Will the real Larry Summers please stand up?

Throughout his career, Larry Summers has been a leader in macroeconomics, holding powerful positions in academia and policy. He advances "Big Ideas" but then often turns 180 degrees. Why is that?

As a student and practitioner in macroeconomics, my frustration with the field reached a boiling point during the Covid economic crisis. A journalist friend recently asked me why I get so angry with Larry Summers? Largely, it’s because in my mind, he’s the ‘poster child’ for my frustrations. But there’s more to unpack.

This post is not an attack on Larry. I am asking an honest question about his thinking. I learn from his work and am baffled when he pivots. Why all the twists and turns? Yes, the world changes fast, and his shifts undoubtedly makes perfect sense to him. It would help me and likely others for him to explain why he’s changed his mind.

Source: New York Times. June 25, 2021.

It’s complicated for me and goes way back

I finished my PhD in economics in 2007 with a focus in macro. Before that I worked as a research assistant at Brookings. For more than two decades, I have followed Larry Summers, along with other academics who have also served in top policy roles, including Janet Yellen, Greg Mankiw, Christy Romer, Olivier Blanchard, and Ben Bernanke. During my years at the Fed and White House, I worked for several leading lights, even Stan Fischer whose students are everywhere in macro policy.

But, Larry is special. He was the first economist I ever heard about. My dad, a farmer in Indiana and avid reader of the Wall Street Journal, strongly disagreed in the 1990s with Robert Rubin and Larry’s deregulation of the financial industry. Dad was right.

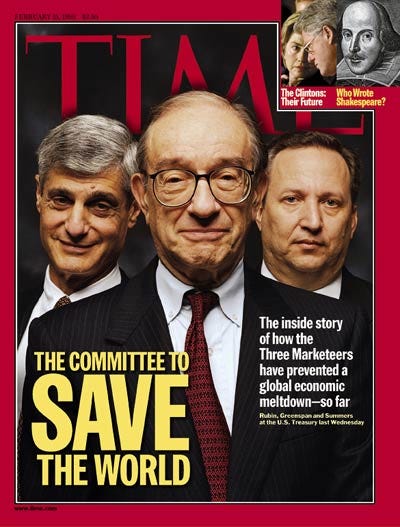

Source: Time Magazine. February 15, 1999.

Now this post is not about Larry’s role in economic policy. The interview with Noah Smith gives his side of the story. What I want to talk about are Larry’s four “Big Ideas” during the past decade: secular stagnation, worker bargaining power, inflation targeting, and most recently, inflation risks.

Secular Stagnation

Since 2016 up until the pandemic, Larry brought “secular stagnation” back. It was an old idea, dating to Alvin Hansen in 1939. Larry developed it within the context of the low inflation and low interest rates after the Great Recession. Here’s his paper with Lukasz Rachel in 2019, “On Secular Stagnation in the Industrialized World,”

We argue that the economy of the industrialized world, taken as a whole, is currently—and for the foreseeable future will remain—highly prone to secular stagnation … We show, using standard econometric procedures and looking at direct market indicators of prospective real rates, that neutral real interest rates have declined by at least 300 basis points over the last generation. We argue that these secular movements are in larger part a reflection of changes in saving and investment propensities rather than the safety and liquidity properties of Treasury instruments … Our diagnosis necessitates radical revisions in the conventional wisdom about monetary policy frameworks, the role of fiscal policy in macroeconomic stabilization, and the appropriate level of budget deficits, as well as social insurance and regulatory policies. To that end, much more of creative economic research is required on the causes, consequences, and policy implications of the pervasive private sector excess saving problem.

During the Covid crisis, policymakers in the United States got “radical.” The Fed is pursuing a new framework and Congress enacted nearly $5 trillion in fiscal relief. Yes, inflation stepped up, so did consumer spending. People got a lot more stuff this year. In fact, consumer spending, adjusted for inflation, is rising at twice the pace (black dots) this year as in 2019. Good, right?

In January 2020, at the economics annual meetings—right before the pandemic hit—I heard Larry Summers declare that “my hypothesis [about secular stagnation] is more correct now than when I proposed it in 2013.” A year later, he called the $2 trillion American Rescue Plan “the least responsible fiscal macroeconomic policy we’ve have had for the last 40 years” and said there was “no good economic argument” for putting money people’s pockets with stimulus checks. So how did Covid—the deepest recession since the Great Depression—reverse his call to support more demand?

Worker bargaining power

Another idea that Larry, among others, pushed is that the decades-long decline in worker bargaining power was hurting the economy. Here’s his research in 2020 with Anna Stansbury, “The Declining Worker Power Hypothesis: An Explanation for the Recent Evolution of the American Economy,”

Rising profitability and market valuations of US businesses, sluggish wage growth and a declining labor share of income, and reduced unemployment and inflation have defined the macroeconomic environment of the last generation. This paper offers a unified explanation for these phenomena based on reduced worker power. Using individual, industry, and state-level data, we demonstrate that measures of reduced worker power are associated with lower wage levels, higher profit shares, and reductions in measures of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). We argue that the declining worker power hypothesis is more compelling as an explanation for observed changes than increases in firms’ market power, both because it can simultaneously explain a falling labor share and a reduced NAIRU and because it is more directly supported by the data.

The reduction in worker bargaining power, sometimes caused monopsonies—where employers have the upper hand in a labor market—experienced a rebirth during the past decade. The idea goes back at least to Joan Robinson in 1932 and more research spurred by the decline of unions in the United States and sluggish wage growth.

Fast forward to 2021 and hand wringing over labor shortages. Finally, some low-wage service workers got bargaining power, with reports of signing bonuses and higher wages. But again, Larry turned this development into a problem and used it to buttress his case that inflation was getting out of hand.

