there are near-infinite data configurations that should cause concern or encouragement. The interpretation of the data, especially as it affects Fed rate cuts, will be contested, and history is unlikely to be as good of a guide as in the past. All that said, the stakes are high to try to get it right.

Fed Chair Powell made news last month in Jackson Hole when he declared “the time has come” for the Fed to cut rates. After a laser-like focus on lowering inflation for almost three years, protecting the labor market against further weakening is also the Fed’s objective:

Overall, the economy continues to grow at a solid pace. But the inflation and labor market data show an evolving situation. The upside risks to inflation have diminished. And the downside risks to employment have increased. As we highlighted in our last FOMC statement, we are attentive to the risks to both sides of our dual mandate.

The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear, and the timing and pace of rate cuts will depend on incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks.

We will do everything we can to support a strong labor market as we make further progress toward price stability. With an appropriate dialing back of policy restraint, there is good reason to think that the economy will get back to 2 percent inflation while maintaining a strong labor market. The current level of our policy rate gives us ample room to respond to any risks we may face, including the risk of unwelcome further weakening in labor market conditions.

It’s a remarkable and appropriate commitment to the Fed’s dual mandate—stable prices and maximum employment, especially when year-over-year PCE inflation remained above target at 2.5% in July and the unemployment rate at 4.3% was only a touch above the median of Fed officials’ longer-run projections. Recalibrating policy to avert further slowing in the labor market while maintaining progress on inflation is difficult. Even the first step of assessing labor market conditions is hard.

Powell’s case for labor market conditions.

The key passage from Powell’s speech offers a good starting point for a data dashboard on labor market conditions:

Today, the labor market has cooled considerably from its formerly overheated state. The unemployment rate began to rise over a year ago and is now at 4.3 percent—still low by historical standards, but almost a full percentage point above its level in early 2023 (figure 2). Most of that increase has come over the past six months. So far, rising unemployment has not been the result of elevated layoffs, as is typically the case in an economic downturn. Rather, the increase mainly reflects a substantial increase in the supply of workers and a slowdown from the previously frantic pace of hiring. Even so, the cooling in labor market conditions is unmistakable. Job gains remain solid but have slowed this year.4 Job vacancies have fallen, and the ratio of vacancies to unemployment has returned to its pre-pandemic range. The hiring and quits rates are now below the levels that prevailed in 2018 and 2019. Nominal wage gains have moderated. All told, labor market conditions are now less tight than just before the pandemic in 2019—a year when inflation ran below 2 percent. It seems unlikely that the labor market will be a source of elevated inflationary pressures anytime soon. We do not seek or welcome further cooling in labor market conditions.

There are a few principles to highlight:

The information used to assess labor market conditions is complex. Powell names the following series in his assessment: the unemployment rate, layoffs, labor supply, hiring, job gains, vacancies, quits, and wages. That breadth is more necessary than ever due to the economy's unusual features since the pandemic and various data measurement challenges.

The comparisons are relative, not absolute. Unlike inflation, which has an explicit 2% target, the Fed believes that maximum employment—the highest level of employment that does not cause inflation—shifts over time due to factors like demographics that the Fed does not control. There are two relatives in his speech: the US labor market in August 2024 and the pre-pandemic (2018-19) labor market. The current labor market is markedly less “tight” than early in the recovery from the pandemic when labor shortages were a problem. Reducing the excess demand for workers was expected and partly the intent of the Fed’s higher rates. However, the labor market is now less tight than before the pandemic when inflation was below 2%. The Fed does not view further weakening as necessary to bring inflation down.

“We do not seek or welcome further cooling” is a substantially lower bar for cutting rates than Powell’s earlier criteria of a “significant weakening” in the labor market. The former concerns slipping behind the (very good) pre-pandemic labor market, and the latter concerns a recession. There is a wide gulf between those two outcomes, and with its confidence in disinflation, the Fed is shifting its support closer to maximum employment side of the mandate.

The rest of my post reviews some of Powell's highlighted indicators and explains what “further cooling in the labor market conditions” might look like.

The unemployment rate.

