Sticky is not stuck: inflation

Inflation. Inflation. Inflation. It's been a rough start to the year on inflation, but it's not all bad news. Most importantly, it shows a path forward if we choose to follow it.

Professional news: I started last week as the Chief Economist for New Century Advisors, an institutional investment management firm in DC. I am very excited about this new opportunity. I will also continue to do some consulting and my writing here.

We now have three months of disappointing inflation to start 2024. My expectation that inflation would keep its solid downward momentum from last year was clearly wrong. I have said all along that it would be a bumpy ride, but the past three months were more like a thump than a bump.

Even so, the bad news is not as bad as the headlines. First, the Fed’s preferred PCE (core) inflation will likely earn a pretty good grade for March, even if the CPI did not. In addition, what’s left in the fight against inflation is far more concentrated than in 2022. Finally, some of what’s being bemoaned as “sticky” inflation by commentators is some inflation settling in at sustainable levels.

Sustainable inflation is what we want.

The Fed's mandate is low inflation and low unemployment. It’s not good enough to hit the goal at one moment in time. On the economy's glide path, inflation settles in sustainably at 2%, and the labor market is sustainably good, too.

The labor market already checks the sustainable box—it’s very good. A solid, balanced labor market is not bad for the Fed—it’s good since that meets half of the Fed’s mandate and gives the Fed some (but not limitless) cushion in waiting to cut rates until inflation is clearly on its way to sustainably to target.

Getting ‘stuck’ at a sustainable level that’s consistent with the 2% PCE target is the thing we want to see. Looking under the hood of inflation—as we always should—we see some good news on this front.

We are finally there with core goods, which exclude food and energy. Core goods inflation spiked in 2022, reflecting supply chain disruptions, a sudden shift to goods from services, and a surge in demand. By the second half of last year, core goods inflation was back to its pre-pandemic levels, bouncing around or below zero.

Of course, it would be nice to have more goods deflation to bring down topline inflation. We may get more, such as from used vehicles, but Covid disruptions to goods have primarily worked their way through the system. Getting Covid disruptions behind us is important.

Some have raised concerns that after good prices had fallen while working out Covid disruptions, their inflation would rise to a higher than pre-pandemic level, reflecting costs of onshoring or friendshoring. That may still be coming, but for now, core goods appear to be in a sustainable, target-consistent place.

Core services remain a problem and even picked back up this year. Even so, there are some encouraging signs (with an important caveat).

There are fewer enemies in the fight against inflation.

In 2022, inflation took off in many goods and services categories. That spreading out of inflation was why the Fed stepped in with aggressive rate hikes. The thinking was that if the Fed ‘cooled’ off the economy—making it harder for people to buy so much—then businesses would stop raising prices. Last year, inflation came down, the economy decidedly did not cool off, and the American consumer kept going strong.

There is no guarantee that we will be so fortunate in 2024. The good news about elevated services inflation is that a much narrower set of categories are the big contributors to the current CPI inflation and even the pickup this year.

Before the pandemic, inflation was close to the Fed’s target. (Note that 2% on PCE is normally more like 2.5% on CPI.) So, a good metric of sustainability is inflation now relative to average inflation before the pandemic or ‘excess inflation.’

