On December 18th, the Fed officials voted to reduce the fund’s rate by 25 basis points, tightened their forward guidance on future cuts, and issued a new Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) with more inflation and fewer cuts expected. When the dust settled after Chair Powell’s press conference, the S&P 500 was down 3%, and 10-year Treasuries were up 10 basis points. These were usually large swings for a Fed Day, especially considering markets were already primed for a “hawkish cut.”

Today’s post argues that a multi-level failure of the Summary of Economic Projections (which includes the dot plot) was partly to blame. People came looking for clarity. They got even more uncertainty and the sense of a Fed ‘flying blind.’

To judge the current state of affairs, it is useful to return to the launch of SEP in 2007. In service to greater transparency, then-Chair Ben Bernanke highlighted the “projections as functioning in three different ways: as a forecast, as a provisional plan, and as an evaluation of certain long-run features of the economy.” Seventeen years later, the December 2024 SEP shows us how far the reality of the SEP is from its ideals—on all three functions.

It falls short as a forecast.

The Summary of Economic Projections is not a forecast. It’s 19 individual forecasts from FOMC participants bundled together. It includes 19 individual views of “appropriate monetary policy.” That’s all clearly explained, except what markets want is the Fed forecast. What is the collective thinking of the Fed on what is most likely to happen in the economy, and how would the Fed likely react? We have settled for a crude approximation of the Fed forecast in the SEP: the median estimates from the Fed officials. The medians probably aren’t even from one official’s forecast, let alone an accurate picture of the Fed forecast.

The multitude of forecasts problem is nothing new, but the SEP broke down spectacularly in December. After several weeks of arguing, “We [the Fed] don't guess, we don't speculate, and we don't assume.” When it comes to the new Administration’s policy, Powell admitted at the December press conference that the SEP played by other rules:

… Some people [in the SEP] did take a very preliminary step and start to incorporate highly conditional estimates of economic effects of policies into their forecast at this meeting and said so in the meeting. Some people said they didn't do so, and some people didn't say whether they did or not. So, we have a people making a bunch of different approaches to that.

So, what exactly are we looking at in the SEP? Did the inflation forecasts revise up in 2025 from carrying forward the unexpected stickiness of late 2024, or is there a temporary increase in inflation from tariffs or additional tax cuts? Or what? Given Powell’s comment at the press conference, it’s impossible even to know if the median official included assumptions about new fiscal policies.

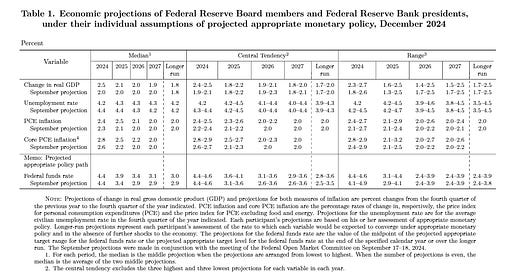

The medians rose such that PCE inflation in 2025 is expected to exceed its level at the end of 2024. The range of inflation forecasts widened from 2.1% to 2.9% in the December forecast from 2.1% to 2.4% in September. It’s hard not to see policy assumptions at work, but we don’t know. We look to Fed officials as skilled in economic forecasting and monetary policy, but there’s no reason to think they are individually good at forecasting fiscal policy. One might argue that Powell’s argument for no fiscal policy assumptions was too strong. Still, the hodgepodge we got of varying policy assumptions across the 19 forecasts is the worst possible outcome. The SEP needlessly interjected uncertainty into the baseline forecasts and made the SEP even more difficult to interpret as a forecast than usual. What was the benefit?

It is too coarse to convey even a provisional plan.

When Bernanke referred to the SEP as offering a “provisional plan,” he knew it was not a promise from the Fed and should not bind its future actions. It was in service to more transparency. Here is an example he gave (in 2007):

To illustrate, consider the question of the length of time over which a central bank should aim to restore price stability following an unwanted increase in inflation. A central bank that places weight on both employment and price stability, like the Federal Reserve, would not attempt to disinflate immediately or establish a fixed time frame for the restoration of price stability. Rather, the optimal expected time required for completing the disinflation would depend on a host of factors, including the size of the initial deviation from price stability, the initial state of the real economy (for example, the level of unemployment), whether the rise in inflation resulted from transitory or more persistent sources, the extent to which inflation expectations are well anchored, and so on. In circumstances in which disinflationary policy is necessary, the extended economic projections would make clear that the Federal Reserve is committed to maintaining price stability, but they would also provide some indications about what the Committee views as the most appropriate pace of disinflation, given the state of the economy and the requirements of the dual mandate.

