It's 2022, not 1972

The talking heads who use the 1970s as a guide are dangerously stuck in the past. Instead, we must face the present moment with its challenges and advantages.

The obsession with the 1970s in the debates about the Fed is a massive waste of time and creates dangerous blind spots. Everywhere you turn, the doomsayers say, “It’s the 1970s again; the Fed has no choice but to cause a recession.” If we look at the data and the Fed’s thinking then and now, it’s clear the past is not the present.

It’s no time for the Time Warp.

Gloom and doom.

The 1970s are everywhere. Here’s Larry Summers:

I was arguing through 2021 that the right analogy was the Vietnam War period, when we used very expansionary fiscal policy, did not apply monetary restraint, and pushed inflation up very, very substantially. I think that now looks to have been a reasonable description of what happened in 2021. - February 4, 2022

And the history [of the 1970s] is that if you look at the overall path, the poor are worse off once you go through that whole process than they would’ve been if you kept things [inflation and wage growth] stable all along. That’s why the Fed’s new woke rhetoric in 2021 was so dangerously misguided. - April 4, 2022

Many other experts agree with him, and history suggests the Fed is in tough spot.

Let’s start with some facts.

One year of higher inflation after a decade of low inflation is not the same as a decade of high inflation.

The fast recovery from the Covid-recession is good for American families and businesses. Consumer spending is back on trend even with the higher prices. Same with business investment. In contrast, the Great Recession was terrible.

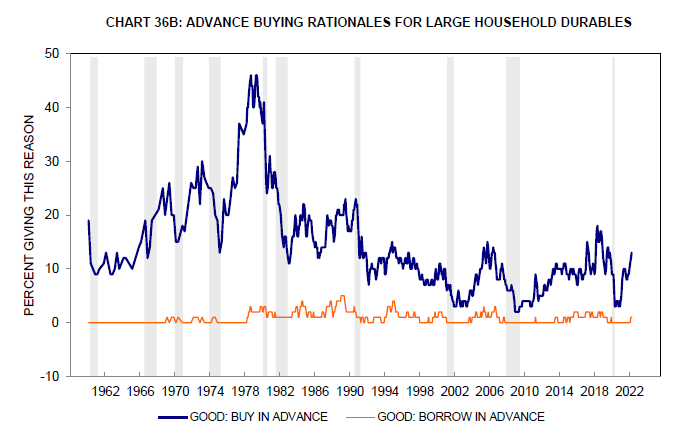

Consumers are not buying in advance because they expect higher prices, unlike in the 1970s. There are no signs of consumers adopting an inflationary mindset.

Source: Surveys of Consumers. The University of Michigan.

Let’s focus on the future.

We must be vigilant. The Fed must act to bring inflation down. It is! And it has the full support of the White House and Congress. No guarantees of success. People’s beliefs can change quickly. Feelings matter. And the world has been cruel the past few years. That said, it’s not time to throw in the towel and accept a recession. No!

Below the paywall, I explain that the Fed’s thinking and actions in the 1970s are not comparable to the current crisis. We have learned many lessons from the past, and it’s clear that Fed officials are applying those lessons as best they can today.

I appreciate your support of my Substack. Please send me suggestions or questions.

I understand why our inflation debates are stuck in the 1970s. Recessions are rare events, especially severe ones. The bottom falls out; all models break, then we recover.

However, the mix of policy responses and developments in the world differs each time. Past inflation might be a good place to start; it’s a dangerous place to stop.

It’s essential to understand how monetary policy has improved since the 1970s. Jay Powell is not Arthur Burns. The Fed’s tools and thinking are much better today.

Know thy history

There is only so much we can do with time series charts—context and institutions matter. So, let’s dig in. I recommend the Federal Reserve History series, which looks back on different policy moments as a place to start. For example:

The Great Inflation [1965-1982] was the defining macroeconomic period of the second half of the twentieth century. Lasting from 1965 to 1982, it led economists to rethink the policies of the Fed and other central banks.

It was, according to one prominent economist, “the greatest failure of American macroeconomic policy in the postwar period” (Siegel 1994).

But that failure also brought a transformative change in macroeconomic theory and, ultimately, the rules that today guide the monetary policies of the Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world. If the Great Inflation was a consequence of a great failure of American macroeconomic policy, its conquest should be counted as a triumph.

The FOMC meeting transcripts are also insightful. There are records back to 1936. The discussions during the Great Inflation are fascinating. Here’s then Fed-Chair Arthur Burns at the July 1977 FOMC meeting. Note inflation then was 6.6 percent, up about 1.5 percentage points from six months earlier. Burns’ conclusion:

Gentlemen, we’re faced with a very hard decision. Speaking personally for a moment, I wish I could join my colleagues who were inclined to move toward somewhat lower growth rates [in the money supply]. I wish I could--temperamentally, yes; that’s what I would prefer to do. But I do have an obligation to this Committee and to the System as well as to the country. I’ll have to testify before the Committee, I will have to defend whatever this Committee decides.

