A boring Fed is the new Fed

Don't expect more surprises from the Fed. It's back to the standard playbook of small increases and then hold steady until inflation moves down sustainably. That will likely take more than this year.

Today’s post on the Fed is mainly for paid subscribers. The Fed will likely be boring for a while, doing precisely what it says now, for better or worse. What’s in store for the economy is as exciting and hard to sift through as ever.

After two years of an exciting Fed—in 2021, holding rates at zero even as inflation shot up and then in 2022 rapidly raising interest rates to catch up—we are back to boring. For this year, the Fed has charted a more standard course: 1/4-point fed funds rate increases for a while and then holds steady the rest of the year. The Fed’s done a lot. It will be patient, watch the data, and be reluctant to declare victory on inflation.1

Wait and see and worry.

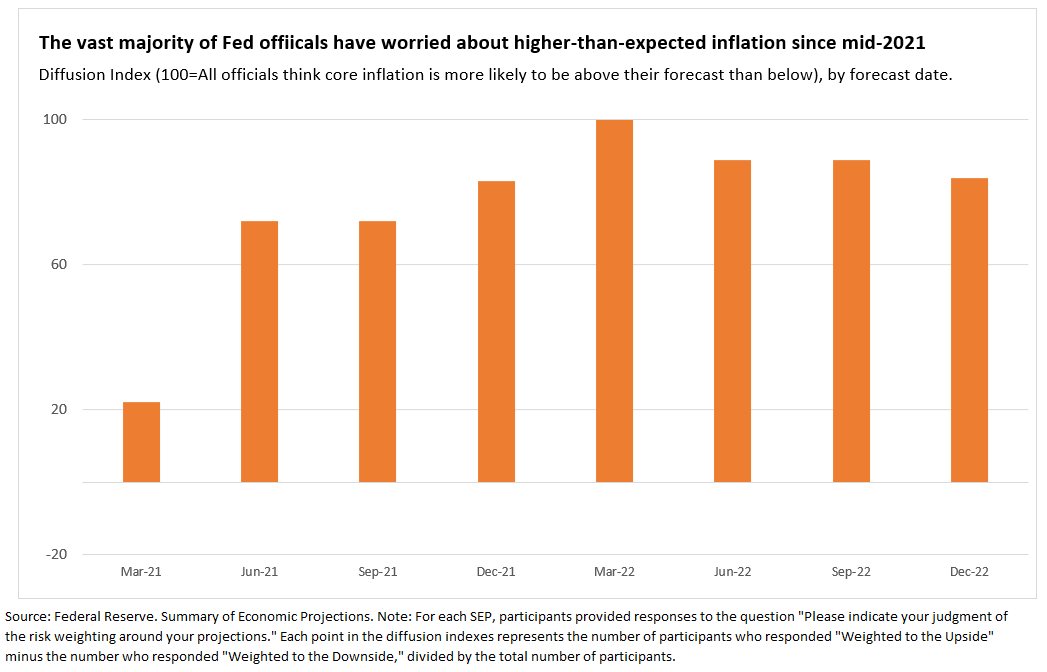

The Fed will need to see a lot of good news on inflation to shake it off its current path, and especially for it to start cutting rates. Bad news on unemployment is not sufficient. For almost two years, even as Fed officials ratcheted up their inflation forecasts and then raised the federal funds rate over four percentage points within nine months, the vast majority worried—as shown in the Summary of Economic Projections—that inflation would come in higher than their forecasts rather than lower. It repeatedly did. It will take several months of better-than-expected inflation data to calm those fears fully. Three months or even six months more is not enough.

Getting to a place where the Fed sees the risks around inflation are balanced to the upside and downside is important. Recall the Fed is not trying to get 2% at some magical moment in time; its longer-run goal is 2% “over time” in a sustainable way:

The Committee judges that longer-term inflation expectations that are well anchored at 2 percent foster price stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhance the Committee’s ability to promote maximum employment in the face of significant economic disturbances. In order to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at this level, the Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.

It’s not so much whether inflation comes in below the Fed’s 3.5% core inflation forecast for 2023—as I think it likely will—but how sustainable is it? A summary of Vice-Chair Brainard’s excellent speech last week: “inflation: it’s complicated.” With so many possible factors—some persistent and some temporary—it will be hard this year to make the definitive case that inflation is on a clear path back to a sustainable 2%.

The Fed is determined not to be head-faked again. It won’t cut until it’s confident about the lower inflation. That level of confidence is unlikely this year. If a recession comes or the market slides further, don’t expect the Fed to come to the rescue.

Below the paywall, I discuss why ‘Team Transitory’ is likely back at the Fed in 2023, but this time viewing lower, not higher, inflation as temporary. In addition, I describe the Fed’s framework for inflation as laid out in a newly released staff memo in 2017. It helps make sense of the Fed’s rate approach to and messaging on inflation during the past two years.

Team Transitory turned on its head.

In 2021, as goods prices shot up from Covid-related supply-chain disruptions, the Fed described the high inflation as “transitory” and thus did not raise rates. This year, expect the Fed to view lower-than-expected inflation as transitory (without using the word). As was the case on the way up, it will be hard to know which factors are driving inflation on the way down. Some factors will provide temporary, not sustainable, relief. The Fed’s big increases in interest rates since the spring of 2021 will help reduce demand and take pressure off inflation, though how much and when is uncertain. The Fed will be cautious.

