Lessons from the 1960s for the Fed?

Many economists view the 1960s as a ‘missed opportunity’ to contain rising inflation before it became entrenched in the 1970s. But, it's unclear how much that period should inform Fed policy today.

A pressing policy question is how quickly the Federal Reserve should move to bring inflation down. The late 1960s, when the Fed missed its chance to rein in inflation early, are often pointed to as a reason to act aggressively now.

However, new research by Jeremy Rudd, an economist at the Fed, cautions against drawing parallels with the 1960s since inflation dynamics and the policy environment differed notably.

Note: This post is my reaction to Rudd’s paper and my opinions, not his, on monetary policy.

Source: Getty Images.

Here’s Bill Dudley, former President of the New York Fed, citing the 1960s as he argues that the Fed must raise interest rates aggressively now to rein in inflation:

[If not] Underlying inflation would actually keep rising, driven by higher wages and expectations of more persistent inflation. Ultimately, the Fed would eventually have to step in with even tighter monetary policy than initially contemplated, precipitating a deeper recession.

This is what happened in the late 1960s and 1970s. Inflation wasn’t tackled forcibly early, so it kept ratcheting upward. Eventually, then-Fed Chair Paul Volcker had to force a severe recession to get inflation back under control.

Dudley was correct last year in predicting high inflation now. I was not. And he’s right that the Fed should work to get inflation down now. I agree, but we need to be careful of ‘too slow’ in the past, leading us to go ‘too fast’ now.

So, are the 1960s a valid comparison?

In new research, “The Anatomy of Single-Digit Inflation in the 1960s,” Jeremy Rudd, an economist at the Federal Reserve, argues that largely they are not because inflation dynamics and the policy environment are notably different than today.

The path of inflation

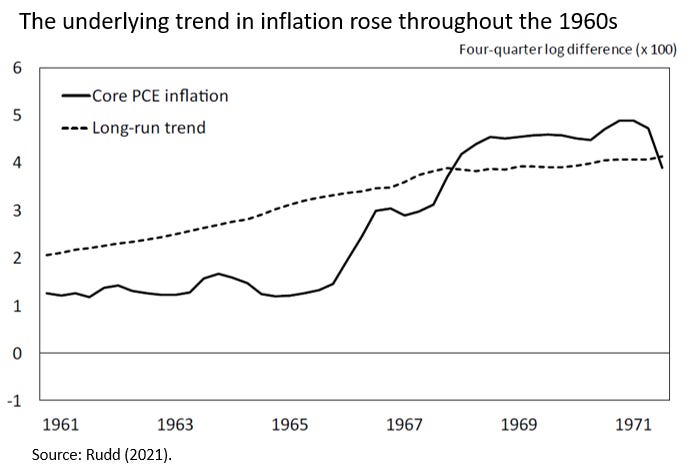

The step-up in inflation was much more gradual in the late 1960s than today.

In 1966, inflation began to pick up slowly, taking about five years to increase three percentage points. During the Covid crisis, a similar-sized increase in core inflation occurred within about one year. The pandemic led to a shutdown of the U.S. economy and caused many disruptions to the supply of goods and workers. That was a more abrupt shock to inflation than the factors behind inflation in the 1960s.

Note well, the Fed today is already reacting aggressively to tame inflation. The Fed is on track to have raised the federal funds rate to 1.75% by late July, up from zero at the start of the year. That’s about one year into the high inflation. So in some sense, the lesson of the 1960s: ‘do not wait long’ is already applied.

Waiting six months to start is not the same as waiting years to get serious about higher inflation. Some people like Dudley believe the Fed should be raising rates even more quickly, but it’s less clear that the 1960s should be our guide on the pace.

As Rudd explains, the Fed is likely not fighting the same inflation dynamics. He estimates the long-run trend in inflation—that is, where inflation would settle if everything else in the economy were normal—was rising for years before actual inflation began to rise in the mid-1960s. Thus, policymakers faced a more formidable challenge of building momentum.

In contrast, before the Covid crisis, underlying inflation appeared stable. In other work, Rudd estimates that before the Covid crisis, the long-run trend in inflation was flat and close to the Fed’s target of 2%. Since the 1990s, the ups and downs in the economy did not affect the trend much. Actual inflation was relatively stable too.

By comparison, the underlying stability before the Covid crisis should make the Fed’s job easier and likely explains why there are few signs of an inflationary mentality.

Of course, a disruptive event like the pandemic could push trend inflation up. Some, like Riccardo Trezzi, former Fed economist, suggest it has. And Dudley is correct that the Fed should not be optimistic about the past trends even if the price pressures from supply chains, labor shortages, and one-time fiscal relief do not persist.