Normally, the unemployment rate is the key metric by which the Fed judges the labor market, especially the degree of slack (an excess of supply over demand). The unemployment rate of 4.3% in July would not necessarily raise concerns since it is still historically low and close to, if not below, many natural (or equilibrium) rate estimates. However, in the years before the pandemic, the Fed repeatedly underestimated how low unemployment could go without sparking inflation. So, rather being fixated on the level, attention is being directed to the change in the unemployment rate and whether that’s a sign of “further cooling.”

In the current environment, it’s important not to assume that any rise in the unemployment rate is evidence of cooling demand. As I discussed in my Bloomberg Opinion last month on the Sahm rule, it’s crucial to think about the supply of workers:

A rise in the unemployment rate due to weakening demand for workers gains momentum in recessions, which is why the Sahm rule has worked well historically. But a rise in the unemployment rate due to an increase in the supply of workers is different. The rate will decrease once the jobs “catch up” with the new job seekers and more workers allow the economy to grow more. The Sahm rule does not distinguish between these two dynamics, and can look more ominous when the labor force is expanding rapidly.

There are signs that stronger labor supply, not just weaker labor demand, helped push the Sahm rule past its 0.50 percentage point threshold. [See chart below.] Unemployed entrants to the labor force (new or returning) accounted for about half of the increase. That’s a notably higher share than in recent recessions, when most of the contribution came from unemployed workers who had been laid off temporarily or permanently. The current Sahm rule reading is likely overstating the weakening in demand and not at recessionary levels. Even so, there are risks. Recessions have occurred while the labor force is expanding, as in the 1970s, so the current episode would not be a historical outlier for the early stages of recessions.

That’s one simple way to look at changes in the unemployment rate—the reasons behind being unemployed. However, it does not settle how much of the current rise is due to decreasing labor demand or increasing labor supply since even a rise in unemployed entrants can reflect both channels.1

When interpreting the unemployment rate, the labor supply channel is clearly on the Fed’s radar. Powell shared a chart with the large, expected swings in the labor force relative to the pre-pandemic trend (according to the Congressional Budget Office). Millions dropped out of the labor force early in the pandemic, and it was not until mid-2023 that the labor force recovered to trend. Since then, it has continued to rise with a surge in immigration despite the ongoing aging of the population. Those swings were large and rapid, occurring within less than five years.

The changes in the supply of workers have been at least as profound as the disruptions to supply chains in the US economy in recent years. Demand-centric frameworks to interpret labor market conditions, like the Sahm rule, will fall short in these conditions.

The August unemployment rate is expected to tick down to 4.2%, with some of the temporary layoffs from July reversing. (Note: the geographic data do not support the claim that Hurricane Beryl drove the higher unemployment rate.) A steady or rising unemployment rate in August or the coming months would not necessarily indicate cooling demand if labor force participation also rose. Still, the increased supply of potential workers would reinforce the benefits of a stronger labor market, and the inflation risks would be low due to more supply. Regardless of the reason for a rising unemployment rate, the Fed would have support to cut. That said, a rising unemployment rate without increased participation or some other special factor would be cooling demand, raising the risk of substantial weakening and pointing to larger rate cuts.

Many more rates in the labor market to watch.

Powell’s summary included several “rates” other than the unemployment rate to judge labor market conditions. The rate of new hires, voluntary quits (excluding retirement), and layoffs as a fraction of total employment are all important indicators.

