Unemployment affects everybody too

Inflation is high, and unemployment is low. What does that mean for Americans? If you listen to the talking heads, you’d think it’s all about inflation. But that's wrong.

Here’s former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke on why inflation is a broader concern than unemployment:

The difference between inflation and unemployment is that inflation affects just everybody. Unemployment affects some people a lot, but most people don’t respond too much to unemployment because they’re not personally unemployed. Inflation has a social-wide kind of impact.

I strongly disagree. Both inflation and unemployment have “social-wide” effects.

Low unemployment is good for all workers today

First, Bernanke is thinking too narrowly.

Unemployment is currently 3.6% which is very close to its fifty-year low. Yes, the difference between a 6.4% unemployment rate, as it was in January 2021, and 3.6% now is only 4.6 million more workers out of a labor force of 164 million. But far more workers benefit. The low unemployment rate is a sign of a strong labor market. A strong labor market is good for all workers.

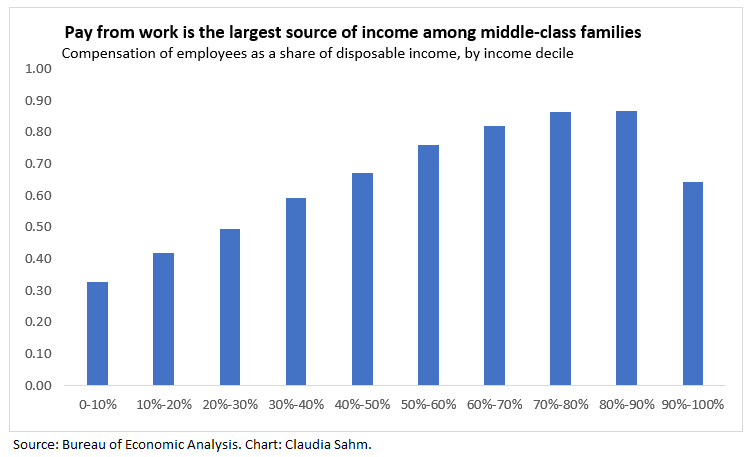

Compensation from work is the key source of income, especially among middle-class families. It is less important among those with the highest income or among retirees. Anything that boosts employment and take-home pay is good for most Americans.

A strong labor market gives workers bargaining power. Often that good news for workers is framed as bad news for the economy. The high rate of workers quitting and moving to better jobs is described as a sign of “overheating,” since companies must increase pay to hire. Even if wage gains aren’t keeping up with inflation, higher base pay matters. More money is good for workers and their families.

A strong labor market does more than boost wages. It creates better jobs. One sign now is that the number of full-time workers is at an all-time high.

It’s part-time employment that’s lagged. That’s good for workers. Many of these are bad jobs. Not knowing how many hours you will get means you don’t know your pay; not knowing when you will get those hours means you have less control over your life.

Plus, full-time hours mean more pay. The wage rate is essential, and so are hours.

The reality was very different after the Great Recession. The labor market recovery was very slow, and it was part-time, not full-time, jobs that led the way.

Low unemployment is good for workers in the future.

Second, Bernanke is thinking too short-term.

The effects of a strong labor market last for years. Several researchers have shown that the weak labor market after the Great Recession negatively affected the careers of individuals. For example, focusing on young adults who entered the labor market during the Great Recession, Jesse Rothstein found adverse effects on these workers’ careers for the next decade:

I study cohort patterns in the labor market outcomes of recent college graduates, examining changes surrounding the Great Recession. Recession entrants have lower wages and employment than those of earlier cohorts; more recent cohorts’ employment is even lower, but the newest entrants’ wages have risen. I relate these changes to "scarring" effects of initial conditions. I demonstrate that adverse early conditions permanently reduce new entrants’ employment probabilities. I also replicate earlier results of medium-term scarring effects on wages that fade out by the early 30s. But scarring cannot account for the employment collapse for recent cohorts …

In another study, Dirk Krueger, Kurt Mitman, and Fabrizio Perri estimate large reductions in well-being from the Great Recession, and these effects are largest for households with low wealth:

