Inflation, Inflation, Inflation

Last week, we learned more about inflation. It was good news, but not good enough for the Fed and certainly not for the American people.

Programming note: I will be in New Zealand next week to kick off the Zealand Treasury’s lecture series, ‘Fiscal Policy for the Future.’ My talk is on automatic stabilizers. You can sign up to attend virtually or in person. Monday, June 10 · 9:30 - 11 pm EDT.

In today’s post, I discuss the latest inflation data for April. Then, I argue (again) that the anger about inflation goes well beyond its economics, and finally, I share new research on the sources of disinflation.

Inflation is coming down. It’s time to cut.

Here’s a short clip from my interview on CNBC’s Squawk Box on Friday, right after the PCE inflation report was released.

I explain why the Fed has a case (not in the clip) to cut now. It’s the dual mandate of stable prices and maximum employment. With the disinflation so far and moderating the labor market, the upside risks to inflation and the downside risks to employment are about as likely. People, including Fed officials, keep talking about a possible rate hike due to higher-than-expected inflation, but no one talks about a big rate cut in one meeting due to a recession. ‘Higher for longer’ can turn into ‘higher for too long’ if the Fed is not careful.

A minor note on the data: Core PCE inflation in April was 0.249%, which rounds to 0.2%. If it had been 0.001 percentage point higher, it would have rounded to 0.3%. As I wrote earlier, our statistics do not have that degree of precision, though I greatly appreciated the optics of it. The big picture is that inflation has softened over the past nine months, which is a relief. Or is it?

Inflation is more than inflation.

My new Bloomberg Opinion piece expands on my latest post here on anger about inflation. Right off the bat, I dispel the notion that the problem is words:

According to Merriam-Webster, inflation is “a continuing rise in the general price level.” When Americans complain that prices are high, they are implicitly comparing prices now to those of 2021, when inflation took off. When economists point out that “inflation” is lower, they are implicitly comparing prices now to 12 months ago.

Both time frames are informative, and prices rose in both periods, so both are inflation. Redefining “inflation” is unnecessary and counterproductive when all we need to do is make the implicit parts explicit.

Economists should be clearer, but better communication will not resolve the debate over why people are so angry about the economy. Why? It’s not economics.

Anyone who pushes back and tells me there are homeless, housing is unaffordable, inequality is massive, interest rates are high, groceries are a lot more expensive, etc.—all of which are sadly true—must then explain the following from my piece:

One more puzzling development now is the disconnect between people’s assessment of their own finances and their assessment of the US economy. The Fed’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking shows that clearly.

Last fall, 72% of respondents said they were financially “doing OK” or “living comfortably.” That’s relatively close to pre-pandemic levels. However, when asked about their local economy, only 42% said it was “good” or “excellent.” And then, when asked about the national economy, there was a big divergence: Only 22% said it was “good” or “excellent.” That’s a 50-percentage-point gap — among the same people. Moreover, the gap widened in 2020 and has been relatively stable since.

What possible economic explanation exists for the gap between the perceptions of one’s finances and the US economy—the blue and gray lines? It widened in 2020, but inflation reared its ugly head in 2021. Many of the other structural problems were with us before the pandemic. For the past four years, most people view their finances as at least okay, but few see the economy that way. There is something real there, but it’s not economics. My other ideas:

It is hard to pin the divergence in 2020 on inflation that arrived a year later. Something happened, surely — but the extra gloom likely goes beyond economics. It may be trauma from the pandemic upending our lives, social media amplifying what was already a bias toward negative news, a hyperpartisan environment, geopolitical events, or fears about what comes next.

I am not the only one struggling to untangle the anger at the economy. Last week, the New York Times had a symposium titled” Why Are People So Down About the Economy? Theories Abound.” Here is a recap of the contributors:

Kyla Scanlon: The higher price levels weigh on people, and knowledge gaps could contribute. In a recent survey, most Americans thought (incorrectly) that the US economy was in a recession.

Raphael Bostic: Prices and interest rates are too high.

