Inflation: it's "complicated"

What's been causing inflation is important. Get it wrong, and we get the wrong policies. And we learn the wrong lessons for the future.

Today’s post is my reaction to “What Caused the U.S. Pandemic-Era Inflation?“ by Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard. The errors here are my own. Go to the authors, too: here’s the paper, news coverage, a video, and a tweet thread.

My summary: Bernanke and Blanchard argue that supply disruptions and commodity price swings due to Covid and especially the war in Ukraine have contributed substantially to inflation, The strong labor market and the extra demand for goods that were often in short supply led to inflation too. Both inflation optimists and inflation pessimists were right and wrong about inflation in different ways. It’s complicated. The question now is how much the labor market (and the demand supports) continues to push up inflation, Getting ‘stuck’ above its 2% target would be a bad outcome and in line with the inflation pessimists. There’s something for everyone in their paper, it ain’t over, and it’s important.

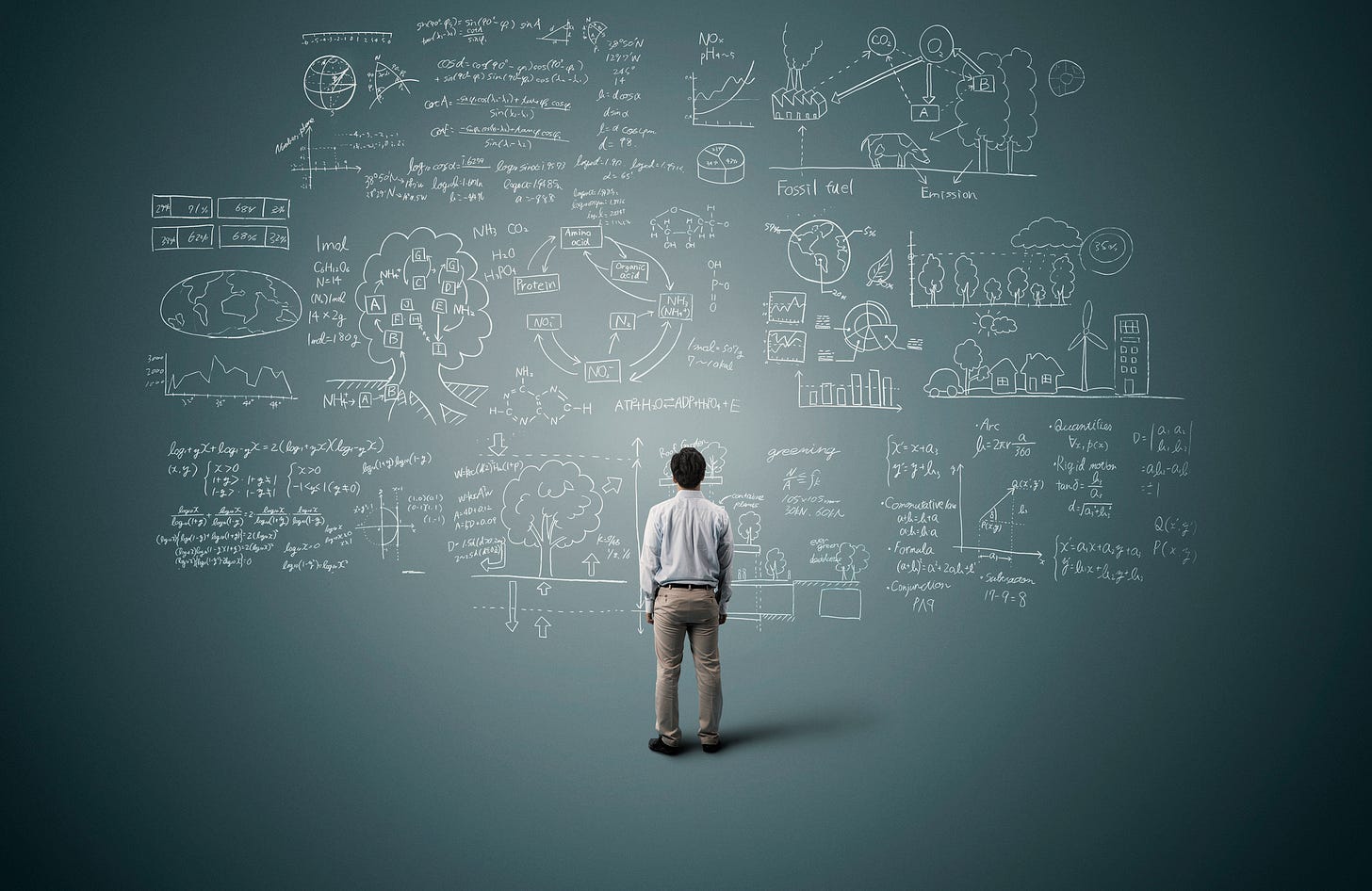

Putting words into pictures, here is their Money Chart:

Shortages (in yellow), food prices (light blue), and energy prices (dark blue) explain the spikes in inflation more than the labor market (red). Even so, as the supply-side contributions wane, those from the labor market have persisted and could keep inflation staying elevated.

Bernanke and Blanchard’s model-based findings align with the statistical decomposition by Adam Shapiro, an economist at the San Francisco Fed. Of course, there is research that comes to the opposite conclusion.

In my opinion, it’s impossible to look at inflation in recent years and say it’s only demand and then blame the American Rescue Plan and the slow-to-lift-off Fed. Likewise, it’s impossible to say it was only supply. This debate among macroeconomists matters to everyday life because it informs the Fed’s decisions and Congress,’ especially if we were to have a recession.

Workers have the upper hand, or do they?

A key aspect of their analysis is how strong the labor market is. And what’s driving wages? Nominal wage growth depends on three elements:

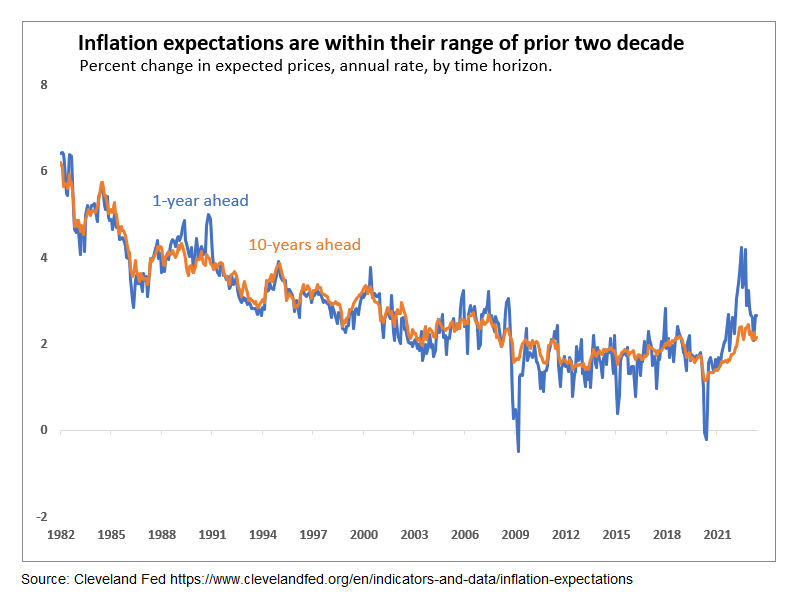

Inflation expectations. (Cleveland Fed 1-year and 10-year).

Aspirational real wage to catch up to past inflation.