How big are the welfare losses from severe economic downturns, such as the U.S. Great Recession? … We find that the welfare cost of losing one's job in a severe recession ranges from 2% of lifetime consumption for the wealthiest households to 5% for low-wealth households. The cost increases to approximately 8% for low-wealth households if unemployment insurance benefits are cut from 50% to 10%. The fact that welfare losses fall with wealth, and that in our model (as in the data) a large fraction of households has very low wealth, implies that the impact of a severe recession, once aggregated across all households, is very significant (2.2% of lifetime consumption). …

The long-term effects in both studies are not limited to the unemployed. A strong labor market is beneficial to many workers. And it’s beneficial for years into the future. It is worth noting that some of the inflation, such as vehicle prices and energy, are likely to reverse. So, in the years to come, low unemployment now may matter substantially more than the high inflation.

It is important to note that low unemployment now does have some downsides. Frontline workers, who cannot work from home, have been exposed to Covid throughout, often without protective gear or sick leave. The early expiration of jobless benefit last summer in many states likely pushed some back to work prematurely. Finally, the end of relief, high inflation, and the Fed raising interest rates will push some to re-enter the workforce, like those who are ‘unretiring.’

Even with these caveats, the benefits of a strong labor market are many.

High inflation does not affect everybody the same.

Third, Bernanke is missing some nuance.

He says, “inflation affects just everybody … Inflation has a social-wide kind of impact.” I agree inflation touches everybody, though not to the same extent.

Some of the differences in the effects come from differences in what we buy. For example, if you did not buy a used car last year, your inflation is likely below 8 percent. Some prices like gasoline, food, and housing are a more shared experience.

Then there are the differences in family finances. The talking point that inflation hurts lower-income families the most is missing a critical effect of inflation. We cannot say anything definitive with just information on the income and spending of households. We need to know the entire balance sheet, how much debt, and how much savings. Inflation is a transfer from savers to debtors.

Matthias Doepke and Martin Schneider discuss this point:

This study quantitatively assesses the effects of inflation through changes in the value of nominal assets. It documents nominal asset positions in the United States across sectors and groups of households and estimates the wealth redistribution caused by a moderate inflation episode. The main losers from inflation are rich, old households, the major bondholders in the economy. The main winners are young, middle-class households with fixed-rate mortgage debt. Besides transferring resources from the old to the young, inflation is a boon for the government and a tax on foreigners. Lately, the amount of U.S. nominal assets held by foreigners has grown dramatically, increasing the potential for a large inflation-induced wealth transfer from foreigners to domestic households.

Guess who has a lot of savings? The very wealthy. Who has debt? The rest of us.

The transfer to debtors may not be enough to overturn the argument that inflation hurts those with the least the most, but it should be part of the conversation too.

In closing

Our current recovery with low unemployment but high inflation is an incomplete one. The frustration of Americans today is not because they don’t care about low unemployment; it’s because inflation is too high. And that’s fair to be angry.

But, it’s incorrect for talking heads to argue that the recovery is a failure because policymakers did not prioritize low inflation. One could make a case against the recovery from the Great Recession which did not prioitze low unemployment. But it’s not worth arguing over which one was better. It’s time to get this recovery done.

Please consider financially supporting my Substack with a paid subscription. You will help me to write regularly about economic policy. You will also receive some paid-only posts.

Another really first Rate analysis. But don’t be too hard on Ben.

Although the economics clearly show that recession is worse than moderate inflation, Iinflation is a much better story. The media carries it daily, with reporters standing at gas pumps. Everyone who drives or shops at supermarkets has stories to tell about how much it cost them to fill up their tank or to Buy a flower pot or a steak. Few if any of them realize how much they gain from a buoyant economy. All of them know how much they’re losing from inflation. Politicians of course follow the media As well as guide it and are led by Voters fears as well as create them.

Great post. Thank you. I finished grad school, stared my career, and bought a house in the early 80s, when no one would sell to me on the GI Bill & mortgage rates were some 17%. Never missed a meal. If you have a job, you can cope with inflation. Not easily, maybe, but you can do it. Got no job? That's really really tough.