Jared Bernstein: It takes time for the negativity of higher prices to fade even after wages catch up.

Loretta Mester: Wages have not caught up with prices. [Note that depends on the wage data.] Higher home prices and interest rates put the American dream of owning a home out of reach.

Larry Summers: Interest rates are high.

Charlamagne Tha God: People are living paycheck to paycheck and have lost their sense of financial security before Biden took office.

Susan Collins: Inequality has widened with some people much better off, like homeowners, and much worse for others, like borrowers. Also, greater post-pandemic anxiety could be playing a role.

Aaron Sojourner: The tone of the economic news has been more negative than the economic events would have normally predicted.

With one exception, I don’t see anything explaining the gaps in the blue and gray lines. Several would help explain why fewer people said they are doing at least okay financially in recent years. That makes sense since higher prices do cause hardship for some. (Though the bigger paychecks for many should soften that blow.) What about the gap between one's finances and the national economy? Sojourner’s explanation could be part of it. Media is in my list above, but that’s not an economic reason.

The NYT piece and the debate are basically a bunch of economists offering up theories. That’s not who we need to hear from. Here’s how I wrap my piece:

Words are not the problem. Nor are economists’ tools especially well-suited to sorting out non-economic explanations. So maybe the best way forward is fewer words from economists, less argument over the meaning of common economic terms, and more discussion about all the non-economic reasons for our gloom. That’s my hope.

“Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” not.

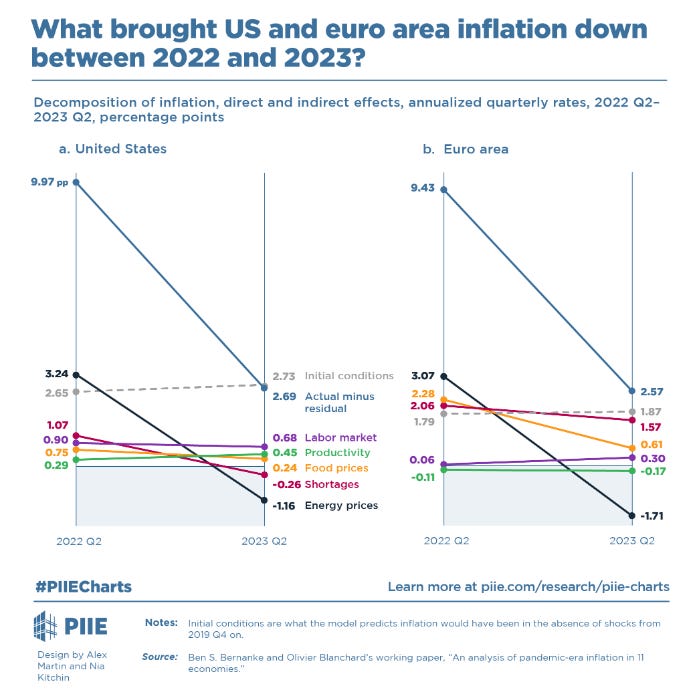

An important conversation in the coming years will be trying to understand the burst of inflation and rapid disinflation during the past four years. One early contribution is Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard’s new research note and accompanying working paper investigating disinflation from 2022:Q2 to 2023:Q2 in the United States and Europe. Reminder: the fact that inflation came down so much without slow growth (or even a recession) does not fit the standard story well.

Here is their summary and main chart:

The price shocks were especially pronounced in energy and food. Initially low energy prices in 2020 kept inflation at bay but spurred inflation as they rose in 2021 and most of 2022. Subsequent declines in energy prices in the United States and the euro area have led to declines in inflation more recently. Food price shocks have followed a different pattern: Their contribution to inflation was small until 2022, then consistently significant in 2022 and even more so in 2023. Supply shortages in general continue to contribute significantly to inflation in 2023 Q2 but less so since peak inflation in 2022 Q2.

I agree that supply shocks like energy prices, food, and supply shortages have been crucial to the inflation cycle. Their decomposition through the end of last year would be useful, too, when we saw continued disinflation. Of course, we will need to see the full cycle and many other analyses like theirs to get the full picture.

