Who should get a $1,400 check?

Everyone who got a check last time should get one now. #StimulusChecks2000

Summary: Over a decade of high-quality research shows that about one half to two thirds of the stimulus checks is spent within a few months. Money in the bank, not family income, is the most reliable predictor of who will spend and who will save. But we don’t know people’s bank account balances. From surveys, we do know that half of U.S. families lost income since the crisis began, but we do not know exactly who did in the population. Simply put, the government does not know who needs the check most and who is most likely to spend it. Without that information, lowering the income threshold for the $1,400 check from $75,000 to $50,000 per adult would cut out 40 million people, millions of whom need it and would spend it. The recent policy debate about “targeting” the checks to lower incomes has overemphasized the splashy new findings from Opportunity Insights. I explain here why that’s a mistake.

In that new analysis of the recent $600 stimulus check, Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Michael Stepner at Opportunity Insights, argued,

“households earning more than $78,000 will spend only $105 of the $1,400 stimulus check they receive …. targeting the next round of stimulus payments toward lower-income households would save substantial resources that could be used to support other programs, with minimal impact on economic activity.”

Raj and his team’s analysis landed — with glowing news coverage in the Washington Post on January 26—in a live debate about President Biden’s proposal for $1.9 trillion in relief. Republicans argue that’s too big and too soon after the $900 billion package from December. Their counterproposal includes more “targeted” checks, which lower the income threshold for a $1,4000 check to $50,000 from $75,000 per adult. Any nod to bi-partisanship would require Democrats to cut the total price tag, including the checks. In Biden’s proposal, the checks (including partial ones) would cost $464 billion—about one quarter of the total cost.

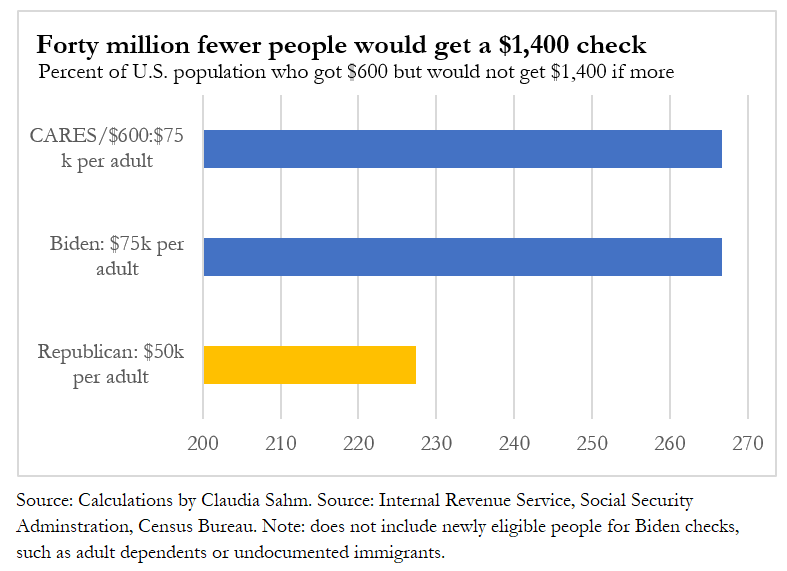

More targeted checks, by my estimate, would mean that 40 million fewer people (12% of the population) who got a $600 check would not get a $1,400 check. That’s like Kyle Pomerleau’s estimate of 46 million (14% of the population).

Giving checks to fewer families is exactly what Raj and his team told us would be better policy. It seems like a win-win for policy makers, smaller price tag and evidence saying those families didn’t need it. Last week the White House got on board with the more targeted checks. However, a potential issue with the compromise is that $1,400 checks are broadly popular: eight in ten Americans are in favor of them.