The SEPs, since inflation surged in 2021, have shown patience among most Fed officials in returning inflation to 2%, but good luck backing out such a nuanced story of what Fed officials are thinking from the public-facing SEP. The forward guidance in the FOMC statements and Chair Powell’s words were a far more useful source than the SEP.

December showed how the “provisional plan” can complicate monetary policy. The September SEP, which comes late in the year, has the appearance of pinning down a plan for rates in the fourth quarter based on the inflation and unemployment projections. It did not go unnoticed at the December press conference that inflation and growth came in higher and unemployment lower than expected, but the Fed cut rates again.

Powell’s explanation:

So, I would say today was a closer call, but we decided it was the right call because we thought it was the best decision to foster achievement of both of our goals, maximum employment, and price stability. We see the risks as two-sided, moving too slowly and needlessly undermine economic activity and the labor market, or move too quickly and needlessly undermine our progress on inflation. [Discussion of the data in support.] … So, I'll just say, so remember that we couple this decision today with the extent and timing language in the postmeeting statement that signals that we are at or near a point at which it will be appropriate to slow the pace of further adjustments.

The minutes and, later, the transcripts will likely show a nuanced debate among the FOMC about their balancing act. It's more nuanced than could ever be gleaned from a few lines of numbers in the SEP.

Finally, tension has been building around the SEP at the Powell Fed. The Fed has long been “data-driven” in its decisions, but the complexities of the post-pandemic economy have led it seemingly to rely on data over forecasts. Powell even admitted as much at the press conference, “I think the actual cuts that we make next year will not be because of anything we wrote down today [in the SEP], we're going to react to data.” That is a sensible statement, but it does question how much markets should react to the SEP as even a rough plan of action.

A false sense of security is worse than no security.

It leaves us in the dark on the “longer run.”

The third role that Bernanke assigned to the SEP was supporting a discussion about the longer run. It's of great importance now as the Fed tries to assess the restrictiveness of monetary policy and what will likely be the terminal level of the federal funds rate. Outside of the data, the Fed officials’ views on the neutral rate (the longer run rate) may be the most important input to monetary policy next year.

Here, the SEP has the potential to shed light on how the Fed is thinking about these structural features of the economy. In the December SEP, the estimates for the longer-run fed funds rate ranged from 2.4% to 3.9%, with 3.0% as the median.

The median estimate of the longer-run fed funds rate has increased by 0.5 percentage point since the pandemic began. However, the SEP does not indicate why. None of the other longer-run variables, such as GDP growth or unemployment, moved in ways that could help explain the rise in the longer-run funds rate. A common explanation for a higher neutral rate could be higher potential output growth, but according to the SEP, Fed officials largely see recent strong growth as temporary.

In closing.

The goal of greater transparency that motivates the Summary of Economic Projections is laudable, but reality is falling short of its promises. The silver lining is that in 2025, the Fed will review its strategic framework. Communication policy is largely expected to receive a critical once-over. The SEP from December 18, 2024, would be a good case study.

My fundamental concern with the SEP is that it is an individual event, whereas monetary policy is a team sport. The SEP must find a way to convey its role as an input in the policy process more clearly and offer more nuanced interpretations. Or the FOMC must craft a consensus SEP. The medians in the SEP are not the Fed forecast and never will be.

The unredacted version of the SEP, which is published after six years with the FOMC meeting transcript, may offer a path forward. In addition to the estimates in the public SEP, there are qualitative statements from Fed officials explaining their forecasts and appropriate monetary policy path. Natural language processing or generative Artificial Intelligence could be used to systematize and summarize these answers for a real-time release. It would also be an avenue for commentary on changes in key variables like the longer-run fed funds rate. The dynamics that policymakers think are at play are more important than the specific estimate. Fed officials benefit from these discussions at the FOMC meeting, but six years is too long to wait for the public.

The SEP’s goals are worthwhile, making its shortcomings all the more frustrating.

I suppose we need to thank you for a clear explanation of the muddy mess the "Fed" has created.

I believe it is time to retire the SEP. The fomc should publish a decision and do their best to summarize their reasoning. A brief summary of the varying views of the committee, along with a brief outlook of the next 6-9 months should suffice. Time to retire long discussions about R* and long run neutral rates. As Keynes said, "In the long run we are all dead".