The Fed is only looking to past inflation, and that's a problem.

Chair Powell has taken March off the table for the first rate cut, implying that the Fed wants at least nine months of good inflation data before even considering cutting. Nothing else matters.

Above the paywall, today's post discusses the Fed’s backward-looking, inflation-only approach. Below the paywall, I discuss the level of the neutral interest rate.

The textbooks tell us that the Fed must look forward when setting the fed funds rate. Why? It takes time for monetary policy to work through the economy. The lags may be short or long, but there are almost certainly lags between changes in the fed funds rate and changes in the economy. The textbooks could be wrong, but the Fed is departing from received wisdom with its current backward-looking inflation-only approach.

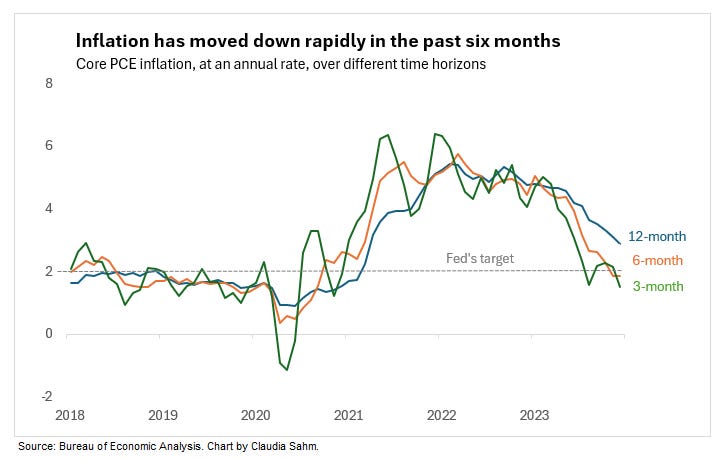

Inflation has come down rapidly in the past six months.

After a two-year slog, inflation really turned the corner last year. The Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) core inflation, which excludes food and energy, was below 3% percent over the twelve months ending in December 2023. It was even below the 2% target in the prior six and three months.

In the Fed’s last forecast, the median Fed official expected core PCE inflation (Q4/Q4) to be 2.4% at the end of 2024. If inflation stays close to its pace over the past several months, it will return more quickly toward the 2% target.

So, the Fed is feeling good and ready to start slowly chipping away at the 5.25% federal funds rate? Nope. Even though the last six months look great—with core inflation coming in at less than 2%—that’s not enough to even start considering cutting.

At the January press conference, Powell laid out the Fed’s thinking:

The lower inflation readings over the second half of last year are welcome, but we will need to see continuing evidence to build confidence that inflation is moving down sustainably toward our goal. Longer-term inflation expectations appear to remain well anchored, as reflected in a broad range of surveys of households, businesses, and forecasters, as well as measures from financial markets

With March off the table, May is the earliest the Fed might cut. That would be nine months of good inflation data. And the public remarks among some officials suggest that the first cut might be later than May.

With inflation down and rates high, the economy is strong.

Growth and the labor market areas where, unlike inflation, the Fed seems willing to rely on its forecast, specifically that the economy will stay strong, regardless of how long they wait or how little they cut. They also worry that solid growth and a good labor market will keep inflation above target, though that didn’t happen last year. The Fed’s record of forecasting in 2023 was abysmal. Here are the median forecasts for growth in 2023 by the date Fed officials made them and the reality:

In March 2023, the Fed’s median forecast of real GDP growth (Q4/Q4) was 0.4% for 2023, and core PCE inflation (Q4/Q4) was 3.6%. The Fed missed on both sides. Actual real GDP growth in 2023 was 3.1%, and core PCE inflation was 3.2%. Growth was more than a percentage point above trend growth, and inflation came down notably.

Likewise, in March 2023, the Fed’s median forecast for the unemployment rate in the fourth quarter of 2023 was 4.2%, and the actual rate was 3.7%. That’s a meaningful difference!

What’s the Fed’s strategy now?

To cling to the backward-looking inflation data.

The Fed’s big misses in 2023 on growth and the labor market came from relying on the logic of the Phillips curve: to get inflation down, demand must come down, too. That proved wrong-headed in 2023. The unwinding of the many disruptions from Covid defied that logic, and 2023 shows it.

The Fed says it has let go of the belief that we need low growth and higher unemployment to get inflation down. Instead, it now argues that the strong economy gives the Fed the “luxury of time” to build “confidence” that inflation will return to and stay at target. As I wrote recently, it’s a risky strategy, and the Fed may overestimate how much time it has.

In closing.

The Fed is data-driven but is taking it to an extreme this time.

Looking for at least nine months of good inflation data before considering a cut is not monetary policy; it’s letting the Bureau of Labor Statistics run the show.

More below the paywall on the neutral federal funds rate: what it is, where it might be now, and why the Fed keeps talking about it. Become a paid subscriber to read more.