I am deeply dismayed that the White House seemingly used the new, unvetted study from Opportunity Insights to justify a policy change that would adversely affect so many Americans. With over a decade of experience at the Federal Reserve and a year at the Council of Economic Advisers, I passionately believe that one paper alone should not have such a big effect on policymaking. In addition, as a researcher in this area, I view the precise income cutoff that Raj and his team argue for as being at odds with over a decade of peer-reviewed research, including my own, and unsupported by the underlying data that they used for their analysis.

So that’s why my reaction was so strong and why I got heated about their analysis on Twitter. Now, if you had come to me and said, “To be bipartisan, we must reduce the number of people getting a $1,400 check, so we can reduce the price tag of the relief package. Who should we leave out? I would answer, “Those with the highest income who got the $600 check.” That’s me being pragmatic. If you then asked me, “Should we use Raj’s analysis to justify the change?” I would say, “absolutely not.” I am writing this post to explain why not. I will get a little weedy, but the weeds matter. Those 40 million people who wouldn’t get $1,400, they matter even more.

Raj Chetty is a highly regarded Harvard economist. Every analysis from him and his team is a news event. I do not bring those credentials, but I do bring two things they don't: Over a decade at the Federal Reserve helping estimate the spending effects of the 2008 rebates, the 2009-10 Making Work Pay tax credit, and the 2011-12 payroll tax cut. I also researched those programs, along with the $2,000 CARES checks, with Matthew Shapiro and Joel Slemrod at the University of Michigan. To give both policy advice and do my research, I had to know the findings of the other papers on the topic inside and out, as well as know which data to trust.

To be fair, Raj and his team are not the only economists who think big checks are bad idea. Larry Summers said recently, “There is no good economic argument for the $2,000 check.” Others like Jonathan Parker—an expert on stimulus checks—agrees with Raj that higher-income families should not get the check. But he’s not saying it’s because they will spend less; it’s because they are less in need. To him, the checks are “relief” not “stimulus.” I disagree. It’s always both in a recession; Covid is not different in that regard. If you can’t pay your bills, a check allows you to spend more than you could in a world without a check. That’s stimulus and relief. We are down 10 million jobs relative to before the crisis. As vaccinations progress and daily life returns, our economy will need some oomph to get those jobs back and people back to work.

A key difference between the Covid recession and all other recessions in living memory is the sheer breadth of the hardship. Half of households lost income in 2020, according to the Census Bureau, but less than 20 percent got jobless benefits. My recent Bloomberg Opinion piece shows that those gaps, while largest for low-income families, are sizeable through families with $75,000 to $150,000 in income. Many of them, if Raj’s thinking prevails, wouldn’t get a check.

To be fair, Jonathan and some others who want more targeted checks understand this reality. He would like eligibility for checks to be based on 2020 income, not 2019 as with the prior two checks. I would love to use 2020 income, but it’s not possible for the IRS to simultaneously get checks out fast and process the hundreds of millions of tax returns they would need to in order to use 2020 income. That 2019 income is all we’ve got is itself a good reason not to lower the income thresholds.

Also 2020 income is not even the best metric of hardship. The decline in income from 2019 to 2020 would be much better, since it’s the shortfall that makes it hard for families to pay their bills. I have not heard anyone suggest that we tie checks to the change in annual income during recessions. Makes sense. It would add another layer of administrative complexity.

I have no idea exactly who are the Americans who lost income last year. No one does. We must base policy on what we know, not what we wish we knew. Lowering the income threshold would miss millions who are suffering and who need that big check.

But let’s get back to the research. Raj’s paper is an outlier in over a decade of research in which income is not a strong predictor of who will spend the checks. Some studies show that lower-income families spend less of their checks, but no one has argued that high-income families spend next to nothing out of their checks, as Raj is suggesting. More commonly, across studies, it’s having little or nothing in your bank account—referred to as “low liquidity”—that’s associated with more spending out of stimulus checks. (Technically, liquidity is any easily accessible resources.)