I very much endorse Bernanke and Blanchard’s closing:

An encouraging finding is that there is little evidence, in the United States and also other economies, that a wage-price or price-wage spiral emerged comparable to the high-inflation episodes of the 1970s, when increases in the prices of oil and other commodities led to demands for higher nominal wages, which fed on each other. The debate over whether the inflation spike of 2021–22 was temporary ("Team Transitory") or long lasting ("Team Permanent") continues without full resolution. Team Transitory was right that shocks to prices (e.g., for energy and food) would have short-lived effects on inflation, but it did not anticipate that there would be such a long sequence of shocks, leading to an extended period of inflation. Team Permanent was right to worry about labor market tightness but significantly overestimated its likely contribution to inflation early on.

There are many lessons about inflation from this cycle. Knowing everyone was wrong about something will hopefully encourage us to listen, reflect, and improve.

In closing.

Inflation is at the center of multiple debates right now. What should the Fed be doing to reduce inflation? How are people handling higher prices? Can inflation explain the anger at the economy? What will we learn from this mess so we do better next time?

We won’t answer all these questions this year or probably ever. It’s complicated. Some of this is economics, and some of it is not. All of its important.

This is what your excellent post inspired me to post in turn:

Inflation: Policies and Perceptions

https://stayathomemacro.substack.com/p/inflation-inflation-inflation?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=280281&post_id=145230218&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=8ylpe&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

Sahm has, as usual, an informative post on … wait for it … inflation …😊 The post fundamentally deals with two issues.

a) What the Fed did, did not do should and should not have done and should do now about inflation and employment.

b) Why people are more unhappy about “inflation” and “the economy” than they are about their personal finances

I have less reason to have a valid opinion of the latter than the former, but I will take a shot anyway as I see a link between the two that Sahm does not mention.

On the first issue, Sahm endorses the Bernanke-Blanchard story

https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/2024-05/wp\24-11.pdf?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

of Inflation being caused by negative supply shocks and a residual of other things. [Comin, Johnson, and Jones

https://www.nber.org/papers/w31179

come to the same qualitative conclusion but with a better, sectorally disaggregated model.] Neither B&B nor CJJ explicitly model Fed policy in arriving at these outcomes, however. This leads Sahm, implicitly I think, to blanketly endorse Fed actions. This is not necessarily wrong, but neither model considers demand shocks as consumers shifted massively from services to goods and then back as concern about COVID waxed and waned. This means that the models and Sahm cannot distinguish how much of Fed-engineered inflation was a) necessarily to deal with supply shocks, b) was necessarily to deal with demand shocks, and c) may have been in excess of what was needed for a) and b). [I discuss B&B and CJJ this at:]

https://substack.com/home/post/p-145235739?source=queue

and

https://thomaslhutcheson.substack.com/p/pandemic-and-inflation

In turn, this leaves Sahm’s position (and mine) that the Fed should now be cutting the EFFR, conceptually ungrounded.

An this is where I try to link the Fed actions to public perceptions.

The Fed has not been transparent in what it was trying to do: engineer enough inflation to allow the economy to adjust to shocks. I should be explicit, explaining that some part of the inflation it engineered was necessary to keep the economy fully employed and, if that’s what it thinks, admitting that it made mistakes in allowing too much inflation to go on for too long. Better understanding of Fed policies ought to diffuse at least some of the discontent with inflation and lead to the perception tat te economy is being better manages than previously thought.

[Standard bleg: Although my style is know-it-all-ism, I do sometime entertain the thought that, here and there, I might be mistaken on some minor detail. I would welcome comments on these views.]

It may be helpful to remember that the original name for the field that we now call "Economics" was "Political Economy." Frankly we would all be better off if the field had remained securely rooted in its origins in the Humanities (which among other virtues required it to respect the other branches rather than engaging in an arrogant and sordid sort of academic imperialism) rather than wandering down the epistemological dead end of its pretentions as a "science."