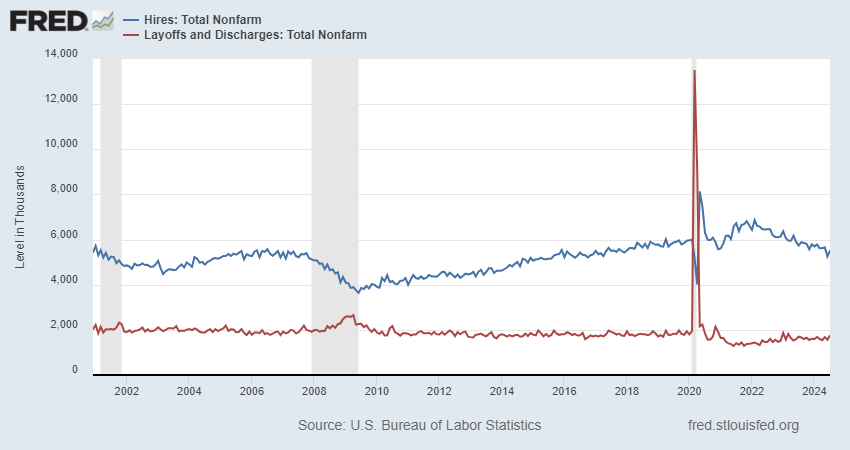

They also show why it is important not to look at a single metric in isolation. The hiring rate—which has fallen substantially in the past two years and is on par with its 2014 level when the unemployment rate was 6%—is arguably the most worrisome indicator in the labor market now. That contrasts sharply with the layoff rate, which remains near all-time lows. The tension almost certainly reflects memories of businesses’ struggles with labor shortages in 2021-22—the historically large layoffs early in the pandemic disadvantaged businesses when consumer demand surged back.

The ongoing uncertainty about the economic outlook and fears about a slowdown are showing up now as less hiring, not more firing. Some of that is normal. It’s a common misconception that layoffs drive recessions and rising unemployment. However, a large pickup in layoffs often occurs late in a recession. In contrast, hiring declines from the start. Note also how large the swings in layoffs and hiring have been since the pandemic. The slowing in hiring from very high levels in 2021-22 was to be expected, even though hiring tends to rise in recoveries.

Bob Hall, a well-respected macroeconomist and chair of the NBER’s recession dating committee, wrote in 2005, “The job-finding (or hiring) rate is the key variable in understanding the large fluctuations in unemployment.” He explored various economic factors like productivity, real interest rates, and wage-setting norms that might explain the variations in unemployment connected to job finding. Still, he emphasized that a specific recession would have some specific drivers.

The most recent Beige Book—another source of information for the Fed—had several supportive anecdotes on the hiring vs layoff tension, such as from the Boston District:

Staffing contacts said that job creation had slowed owing to increased caution in the face of economic uncertainty. Employers reportedly became more selective about workers’ qualifications and did not face substantial hiring difficulties. Restaurant and retail contacts even said that labor supply had improved somewhat, facilitating replacement hires. Nonetheless, certain positions, especially temporary roles, remained difficult to fill. Manufacturers reported moderate annual wage growth rates on average, although one said that merit increases put in place earlier in the year had been above average. With rare exceptions, firms did not plan to expand their workforces moving forward, but no major layoffs were planned either. Hotel industry representatives faced the possibility of a large-scale worker strike pending the outcome of upcoming contract negotiations. A workforce development contact expressed increased pessimism concerning job prospects for their trainees, as recent graduates had faced unexpected difficulties finding suitable jobs.

Or from the New York District:

Labor market tightness continued to moderate, with ongoing cooling in labor demand and increased labor supply across the District. Contacts at employment agencies noted hiring activity in both New York City and across upstate New York has slowed as firms are approaching hiring decisions with greater hesitancy. Hiring has shifted to be primarily for replacement, rather than growth, and with uncertainty pertaining to the presidential election ahead, many firms have put hiring plans on hold. It has become much easier to find workers, particularly for firms offering remote or hybrid work options. Still, some contacts from industries that require in-person work reported some difficulty finding skilled workers, particularly in the skilled trades. Multiple contacts reported that worker attrition has declined to exceptionally low levels, and job candidates are lingering on the market for longer.

And the Atlanta District:

Employment in the Sixth District increased modestly over the reporting period. Most firms continued to report improvements in talent availability. A few noted labor reductions, mostly in the form of cutting regular and overtime hours and, in a minority of cases, layoffs. However, several firms said that further weakening of demand could result in future layoffs. While many firms reported that they will continue to fill vacant positions, several noted that they were slowing the pace of hiring for the remainder of the year. Only a few indicated they would be staffing up in anticipation of future growth.

With lower hiring rates, we should expect to see a rise in unemployment. The rise may not be every month, but the underlying dynamic of cooling is in place, even if layoffs remain low.

Job openings are another key indicator of labor demand. They are often expressed relative to the number of unemployed (below) or relative to employment (the vacancy rate). They have figured prominently in the Fed’s thinking about the labor market.