Lower-income families are not the only ones with no money in the bank—some higher-income families are basically in the same boat. Their big paychecks, for example, go to paying off big mortgages and student loan debts. As Greg Kaplan and Giovanni Violante show, if you give those wealthy ‘hand-to-mouth’ families a check, they will spend too. And this is not a trivial group. They find in another paper with Justin Weidner that one-third of all US families do not have much easily accessible money, of which over two-thirds are indeed wealthy.

So where does the belief, still prominent among DC wonks, that high-income people don’t spend stimulus checks come from? It’s based on much earlier research that examined a related but different question: do the rich save more? Twenty years ago Karen Dynan, Jonathan Skinner, and Stephen Zeldes found that, on average, families with high income save more of their lifetime income than families with low income. Carefully done and totally makes sense. But it tells us little about who would spend a $1,400 stimulus check during a recession. It’s not the same conceptually or contextually. Sadly, it’s often cited as the basis of the belief that it’s best to target checks to low-income people.

Dozens of research teams using different data and different methods (a requirement for evidence-based policy advice) have studied what people did with their 2001, 2008, and 2020 checks in the United States, as well as stimulus programs in countries from Australia to Israel. Some papers do find lower income families spend more than higher-income families, but the result is not consistent across studies and is often to be imprecisely estimated. In contrast, the role of low liquidity (and related preferences) in spending appears across multiple studies.

As one example of the imprecise and unreliable effects by income, Jonathan Parker, Nick Souleles, David Johnson, and Mark McClelland find that both the bottom third and the top third of families by income spent about 20% of their stimulus checks in 2008 on nondurable goods within three months. When they include durable goods like cars and services, the lowest income households spent 128% of their checks and the highest income 77%. All, but the 128% estimate, are not statistically distinguishable from zero. Moreover, none of the point estimates suggest high-income families spend nothing. The data are simply too noisy to say how income relates to spending out of the checks.

In an earlier study of the 2001 checks, they found that both bottom third of families by income and the top third spent more on nondurables than the middle third, but again, only the spending of low-income households is precisely estimated. (See bottom panel of Table 6.)

Likewise, my research with Matthew Shapiro and Joel Slemrod on the 2008 and 2020 checks shows no clear pattern in spending by income. Same as in Matthew and Joel’s study of the 2001 checks. Our methods are notably different than Jonathan and team’s—they use the Consumer Expenditures Survey (CES) in which people report their spending every month. To estimate how much of the checks get spent, they use the receipt of the checks, which was randomized in 2001 and 2008 due to administrative constraints at the IRS. We use the Michigan Survey of Consumers in which people tell us directly what they “mostly” did with their checks. While quite different, the two approaches largely identify the same families as spending most of their checks. Jonathan and Nick showed a correlation between the two types of questions on the CES in 2008.

Now let’s bring in yet another group of researchers. Like Raj and his team, they use data constructed from a private company. Unlike Raj, their data from JPMorgan Chase Institute has been used in peer-reviewed research and refined over six years. In their study of the CARES Act checks, Natalie Cox, Peter Ganong, Pascal Noel, Joseph Vavra, Arlene Wong, Diana Farrell, and Fiona Greig found that the level of spending (Figure 5, panel B), among the bottom 75% of families by income jumped as soon as checks start to arrive. The increase among the top 25% is smaller. Note, when trying to estimate how much of the rebates are spent—that is, how large the boost to aggregate spending is, we must use changes in the levels, not the percent changes. And recall, that only the top 80% by income got the full stimulus checks in CARES, so it’s not surprising that the spending of the top 25% doesn’t change much when checks began to arrive.

And this just scratches the surface on all the research about stimulus checks. In my policy proposal to make checks automatic, I summarize the findings from 2001 and 2008 checks. (See page 72-74). Last fall, Mike Garvey and I wrote a summary of the studies by then about the CARES checks. Stimulus checks are good policy in a recession. They get relief to families—who can choose whether it’s best for them to spend, save, or pay off debt—and because many dollars from the checks are spent, it’s an effective way to get the economy going again. It worked in 2020 as it did in the past. The lockdowns and restrictions on face-to-face interactions did not reduce spending out of the checks. In this one regard, the Covid recession was not different.