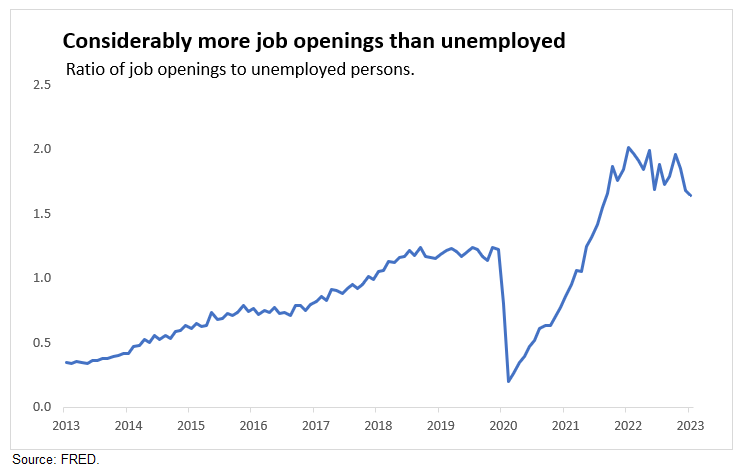

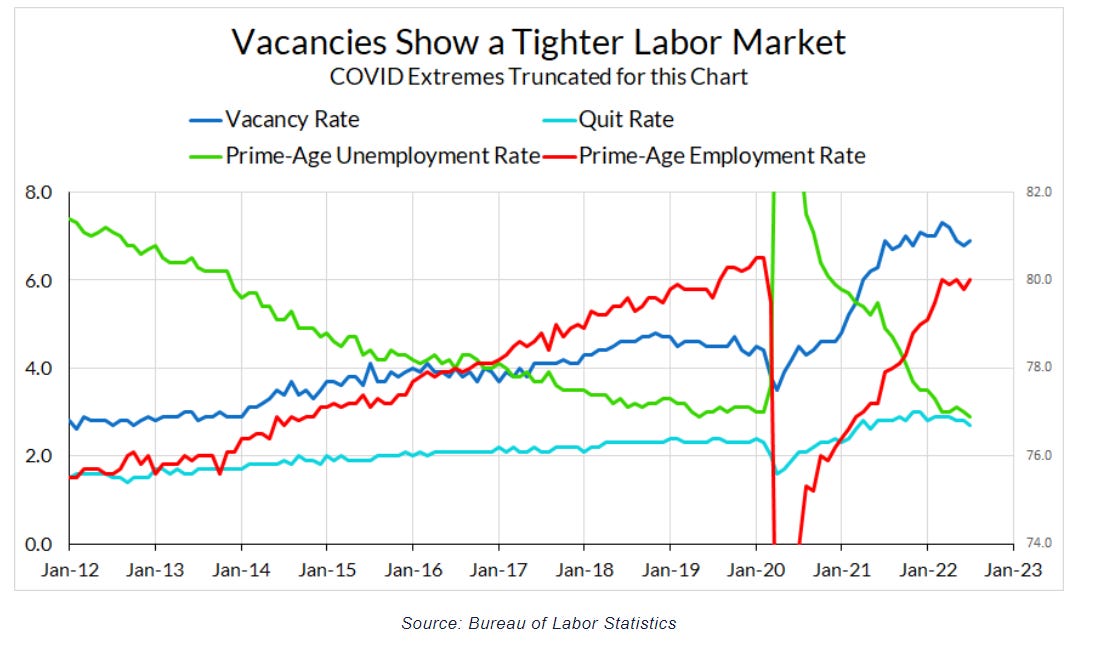

Labor market tightness (job opening / unemployed).

Bernanke and Blanchard use the vacancy rates as the ratio of job openings to unemployed persons. The latest reading is 1.6, down from 2.0 a year ago but well above its pre-Covid levels. They characterize it as a tight labor market.

But is that a very tight labor market? Preston Mui of Employ America says no:

The empirical sources for vacancy data are shaky at best. The threshold for reporting a vacancy in official statistics is low, making it difficult to infer search intensity from the raw number of vacancies, potentially inflating the number of observed vacancies. Changes to the cost of job posting and job searching – especially on online job boards – make comparisons across time difficult …

While labor market indicators show a strong recovery from the pandemic recession, vacancies-based metrics portray a far tighter labor market than other indicators. ~ Preston Mui

Rather than lean heavily on the vacancy rate, it is best to track several measures. Vacancies point to more tightness than nearly every other measure.

This is not an academic exercise. The Fed focuses heavily on vacancies and points to them as a reason to hike rates aggressively. But the Fed using vacancies to guide its policy decisions risks doing too much and causing a recession unnecessarily.

Bernanke and Blanchard also investigated whether workers “catch up” on past inflation as a determinant of wages. They describe catch-up as:

The existence of a catch-up term implies that, in their bargaining with employers, workers seek to be compensated for last period’s unexpected inflation. In other words, to the extent that workers’ expectations or focal points (or those of their institutional representatives) influence the wage bargaining process, the economy exhibits a degree of real-wage rigidity. ~ Bernanke and Blanchard

“Catch up” or “Aspirational real wage” is not standard in macro models. But it is a useful addition here, given the concerns about worker bargaining power, creating a wage-price spiral. But when they estimate the model, catch-up does not affect wages.

Inflation expectations lookin’ good.

Inflation expectations did not de-anchor; that means the level is now within range in recent decades, albeit toward the top end of the range, and did not move much in the past three years. And that’s very good, as far as the Fed is concerned. Had expectations moved up persistently, we would have more than a 5% fed funds rate.

The inflation expectations that Bernanke and Blanchard are from the Cleveland Fed. This long-run measure is well anchored (and has been throughout and the short-run measure has come back down in line with the CPI inflation retreating.