One example of some temporary relief on inflation is the large declines in goods prices as supply chains unsnarl and consumer demand rebalances to services. This dynamic has been essential for lower inflation in recent months but is unlikely to remain as large. And as a result, it will contribute to volatility in core inflation early this year. Not every month is going to be a good one for inflation. It never is.

Another example is housing services. Recent declines in spot rents passing through to CPI housing services later this year, due partly to Covid disruptions easing and construction catching up with demand, aren’t going to be sustainable. As with goods prices, reversing some of the outsized increases in these categories will be welcome, and some of the lower inflation in housing costs due to less demand will be more persistent. But knowing how much won’t be clear until late in the year at the earliest.

Then there’s the question of wages, unemployment, consumer demand, savings, and profit margins getting to a sustainable place. And how much does that matter for inflation? And how much does the Fed matter? It’s time to be patient. The Fed’s done a lot, and it could always do more. This year, the big question for the Fed is not a “soft” or “hard” landing; it’s where we are once the dust settles.

The Fed’s framework on inflation has many parts.

The Fed’s “credibility” comes up time and again to justify its big rate hikes. After four percentage points within nine months last year, We get it, the Fed is serious about fighting inflation, even if it causes a recession.

But credibility as an inflation fighter does not rest solely on a strong commitment to getting inflation down; it also requires the world to think you know what you are doing. What looks like the Fed throwing darts in its communication about inflation, from shifting its emphasis from “supply chains” to “too hot labor market” to “de-anchored inflation expectations” to “housing costs” to “services ex housing” is not random.

Inflation is complex. Even before the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, the Fed came to accept that even over the medium-term, it was not purely a monetary phenomenon that the Fed controlled. Inflation ran persistently below the Fed’s 2% target for years despite low unemployment and largely stable measures of inflation expectations. That was frustrating and against the standard theory. A newly released staff memo from 2017 lays out a more nuanced way to think about inflation:

Fundamentals that tell us something about the overall economy:

Stable long-run trend, attributed to anchored longer-term inflation expectations.

Resource utilization, unemployment rate and output at levels that are estimated to be sustainable without pushing inflation above or below target.

Supply shocks, including effects of energy and import prices on core inflation.

Non-fundamentals which temporarily affect monthly or even year-over-year inflation:

Changes in nonmarket prices, such as much of medical care, which consumers don’t pay directly, are hard to measure and tell us little about economic activity.

Unusual changes in other relative prices, that are unrelated to overall inflation.

If you look at the evolution of Fedspeak on inflation from the lens of this framework, it’s clear the weights have shifted some as inflation persists. Supply shocks from Covid loomed large in 2021 when inflation was primarily concentrated. In 2022 as it spread across categories, labor shortages and wage growth took center stage.

The fear of inflation expectations becoming de-anchored and settling above 2% is an ongoing concern at the Fed. Survey- and market-based measures of longer-run inflation that are relatively stable are not enough, especially as inflation persists. Why? The Fed, or at least its staff, is more agnostic about what drives the underlying trend in inflation. They let the data speak using a wide range of statistical models.

The staff’s underlying inflation assumption is informed by considering the long-term trend rate of inflation that is implied by a range of univariate and multivariate time-series models, together with the long-run level of inflation implied by Phillips curve models that condition on measures of expected inflation from surveys or financial markets …

Although the time-series models do not provide a structural characterization of trend inflation, the fact that both survey measures of longer-term expected inflation and the trend estimates from several time-series models have been relatively stable since the late 1990s provides some (admittedly circumstantial) evidence that the two phenomena are related, with inflation’s long-term trend ultimately determined by longer-term expectations.

And so the longer inflation stays high, the more that statistical trend drifts up. It was important for forecasting low inflation before Covid, and it’s also part of the Fed’s thinking now that it’s high. It makes sense that the Fed worries about what it does not fully understand. And it makes sense why the Fed won’t be willing to ease up until several months of lower inflation start pulling the trend estimates back down.

In closing.

Take the Fed at its word.

After two years of being repeatedly surprised by higher-than-expected inflation, it will take several months of sustained improvement to convince them to cut rates. It will take more time than this year. Some of the near-term relief from inflation will likely be temporary, and that’s not good enough. The Fed wants sustainable 2% inflation. Until it is convinced, don’t expect the Fed to blink. Keep your eyes on the economy.

Thank you again for your financial support of my Substack. Please send me questions or ideas for future posts. It’s important to me that you get your money’s worth.

A massive disruption in U.S. financial markets is the only scenario in which I could see the Fed cutting rates this year, and despite the saber rattling, my baseline is that cooler heads prevail. Sooner rather than later would be nice.

Nice work, Claudia. I found this snippet especially compelling coming from someone who understands the mindset within the Fed....:”The Fed is determined not to be head-faked again. It won’t cut until it’s confident about the lower inflation. That level of confidence is unlikely this year. If a recession comes or the market slides further, don’t expect the Fed to come to the rescue”. This seems entirely plausible, although it’s not what our financial markets are expecting.

The funds rate has already been above the 10-year bond yield for a while, even before an expected hike.

Such inversion has never been sustained for long without recession.

And we have never had recessions without deep and long rate cuts.

In Feb 2008, the FOMC finally cut the funds rate to 3% - ending the inversion, then steepening the curve.

There would not have been a "great" recession and might have been a soft landing had they done that six or seven months sooner.

https://pbs.twimg.com/media/FnVB10tXoAEt80y?format=png&name=large