Sometimes a new paper comes along that should change our thinking. Raj and team’s new analysis is not one of those. Here are three of its big problems. First, and most important, their data and methods do not support their precise claim that families with income over $78,000 will not spend the checks. They ignore the uncertainty from measurement error. Regression analysis, as they use, always provides estimates with a range around them in which the ‘truth’ lies. And the Opportunity Insights data, by construction, have a lot of measurement error.

Their data on income starts with zip-code level median family income in the American Community Survey (ACS) from the Census Bureau. (I went to the appendix of the appendix of their analysis to understand the data). The Census Bureau makes clear that the estimates from the ACS, especially at smaller geographies like zip codes, have large sampling errors. Moreover, “Sampling errors [in the ACS] must be reported as margins of error, because the variability of the estimates is increased with smaller sample sizes. In some cases, the sampling error can exceed the estimate.” It’s not a problem with the Census survey. It’s because the survey’s estimates are from a sample of families, not all families in the United States.

Taken together, the standard errors and the sampling errors, do not support the precision in their claim about the income cutoff. They do not report or even acknowledge the uncertainty in their estimates in the one-page policy brief. Then they use their estimates to claim it’s a waste of resources to send money to families making precisely over than $78,000.

Second, they are giving advice about which families by income should get checks, even though they are not analyzing data on families. They have zip-code-level median income. In addition, they do not consider geographic differences in the cost of living. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics tell us these are substantial. For example, $78,000 of income, adjusted for regional price differences, is worth only $61,000 in New York but over $84,000 in Mississippi.

Lowering the income threshold for the $1,400 checks will exclude families in places with a high cost of living, places like New York City and Los Angeles which have also been hotspots of Covid deaths and job losses. The 40 million people to whom Raj and team say we should not give checks are not spread out evenly across the country. Thus, the lower income thresholds would hurt some parts of the country more than others. A national crisis requires national relief.

Finally, the analysis from Raj and team has not been reviewed by other experts. The results on the 2001 and 2008 stimulus checks that I discussed above have been peer reviewed and are published in top economics journals. I am an expert, and I have a long list of other technical concerns about their analysis. I am disappointed that the Council of Economic Advisers—the group of economic experts at the White House who advise the President—apparently did not carefully review Raj and team’s analysis.

Anyone who knows micro data should have seen many red flags on even a quick read of their one pager. Anyone who read their appendices would many more. Ask any expert in the area (and I have asked others), and they would tell you that Raj and team’s analysis was not ready for prime time. Where was the pushback at CEA? Maybe there was some in private, but with so much public attention given to the paper and Biden’s subsequent openness to lowering the income thresholds, Jared Bernstein and Heather Boushey, the two members at CEA, should have been publicly critical of Raj and team’s claims. They should have made clear that it was the total price tag of the relief package not that one study which was shifting their views on the checks.

Tying it all together, a $1,400 check should go to everyone who got a $600 check. Many economic arguments exist for the checks. President Biden should keep his promise to the millions of Americans who have endured the worst crisis in generations.

I see nobody here, or in congress, pays 1 thought to the homeless.

I was homeless, as a disabled veteran when the pandemic hit. This eviction moratorium has not helped, & has instead hurt our homeless population. The stimulus, or relief money, has helped, but it's paltry.

None of you give me a bit of hope.

How kind of you to attribute a poorly constructed study intentionally studying the wrong population to make an unwarranted conclusion to a good faith mistake. I'm also sure that the newspaper owned by the world's richest person using that paper to brow beat congress was also just a little oopsie. Or we could just be honest and admit that there is broad bipartisan agreement in congress and in elite circles all over this country in favor of murdering as many poor people as humanly possible.