Inflation and the labor market

Another important reason to be wary of drawing lessons from the 1960s is the apparent differences in the relationship between inflation and the labor market.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a wage-price spiral took hold, where higher wages led to higher prices (to cover the costs of higher wages), which then led to higher wages and so on. This dynamic was part of the inflationary mentality that took hold and was a difficult one to break. There’s no evidence of a spiral now, though, at least anecdotally, the first round of higher wages last year leading to higher prices is occurring.

It’s too soon to tell if workers have enough bargaining power to get another round of raises to make up for current high inflation. They might. But after decades of little bargaining power—even when unemployment was low—it’s hard to see how the one-off event of a pandemic could break the trend. The Fed actively trying to push down wage growth, especially if unnecessarily, could cause considerable hardship.

Rudd provides evidence that the Fed should tread carefully here. He estimates that the relationship between the labor market and inflation was much stronger in the 1960s than since the 1990s. (His chart simulates a rise in unemployment and a fall in inflation.) These findings (in other research, too) suggest that a wage-price spiral was not an issue before Covid. High wage growth and high inflation during the Covid recovery are not due to a long-standing relationship but a one-off event.

What’s frustrating is that we do not know precisely why the relationship between inflation and the labor market weakened so much over the decades. As a result, we don’t know what would bring it back. We don’t know if Covid changed anything. Getting this wrong is the biggest risk to people that the Fed faces in doing ‘too little’ or doing ‘too much.’ It is the biggest risk of projecting the 1960s onto today.

Policy environment

Rudd also draws attention to differences in the policy environment in the 1960s and today and the implications for inflation.

First, while fiscal policy likely played a role in the higher inflation in both periods. It would be a mistake to equate the two contributions quantitatively. In the 1960s, the boost from government spending occured throughout the decade, whereas in 2020-21 it was a large one-year burst in fiscal relief. Moreover, the boost during the Covid crisis quickly turned into a drag on GDP growth. The short-term effort to fight the Covid recession and speed the recovery is fundamentally different than the large, new social programs and funding the Vietnam War.

The reversal of fiscal support now is likely to cool demand and lower inflation, maybe more effective than the Fed raising rates. In contrast, in the 1960s, fiscal policy was a persistent factor heating demand, which meant the Fed needed to work even harder.

Finally, a crucial difference was the relationship between the Fed and the White House. The goal of the Fed’s independence was not adhered to as closely then. As one example, during the 1960s, Fed Chair William McChesney Martin worried about the White House's reaction to tightening by the Fed, as Rudd explains.

Martin was also aware that fully squeezing out this “inflationary psychology” would require a long and grueling campaign, one that he did not want to undertake without Administration support.

He therefore gave a speech in May 1969 that suggested such a policy course in the hopes that President Nixon would take up the gauntlet and make a strong public commitment to fighting inflation. Nixon actually did broach the idea of taking “the bad medicine now” with his economic advisers, but was dissuaded by George Shultz, his Secretary of Labor.

That’s a dangerous way to approach monetary policy. And it only got worse in the 1970s. It’s a lot to expect the White House to support slowing the economy and risking a recession. The Fed must do its job regardless. The Fed’s delay in the 1960s came from many missteps. (See Rudd’s paper for more.) Even so, politics is a big one.

Thankfully, politics is a challenge the Fed does not face to the same extent today. The Fed is all in on its independence. Or at least that is its goal. (One could debate how much they achieve it.) But, Powell has what Martin wanted and did not get: buy-in from the President. Biden clearly wants the Fed to bring inflation down now. And while the Fed is trying to do so without an increase in unemployment, everyone knows a recession is possible when the Fed tightens; history says it’s unavoidable.

Wrapping up

Writing ‘the playbook’ in real time is a huge challenge for policymakers, so it is natural to look to the past for lessons to apply. Even so, we must be discerning and try to avoid, as much as possible, ‘fighting the last war.’

The 1960s—when inflation began its upward climb, and the Fed did little to contain it—might suggest that today’s Fed should move aggressively. But, the research by Jeremy Rudd cautions against leaning too hard on the 1960s. The challenges with inflation that the Fed faces now differ in important ways. So might the best policy.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes. Some rhymes just aren’t very good.

Your financial support is valuable and helps me write regularly about economic policy. My goal now is to send at least biweekly posts to paid subscribers, mainly on the Fed. In addition, I am always open to requests or other feedback.

The views in this post are my own and do not represent anyone else.

In the sixties and seventies, as now, the fundamental mistake was to look for domestic policy tools to repair global economic problems -- notably global supply shocks (particularly oil) and unanticipated consequences of driving the dollar down under President Nixon and up under Presidents Reagan and Biden. https://www.aier.org/article/nixonomics-in-retrospect-devaluation-and-wage-price-controls-august-15-1971/

The nature and context of the 60s inflation is completely different! https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/08/25/the-origins-of-the-great-inflation/