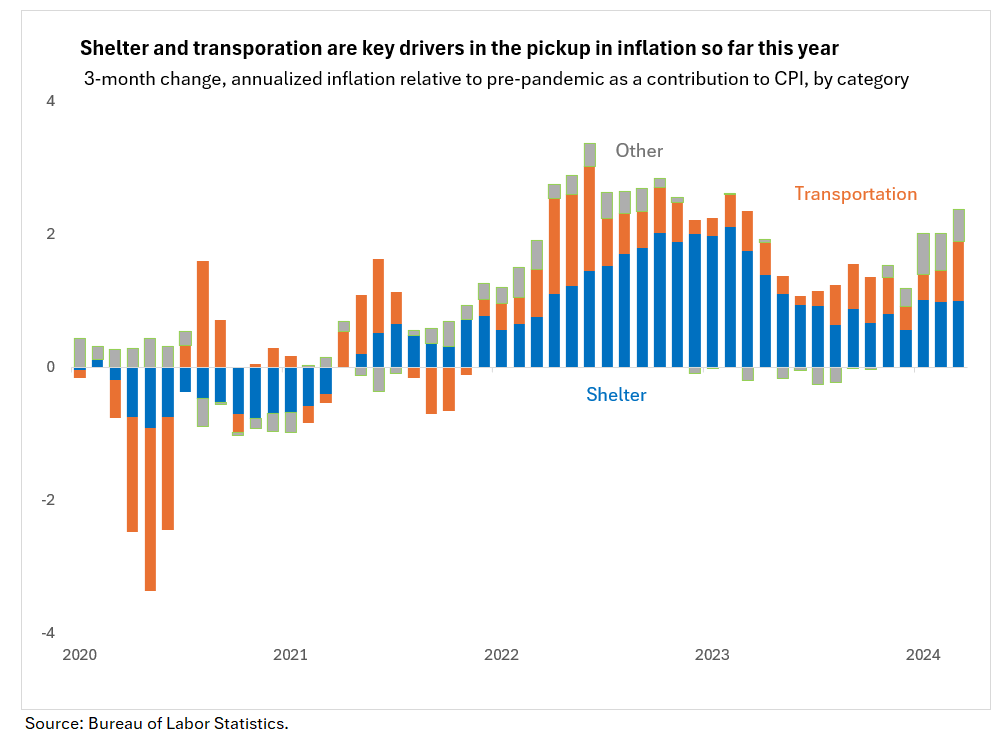

Within core services, excess inflation contributions to CPI are down to a handful of categories. With the year-over-year inflation, the two big contributors are shelter and motor vehicle insurance. The latter's weight in CPI is under 3%, underscoring how massive the price increases for motor vehicle insurance have been.

Again, back in 2022, the excess inflation in the “other” categories, which combines a lot of spending, contributed substantially to high inflation. It’s still there but much more muted. That’s a victory, though it must be sustained.

The big worry about inflation this year is that it picked back up. We closed out last year with considerable optimism, but the first three months of this year took the shine off. However, the pickup, as with the overall level, owes to a narrow set of spending categories. The contribution of excess inflation (3-month change, annualized) in transportation increased notably from December to March. Motor vehicle insurance, repair and maintenance, and airfares were key contributors. Transportation alone explains 70% of the pickup in super core (core services excluding shelter). In overall core services, shelter inflation picked up, too.

The inflation contributions in several other categories in super core have picked up this year, even if they didn’t add up as much toward the topline. It’s important to keep an eye on inflation—regardless of how widespread it is. If nothing else, the first three months slowed the fight against inflation.

Covid’s long and variable lags in the economy.

We may want to shove 2020 down the memory hole, but our economy continues to show echoes of it. Our sectors are deeply intertwined, so a major disruption due to Covid in one sector spread to related ones and takes time to work out.

In the fight against inflation, there’s an ongoing debate about whether the Fed rate hikes act with “long and variable lags.” Maybe. It’s clear that the supply disruptions due to Covid have long and variable lags—and painfully so.

Motor vehicles are a good example of the lags. Early in the pandemic, semiconductor shortages constrained new vehicle production, pushing buyers into the used car markets. As a result, both new and used vehicle prices rose sharply. Subsequently, motor vehicle parts, motor vehicle maintenance, and motor vehicle insurance inflation each picked up. The inflation and disinflation have come almost like waves, with motor vehicle insurance the last yet to crest.

Of course, there are more factors at play than Covid-driven supply shortages. The spike in spending (pent-up demand from Covid and stimulus) early in the recovery put upward pressure on prices, as well as the labor shortages and higher wages. And there are non-Covid changes, too, especially in motor vehicle insurance.

The Fed’s role in fighting supply-driven inflation has been limited. Higher interest rates did not repair global supply chains or attract more people into the workforce. Workers and businesses did the heavy lifting, and it took time. We must grapple with the question of how we can do better the next time we have supply disruptions.

In closing.

To understand inflation, we must examine its key drivers. Identifying shelter and motor vehicle insurance as two primary sources of inflation now is not meant to ‘explain away’ inflation. Inflation is too high; understanding why helps identify the best policy response. Herein lies a bigger problem.

We are down to a few enemies in the fight against inflation. Unfortunately, the Fed’s ‘weapons’ are unsuited to address supply-driven inflation. Sustainability requires getting the excess inflation out of all the spending components. The Fed holding rates or raising them further would eventually put the economy in a recession. That might reduce the demand for other types of spending and bring down their inflation further, achieving the topline inflation of 2%. However, that does not necessarily solve the current problem, and it creates new ones.

Inflation is narrowing down to a few challenging areas. That narrowing reflects several victories in the fight against inflation, but what’s left has a big lesson. It’s time for policymakers outside the Fed to accept responsibility for inflation and, most importantly, do something. The Fed is in the mix, but it can’t fix this alone.

Below the paywall, I discuss why a methodological change in the Michigan Survey will make its inflation expectations less useful to the Fed. Fed watchers should be careful, too.