… If I could argue with conviction that that would put significant downward pressure on the price level, you see, yes, I would be in good shape. But I can’t. I can’t argue that. It may put some downward pressure on prices; it may put some downward pressure on activity. Over the longer run, yes. I could argue with respect to the effects on the price level.

There’s so much to unpack there. And so much at odds with the Fed’s approach to higher inflation today. The vagaries in communication policy then are notable. Here’s January 1973:

Mr. Mitchell asked, with respect to the upper limit of 6-3/8 per cent for the funds rate, whether the Chairman was suggesting that the Desk probe toward that level immediately.

In reply, Chairman Burns said he would not want to see the Desk take steps that would firm money market conditions on the first day after the Committee's meeting, thereby giving clear signals that might benefit market participants; he preferred to maintain a degree of uncertainty about the course of policy.

Compare that to Jay Powell and numerous Fed officials clearly telegraphing a 50 basis point move at the next meeting in May and “expeditious” increases. The last thing the Fed wants to do is inject uncertainty into the world now. Smart.

On the inflation dynamics: a fact lost in the current 1970s obsession is the different labor market institutions. A wage-price spiral via cost-of-living adjustments was baked into the structure of the economy in the 1970s:

In the case of contracts that contained cost-of-living provisions, however, average wage increases this year would depend on the behavior of prices. It was of great importance for wage developments in 1973 that the number of workers covered in contracts to be negotiated was substantially larger than in 1972 and that many of the negotiations were in important industries.

In 2021, 10% of workers were in unions. That’s half the level in 1983. Only 6% of private-sector workers are unionized today. Without unions, most workers do not have the bargaining power to get wage increases that predictably outpace inflation. A union at one Amazon warehouse last month does not move the needle.

In addition, for several years in the 1970s, the Fed was under pressure from the White House and Congress to push economic growth faster.1 And as the Fed kept interest rates low, the federal government did massive spending. Then that world collided with two major oil shocks when we were more dependent on foreign oil.

By the close of the 1970s, it was clear that something had to change:

As businesses and households came to appreciate, indeed anticipate, rising prices, any trade-off between inflation and unemployment became a less favorable exchange until, in time, both inflation and unemployment became unacceptably high.

By the late 1970s, the public had come to expect an inflationary bias to monetary policy. And they were increasingly unhappy with inflation … During this time, business investment slowed, productivity faltered, and the nation’s trade balance with the rest of the world worsened. And inflation was widely viewed as either a significant contributing factor to the economic malaise or its primary basis.

Again, look at my charts above. We are not living through stagflation.

Even adjusted for inflation, consumer spending is roaring ahead, as is business investment. Consumers do not expect inflation to be persistently higher. The burst of the expenditure now is not spending-in advance. It’s making up for the pent-up demand due to Covid and decades of low wages. Most importantly, while we need to keep an eye on the current situation and not be complacent, one year is not a decade.

The Fed is not asleep at the wheel.

Wrapping up

Our debates mired in the 1970s come at a cost.

The Fed faces new challenges as it moves to tame inflation. Paul Volcker was not making policy during the global pandemic and war in Europe that disrupted both supply and demand.

We must discuss today’s challenges and advantages. Policy experts must help forge solutions instead of cheering on a recession or looking back to the 1970s.

On a personal note, I was minus-four years old in 1972, though I do love Rocky Horror Picture Show. Here’s me and a friend in Madison in 1995.

Reading the summaries of the Fed meetings in the 1970s, it is striking how much time is spent on fiscal policies and how they interact with Fed policy. It’s true that the Fed keeps an eye on fiscal policy and its potential effects, but it’s not involved in the deliberations as was the case in the 1970s. That’s another lesson learned. Independence is crucial.

You present data from the long-running UM consumer survey with respect to the impact of inflationary expectations on advance purchases of large durable goods. The data suggest that the peak period for "buy it now 'cause the price is going up soon" was 1975-1980.

I'm trying to reconcile that with my own memories of the period ... but as a graduate student who never was employed full-time/year-round before late 1980, I was too poor to buy any consumer durable goods during that period! And for many people the biggest inflationary impact came in food and gasoline prices, which by definition are not durable goods.

The Fed histories you cite frame the years 1965 to 1982 as one period. That's hindsight. I suspect that for most working-class people this was less one period than a series of shocks: Nixon's wage-price controls in 1971, then the two oil embargoes in 1973 and 1979. It was the impact of these shocks that wore people down to the point they were willing to accept Volcker's medicine, which was in essence an assault on the power of organized labor to keep up with inflation.