Inflation targeting

Speaking of higher inflation, before Covid, Larry along with Olivier Blanchard and macroeconomists urged the Fed to raise its inflation target to 3% to 4%. Joseph Gagnon summarizes the debate well. Note, it coincided with the Fed’s framework review which drew on external economists too. Here’s Larry at a Brookings event in 2018, “Should the Fed stick with the 2 percent inflation target or rethink it?” :

My conclusion, therefore, is that we are living [in 2018] in our current framework in a singularly brittle context in which we do not have a basis for assuming that monetary policy will be able, as rapidly as possible, to lift us out of the next recession and, therefore, that a criterion for choosing a monetary framework, when we next choose a framework, should be that it is a framework that contemplates enough room to respond to a recession. Meaning, nominal interest rates in the range of 5 percent in normal times. Whether that is achieved through changing conventions on how one permits above target inflation, providing for adjustment to changes in -- based on the price level rather than the rate of inflation or whether that is done in the context of relying on nominal GDP seems to me to be a question of second order importance. What is of primary importance is that we establish a framework in which our best guess is that we will have room rather than that we won't have room to respond to the next recession. And so, I would suggest, as a design criterion, that an appropriate framework allows for a 5 percent nominal interest rate in normal times.

12-month change in prices (excluding food and energy) has settled at about 3.6%. And 10-year Treasury rates are 1.4%. Larry got what he wanted, albeit in abnormal times.

Inflation risks

Fast forward to the Larry Summers of today. He is using his every platform, which are as high profile as they are numerous, to argue that inflation is spiraling out of control. To put it mildly, in the context of his research right before the pandemic, it’s been a wild ride to follow his arguments and rhetoric. This is from Larry’s opinion piece in August 2021 at the Washington Post:

The idea behind quantitative easing is to lower medium- and longer-term interest rates and increase asset prices so that the private sector will spend more. Why is this still a sensible objective when job openings are at a record high, inflation is running well above the Fed’s target … And how high-quality can investment be if it would not have happened with a 1.7 percent 10-year rate and will now occur because of even lower rates?

In a rhetorical ‘flourish,’ Larry compares the Fed’s current approach to monetary policy to the United States’ failed wars in Afghanistan and Vietnam. Sigh.

To be fair, macroeconomics is hard. Policymakers look to us to answer impossible questions. Covid made the impossible downright absurd. No one can prove they are right, and so not surprisingly, tempers are short. My post is an attempt to step back and set our past year and half within the context of the decade before it. Larry is a prominent macroeconomist, so his ideas are a good way to frame that conversation.

Wrapping

Whether you agree with Larry Summers or not, he is one of the big thinkers in macro. His arguments on secular stagnation, worker bargaining power, inflation targeting, and inflationary risks are four recent ones. Larry’s platforms are huge in academia, policy, Wall Street, and the press. As a result, it would be useful for him to explain the shifts in his thinking. Some compassion for those trying to keep up would be nice too.

PS The “Inspiring Quotes” in my inbox today speaks to creative thinking and change.

So, maybe the answer is simply that Larry’s head is round.

Please consider financially supporting my Substack with a paid subscription. You will help me to write regularly about economic policy. You will also receive some paid-subscriber-only posts.

First of all, I really agree that Summers does not explain his policy recommendations well. We all deserve better. That said:

Summer’s turn (?) on secular stagnation. I can think of at least two reasons. 1) The Fed had already changed course, abandoned inflation ceiling policy so no “stimulus” (as opposed to “relief”) was necessary. 2) His policies for secular stagnation were to alleviate inadequate demand and he saw the COVID recession as mainly a problem of supply.

Bargaining Power again two 1) He favored structural chances to increase labor’s bargain power like unionization (?) what he was seeing was cyclical. 2) The increases were driven by supply constraints (unemployment benefits(?) or workers fear of returning to still COVID-ridden workplaces.

Inflation targeting: Maybe he thinks that we do not need a higher inflation target now that the Fed has shown that it can achieve its 2% target by showing markets that it really MEANS 2% as an average, not 2* as a ceiling. As for QE in October 2021, maybe he thinks that the Fed has won, markets believe the Fed will achieve its 2% target and does not need to continue with QE at present levels.

Inflation risks: Maybe he is afraid the Fed will get cold feet about bringing inflation expectation back in line if they stay to far above target too long.

But again, I wish he would make his political/economic arguments clearer.

Whenever I try to understand Summers I think about the fact that he approached both Elizabeth Warren and Yanis Varoufakis with the following pitch:

“Larry leaned back in his chair and offered me some advice,” Ms. Warren writes. “I had a choice. I could be an insider or I could be an outsider. Outsiders can say whatever they want. But people on the inside don’t listen to them. Insiders, however, get lots of access and a chance to push their ideas. People — powerful people — listen to what they have to say. But insiders also understand one unbreakable rule: They don’t criticize other insiders." https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/27/business/from-outside-or-inside-the-deck-looks-stacked.html

Larry Summers said to Yannis Varoufakis: “ ‘There are two kinds of politicians,’ he said: ‘insiders and outsiders. The outsiders prioritize their freedom to speak their version of the truth. The price of their freedom is that they are ignored by the insiders, who make the important decisions. The insiders, for their part, follow a sacrosanct rule: never turn against other insiders and never talk to outsiders about what insiders say or do. Their reward? Access to inside information and a chance, though no guarantee, of influencing powerful people and outcomes.’” Source: Yanis Varoufakis’ book, “Adults in the Room.”

So... take anything Summers says with a grain of salt. You are an outsider and he's not telling you what he really thinks.