Other standard measures of inflation, like the Michigan Survey, tell a similar story—anchored expectations. Inflation remains elevated, and there is no reason to declare victory. Inflation expectation is a reassuring sign that markets and consumers believe we will get inflation back to normal. Whether it’s due to the Fed or not, people are expecting high inflation now to be transitory. The timeline got stretched out, but beliefs have not changed. And that’s good for fighting inflation.

What’s missing?

Bernanke and Blanchard’s model allows for worker bargaining power by modeling a “catch-up” concept. But there is nothing on market power. It’s important to watch out for wage-price spirals, which occurred in the 1970s and pushed inflation up. But what about price-price spirals? What about the role of profits?

Isabella Weber has been at the forefront of how crises like the pandemic and the war in Ukraine allow firms to raise prices aggressively, even more than their rising costs.

We argue that the US COVID-19 inflation is predominantly a sellers’ inflation that derives from microeconomic origins, namely the ability of firms with market power to hike prices. ... Rising prices in systemically significant upstream sectors due to commodity market dynamics or bottlenecks create windfall profits and provide an impulse for further price hikes.~ Isabella Weber

There’s more in my recent post on price-price spirals:

Price-price spirals take us for a spin

Last week we learned that consumer price inflation, while still somewhat elevated, is coming down. At the same time, unemployment is holding steady at its fifty-year low. The sources of inflation during the past few years and its path going forward are debatable, as are the best policy responses. In a recent interview, I was asked how much profits are c…

Bernanke and Blanchard briefly discuss the “markups” of price over cost.

The collision of high demand and limited supply in some sectors can account for at least some of the increase in markups observed during the pandemic period. While other factors no doubt influenced markups, including for example the fiscal transfers that directly affected demand in product markets, at least in this simple specification we do not find that including these factors is needed to explain the behavior of pandemic-era inflation. ~ Bernanke and Blanchard

That explains some, but not all, of the rise in markups. That leaves reasons to keep studying markups since the pandemic began. It’s fascinating how much that door has been opened in the past few years. See this excellent piece by Emily Peck.

In closing

Putting the pieces together. Inflation is complicated.

According to Bernanke and Blanchard, no single factor has pushed up inflation. Instead, it’s been a series of evolving factors. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine, policy responses, a strong labor market, and changes in behavior all matter for inflation. Even with a relatively simple model, Bernanke and Blanchard show us how complicated inflation is. That’s an important message for us to hear.

Bernanke and Blanchard’s summary is a good place to close it out:

We answer the question posed by the title by specifying and estimating a simple dynamic model of prices, wages, and short-run and long-run inflation expectations. The estimated model allows us to analyze the direct and indirect effects of product-market and labor-market shocks on prices and nominal wages and to quantify the sources of U.S. pandemic-era inflation and wage growth. We find that, contrary to early concerns that inflation would be spurred by overheated labor markets, most of the inflation surge that began in 2021 was the result of shocks to prices given wages, including sharp increases in commodity prices and sectoral shortages. However, although tight labor markets have thus far not been the primary driver of inflation, the effects of overheated labor markets on nominal wage growth and inflation are more persistent than the effects of product-market shocks. Controlling inflation will thus ultimately require achieving a better balance between labor demand and labor supply. ~ Bernanke and Blanchard

And here’s the video, including a discussion by Jason Furman.

Addendum: In reading their paper, I came to the description of “complicated” because of the different sources: supply and demand at different times. It’s “nuanced” may be better Blanchard sees underlying inflation as largely due to strong demand. Read his Twitter thread

to explain it.I stand by. “it’s complicated,” but “it’s nuanced” in the timing of the shocks might be closer in spirit to them. I told you there’s something for everyone in their paper.

When profit driven inflation led CEOs to boast to their shareholders about their great management of lower production output yet higher profits from higher prices of course Bernanke and company had to ignore that. It’s like stepping over dog shit on the sidewalk and pretending it’s not there

Kudos at raising the issue of oligopoly price gouging as a possible significant cause of the current cycle of inflation and softly pointing out that B&B have a noticeable blind spot on this issue. The problem exists as any consumer with a wallet can see, but is overlooked in officialdom because (1) the Fed has no responsibility or authority over this dynamic and (2) Congress and the White House, even if they had the political will, would need years to correct the major business consolidations throughout the consumer economy and would experience such lobbying pushback that the real chance of fixing this contribution to inflation is actually (and unfortunately) very small.