In 2022, when inflation surged and labor shortages occurred, Fed Governor Chris Waller (with economic adviser Andrew Figura) argued that the labor market could “cool off” via far fewer job openings. At that point, there were over two openings for every unemployed individual. Waller’s appeal to the Beveridge curve was a pushback to a simple Phillips curve logic that substantially higher unemployment would be necessary to decrease inflation. In fact, by July 2024, job openings were down 37% from their peak in March 2022. With unemployment up 20%, there is now only about one job opening per unemployed. The current level is slightly below the pre-pandemic pacing and trending lower.

Jobs, jobs, jobs.

Job creation, central to labor market conditions, has slowed substantially in the past few years, largely reflecting a normalization of the labor market. It’s worth recalling that 20 million jobs were lost in April 2020, and even though many of them were temporary layoffs and recalled quickly, there was an enormous job gap to fill after the recession. The rapid recovery in jobs (below), albeit with large month-to-month swings, was unsustainable. Until recently, the Fed has viewed slowing in monthly payroll gains as welcome and necessary.

But that’s not true anymore. The payroll gains in July 2024 on a one-month (above) and three-month average basis (below) moved below the pre-pandemic pace. There is no sign of the slowing leveling out. Moreover, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics recently, the monthly estimates are likely to be revised to 68,000 per month from February to March 2024 at the next annual benchmark.

As I discuss in my latest Bloomberg Opinion piece, the revisions have a broad message as we try to assess labor market conditions:

That said, revisions do impose certain responsibilities on those using the data. It is easy to see how “datapoint-driven” decisions — an extreme version of “data driven” decisions where the exact number is the focus — could lead policymakers astray. Looking at averages across months, instead of a single month in isolation, can help reduce the dependence on one estimate. It’s also better to focus on the broad contours of the data instead of a specific number. Applying that approach to the monthly payroll estimates — both the latest issue and the revisions of previous ones — shows that the basic story of a cooling labor market is mostly unchanged.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s statement last month that the bank does not “seek or welcome further cooling in labor market conditions” fits this approach. It also expands the analysis to more than payroll gains. In characterizing the labor market as “cooling,” Powell also discussed the unemployment rate, layoffs, hiring, job vacancies, quits and wages. Each estimate is subject to revision, but all are unlikely to be off in the same direction.

August payrolls are expected to rebound slightly from the soft July print of 114,000. The market reaction, especially initially, to any surprises (or even consensus of 160,000) will likely be outsized. Job creation is crucial to the labor market, but one payroll print is not definitive on job creation, let alone labor market conditions.

In closing.

After four and a half years of unusual and severe disruptions, the US economy has nearly achieved the soft landing of low inflation, low unemployment, and solid growth. Reductions in the federal funds rate are crucial to the final stage. The appropriate speed and magnitude of rate cuts will depend heavily on labor market conditions and our ability to interpret them in real-time. Now is not the time to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory with a misguided reading of the labor market.

In an alternate approach to measuring the Sahm rule, Wouter Beeckman first used a Structural Vector Auto Regression to remove labor supply shocks from the unemployment rate. The identifying assumption is that an increase in labor supply increases unemployment and GDP simultaneously while lowering prices and real wages. He found that the supply-adjusted Sahm rule has risen but was well below recession levels.

“However, in the years before the pandemic, the Fed repeatedly underestimated how low unemployment could go without sparking inflation.”

That’s backwards. Rather:

However, in the years before the pandemic, the Fed repeatedly underestimated how high inflation needed to go to achieve maximum employment (of all resources).

I am agreeing with your substantive point, the Fed correct to stimulate demand/reduce the EFFR, and indeed should have done so sooner.

"maximum employment -- the highest level of employment that does not cause inflation"

This is a mistaken way of putting it. Levels of employment do not cause inflation and disinflation; it's the other way around. The Fed causes inflation. labor market touches all sectors of the economy and it's state is non-exclusively informative of how close the economy is to full employment of all resources, to instantaneous maximum real income. But it is the inflation rate that achieves the latter that the Fed ought to be seeking not any one metric of the labor market.